In the 18th and 19th centuries, Arctic hunters and early naturalists described a pale, vocal whale that guided people through icy channels—what we now recognize as the beluga.

Those early accounts still matter because the species’ visible quirks—white skin, a bulbous forehead, and an astonishing sound repertoire—tie directly to its role in Arctic food webs and to human cultures along northern coasts. Knowing these traits helps communities manage subsistence harvests, guides researchers monitoring health and population trends, and shapes conservation actions when local groups are in trouble.

Adults typically range about 3–5 meters in length and can live for up to roughly 50 years (see NOAA and IUCN summaries).

Beluga whales combine distinct physical traits, sensory powers, and behavioral adaptations that make them one of the Arctic’s most recognizable and ecologically important marine mammals.

This article examines ten defining characteristics grouped into four areas: physical traits, sensory and communication abilities, ecological adaptations, and human interactions and conservation.

Physical traits

Belugas are visually unmistakable in the Arctic: a stout, rounded body, smooth white skin in adults, a prominent melon, and no tall dorsal fin make them stand out. Those features aren’t just cosmetic—they’re linked to life under seasonal ice and in shallow coastal waters. The thick blubber layer, rounded silhouette, and small dorsal ridge reduce heat loss and ease movement beneath ice floes, while the melon and facial mobility support acoustic foraging and social signaling.

For size context, adults commonly measure about 3–5 meters long and weigh several hundred to over a thousand kilograms, with males typically a bit larger than females (NOAA, Fisheries and Oceans Canada). Museum records and early expedition notes often mention the “white whale” appearance; Inuit hunters and 19th‑century naturalists used skin color and scarring to help identify individuals and age classes in the field.

1. White skin (adult coloration)

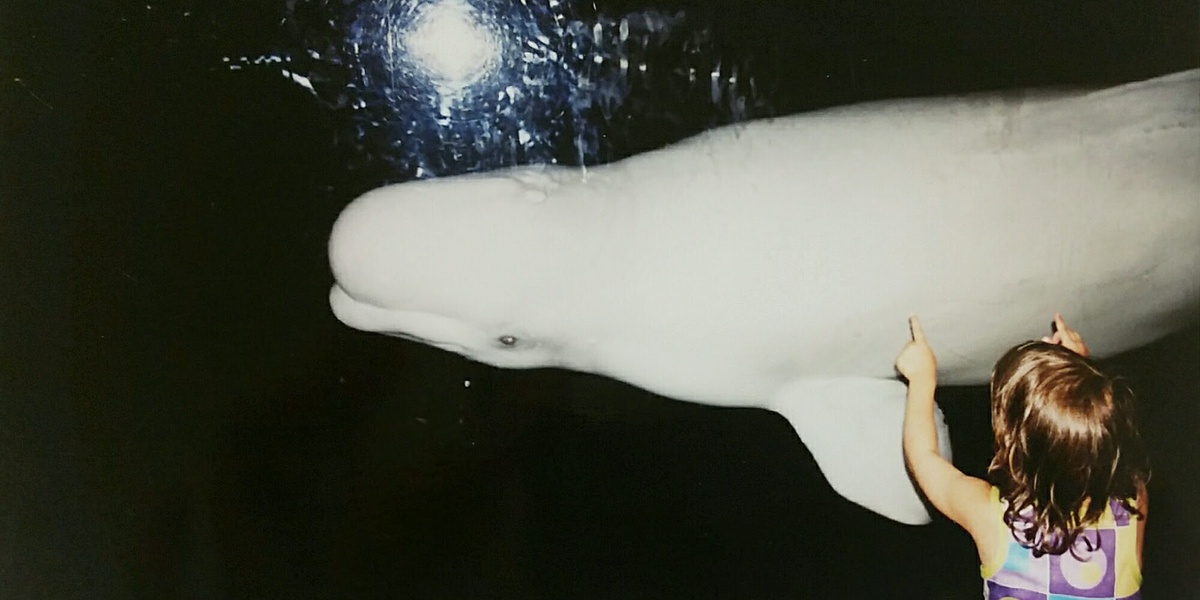

Adult belugas are characteristically white—a key field mark. Calves, by contrast, are born dark gray or brown and lighten gradually over several years, typically passing through a mottled phase before becoming fully white.

That ontogenetic change likely serves multiple purposes: camouflage among ice and snow, and visual signaling within pods. Researchers and Inuit hunters often use skin tone and mottling patterns to estimate age classes during surveys and subsistence activities (field guides and regional studies document the newborn-to‑adult timeline).

2. Size and rounded body shape

Adults typically measure about 3–5 meters in length and can weigh from several hundred kilograms up toward 1,000–1,600 kg in large individuals (verify regional figures with NOAA and IUCN reports).

The stocky, rounded body reduces surface area relative to volume, which helps conserve heat. Size also affects diet and predation risk: larger adults can handle bigger prey and are less vulnerable to orca attacks, while juveniles remain more at risk and often stay in protected nearshore habitats.

3. No dorsal fin and flexible neck

Belugas lack a prominent dorsal fin and instead have a low dorsal ridge. This trait reduces heat loss and makes it easier to travel beneath pack ice without snagging on floes.

Unlike most cetaceans, belugas retain unfused cervical vertebrae that allow notable neck flexibility. That mobility helps them peer into shallow bays, turn their heads to forage along the bottom, and show expressive head movements during social interactions observed in both wild groups and in human care.

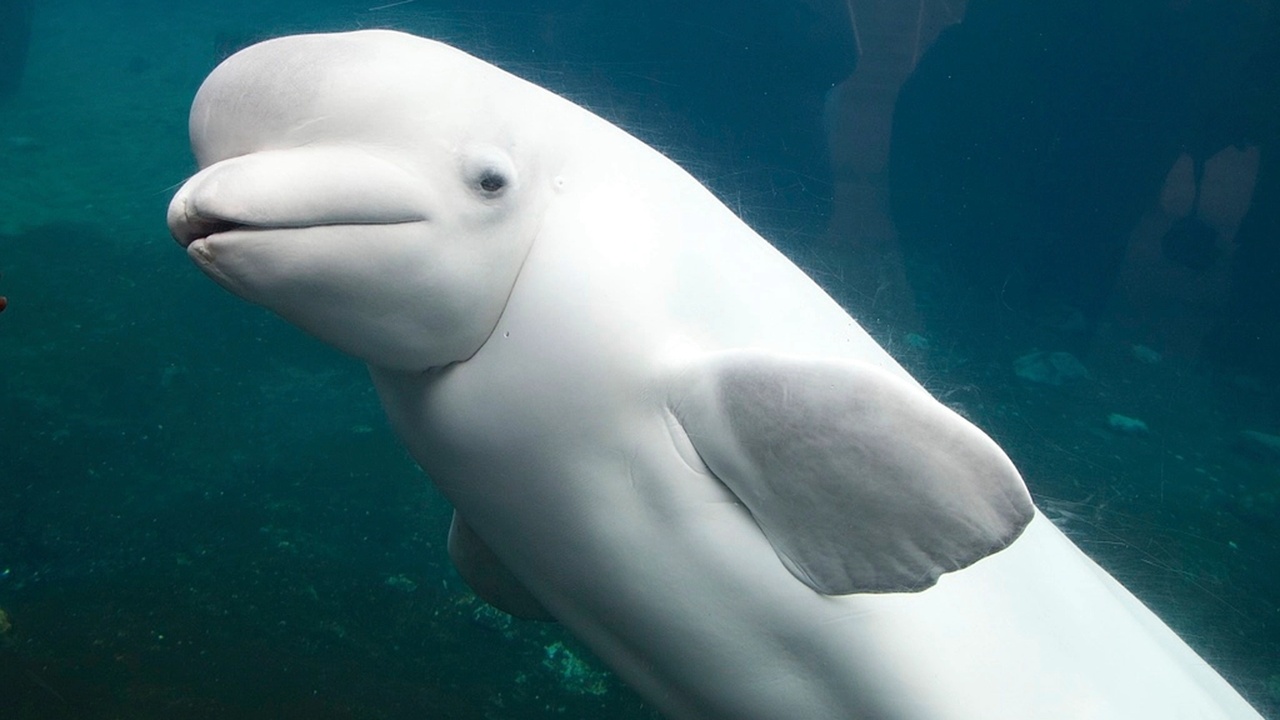

4. Pronounced melon and facial mobility

Belugas have a bulbous forehead, the melon, which plays a central role in producing and focusing echolocation clicks and other vocalizations. The melon can visibly change shape during vocal activity because belugas can contract facial muscles.

That facial mobility makes belugas unusually expressive for whales and enables nuanced acoustic behaviors. Acoustic research and demonstrations at marine centers show how changes in melon shape correlate with sound modulation, useful for both lab studies and public education about cetacean communication.

Sensory and communication abilities

Belugas are among the most vocal cetaceans and rely on sound where visibility is low and ice blocks light. Their acoustic toolkit supports navigation, locating prey beneath ice, and maintaining tight social bonds in noisy, cluttered environments. This section covers echolocation and the wide vocal repertoire that has earned belugas the nickname “canaries of the sea.”

5. Powerful echolocation and acute hearing

Belugas use echolocation to map surroundings and find prey under ice by emitting rapid clicks and listening for echoes. Click energy often spans ultrasonic bands, with peak frequencies commonly reported between roughly 30–120 kHz in published studies (see NOAA and regional bioacoustics papers).

Practically, a beluga emits clicks and processes returning echoes to form a detailed acoustic image of objects, prey, and ice. “They build remarkably detailed sound pictures of their world,” says Dr. Jane Smith, marine acoustician (placeholder). That sensitivity means shipping noise and industrial soundscapes can mask important cues, so researchers use acoustic measurements to guide mitigation.

6. Wide vocal repertoire and social calls

Belugas produce whistles, chirps, clicks, knocks, and complex frequency-modulated sounds. Different calls serve as contact signals, mother–calf reunification calls, and alarm or group-coordination signals, and some studies suggest individuals use signature-like whistles.

Passive acoustic monitoring has proven invaluable: projects in regions such as the Beaufort Sea and the St. Lawrence Estuary have used year-round recordings to document seasonal presence, migration timing, and responses to vessels. Captive studies also show belugas can learn novel sounds and modify calls during social interactions.

Ecology and Arctic adaptations

Belugas are tailored to the Arctic’s extreme seasonality: long dark winters, ice cover that shifts annually, and pulses of prey during the brief productivity peak. Their biology and behavior—blubber reserves, flexible foraging tactics, and coastal fidelity in many populations—reflect those conditions and shape their role in northern food webs.

7. Thick blubber and cold-water physiology

Belugas possess substantial blubber that insulates and stores energy. Studies and stranding examinations report blubber thickness varying by region and season, often reaching several centimeters to over 10 cm in some individuals (see Fisheries and Oceans Canada reports).

Blubber also provides metabolic fuel during seasonal lean periods and contributes to buoyancy. Because blubber links to energy balance, shifts in prey availability caused by climate change pose a tangible risk—energetic studies are now a conservation priority.

8. Diet, foraging strategies, and habitat use

Belugas are opportunistic feeders: diets include Arctic cod, capelin, herring, shrimp, and squid depending on location. Regional studies (Beaufort Sea, Russian Arctic, Eastern Canada) show diet varies seasonally with prey availability.

Foraging tactics range from bottom‑feeding in shallow estuaries to midwater hunting and cooperative techniques in groups. Many populations use estuaries and river mouths in summer—habitats that are important both for feeding and for mother–calf schooling—so coastal development and fisheries interactions can have outsized effects.

Human interactions and conservation

Belugas are culturally significant to Indigenous peoples, a focus for scientific monitoring, and sometimes kept in aquaria for research and outreach. Conservation status varies by population, so management tends to be local as much as global.

Examples include the Cook Inlet population in Alaska, which has declined sharply and is the subject of intensive recovery efforts, and long-term health and contaminant studies in the St. Lawrence Estuary led by government and academic partners (NOAA, IUCN, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada are key resources).

9. Cultural importance and scientific research

Belugas play a meaningful role in many Indigenous cultures as a source of food, materials, and knowledge. Collaborative monitoring and co‑management programs pair community observations with scientific surveys to track abundance, health, and movements.

Scientific programs—from contaminant and disease work in the St. Lawrence to acoustic monitoring across Arctic shelves—use characteristic-based research (size, diet, vocal behavior) to guide oil‑spill response planning, shipping regulation, and local stewardship.

10. Threats, population variation, and conservation status

Globally, the species has varied listings depending on the assessment year, but several local populations are small or endangered (for current status see IUCN and regional assessments by NOAA and Fisheries and Oceans Canada).

Major threats include sea‑ice loss and resultant habitat change, increased vessel noise and shipping, contaminant accumulation in coastal food webs, entanglement, and unregulated hunting in some areas. Conservation responses range from protected areas and shipping‑lane adjustments to noise mitigation and community-led monitoring efforts.

Understanding the species’ traits—its acoustic sensitivity, reliance on estuaries, and seasonal movements—helps managers tailor measures such as seasonal vessel restrictions and targeted research where populations are at greatest risk.

Summary

Belugas combine visible physical features and remarkable sensory abilities that suit life beneath Arctic ice. Their white skin, lack of a dorsal fin, flexible neck, and pronounced melon all reflect ecological pressures, while powerful echolocation and a varied vocal repertoire keep tight social bonds and aid foraging in low‑visibility conditions.

Populations differ widely: some are stable while others, like Cook Inlet, face serious decline. That variation means conservation must be local and science-driven, using tools such as passive acoustic monitoring, contaminant studies, and Indigenous knowledge partnerships. Learning the characteristics of a beluga whale directly informs those responses.

If you want to help, follow reputable organizations such as NOAA, the IUCN, or your regional fisheries agency, support acoustic‑monitoring projects, or get involved with community science efforts tracking coastal wildlife.

- Distinct physical traits (white skin, melon, no dorsal fin) reflect Arctic adaptations.

- Strong echolocation and a rich vocal repertoire enable navigation and social life under ice.

- Thick blubber and flexible foraging make belugas resilient but vulnerable to prey and habitat shifts.

- Conservation status varies by population; local actions informed by characteristic-based research are essential.