Fossil bivalves appear in rocks more than 500 million years old, making clams among the planet’s oldest familiar animals.

But clams are also part of everyday life: they sit on dinner plates, carpet estuaries with beds that clean water, and lock environmental histories into their shells. Understanding the characteristics of a clam reveals why these modest bivalves matter ecologically, economically, and scientifically.

This article organizes ten distinct traits into three groups: Anatomy & Physiology, Behavior & Ecology, and Human Interactions & Conservation. You’ll see how shell form, feeding mechanisms, life history, and human use all connect to bigger coastal questions like water quality and fisheries resilience. Read on to start with the anatomy that makes much of this possible.

Anatomy & Physiology

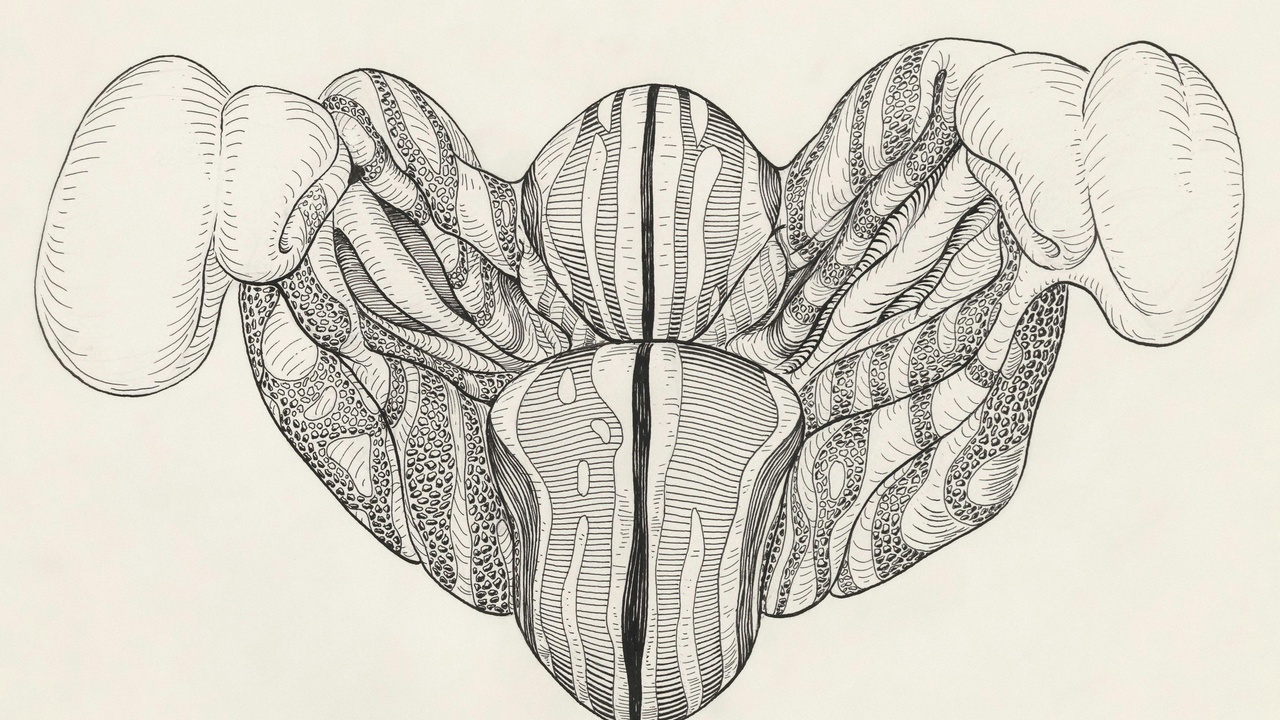

Many defining clam traits are anatomical. Their bivalve anatomy — two hinged shells, a muscular foot, gills, and a mantle — determines how they feed, move, and survive in sediment and on tidal flats.

These structural features have measurable properties. Shells are made mainly of calcium carbonate (aragonite and/or calcite), sizes range from a few millimetres in small littlenecks to tens of centimetres in species like the surf clam, and internal organs scale with lifestyle. Knowing clam structure helps scientists read age and environmental signals from growth rings and shell chemistry.

Below are four anatomical characteristics with evidence, examples, and why they matter for ecology and people.

1. Two-part calcareous shell (bivalve structure)

Clams have two hinged shells composed largely of calcium carbonate, deposited as aragonite or calcite by the mantle. Shells grow by adding material at the margins and leave visible growth rings much like trees.

These shells protect soft tissues, anchor muscles, and provide the durable record used by researchers: shell chemistry and ring patterns track temperature, salinity, and growth history. The fossil record of shell-forming bivalves extends back more than 500 million years.

Examples include the geoduck (Panopea generosa), notable for its large shell and long life, and the Atlantic surf clam (Spisula solidissima), which can reach roughly 20 cm across.

2. Muscular foot for burrowing and anchoring

The muscular foot is a versatile organ used to dig, anchor, and reposition clams in sediment. It expands, contracts, and creates suction to pull the animal downward.

Burrowing speed varies by species; razor clams (Ensis spp.) are fast burrowers able to dig several centimetres per second when escaping a threat. Burrowing reduces predation risk and helps clams stay put in wave-swept environments.

At an ecosystem level, burrowing alters sediment structure, oxygenates substrate, and influences shoreline stability by changing erosion and deposition patterns.

3. Gills adapted for respiration and filter-feeding

Clam gills serve a double duty: they exchange gases and capture food particles from the water. Water is drawn through siphons, across gill surfaces, and out again, while cilia trap and transport plankton and detritus to the mouth.

Filtration rates vary with species and size, but comparable bivalves provide a useful benchmark: an adult oyster can filter about 50 gallons (≈190 liters) of water per day. Beds of clams and oysters together can therefore change local turbidity and nutrient dynamics.

That filtration is ecologically significant: clearer water benefits seagrass, improves juvenile fish habitat, and helps cycle organic matter in estuaries.

4. Mantle and siphons for feeding, excretion, and sensing

The mantle is the soft tissue that secretes shell material and lines the shell interior. Siphons are tubular extensions that control water intake and exit and often carry sensory cells for detecting chemicals and light.

Siphon length often correlates with burrowing depth: species that bury deep, like the geoduck, have long siphons that may extend several centimetres beyond the shell, allowing them to feed and respire while safely buried.

Mantle scars on shells tell researchers about past injuries or repair events, while siphon behavior indicates vulnerability to predators and suitability of sediment habitat.

Behavior & Ecology

Clam behavior and life history shape coastal ecosystems. As filter-feeding bivalves, many clams act as ecosystem engineers: their feeding, movement, and reproduction influence water clarity, nutrient flows, and habitat complexity.

Life-history traits such as lifespan and reproductive output determine how quickly populations respond to disturbance. Some species reproduce in large numbers, while others invest in longevity and slow growth.

Below are three ecological characteristics with numbers, examples, and practical implications for conservation and management.

5. Filter-feeding and ecosystem service (water filtration)

Filter-feeding is a core clam behavior with measurable benefits. Individual filtration rates vary, but using oysters as a benchmark (about 190 liters per adult per day) helps illustrate the scale: dense bivalve beds can process thousands of liters daily per square meter.

That service reduces suspended particles, lowers turbidity, and reclaims nutrients into benthic food webs. Restored bivalve beds in places like Chesapeake Bay and parts of the Pacific Northwest have been linked to improved water clarity and seagrass recovery.

Because rates scale with size and population density, protecting or cultivating dense clam beds is a practical tool for local water-quality improvement.

6. Reproductive strategies and larval dispersal

Many clams are broadcast spawners, releasing eggs and sperm into the water column where fertilization occurs. A single spawning event can release thousands to millions of eggs, depending on species and size.

Larvae typically spend days to weeks as plankton before settling, which allows for wide dispersal but also results in very high early-life mortality. That mix of broad dispersal and low survivorship shapes genetic mixing and local recruitment patterns.

A real-world example is the Manila clam (Ruditapes philippinarum), which spread widely in the 20th century through aquaculture and larval transport, altering local clam communities in some regions.

7. Habitat preferences and geographic range

Clams occupy a range of coastal habitats: intertidal sand and mudflats, subtidal sediments, and estuaries. Substrate type, salinity, and temperature strongly influence where a species thrives.

Some species live intertidally and tolerate exposure at low tide, while others burrow deep in subtidal zones. Depth ranges and temperature tolerances vary by species and determine geographic distribution across temperate and tropical coasts worldwide.

Examples include razor clams on Pacific Northwest beaches and soft-shell clams (Mya arenaria) in New England mudflats. Habitat choice also affects vulnerability to harvest, pollution, and climate-driven changes like sea-level rise.

Human Interactions & Conservation

People have long harvested clams for food, and today they are central to fisheries and aquaculture worldwide. These interactions create economic opportunities but also expose clam populations to overharvest, pollution, and climate stress.

Understanding how these characteristics of a clam affect harvest rates, monitoring, and restoration helps communities balance use and long-term ecosystem health.

The next three points cover fishery importance, monitoring roles, and conservation responses with concrete examples and numbers where available.

8. Role in fisheries and aquaculture

Clams are a major seafood group, with commercially important species including hard clams (Mercenaria), Manila clams, razor clams, and geoduck. Aquaculture supplies much of global demand, especially in parts of Asia and Europe.

Production is large-scale in regions like China and Japan, while the Pacific Northwest supports a lucrative geoduck fishery oriented to export markets. Many regional industries are worth millions of dollars annually and sustain coastal employment.

Aquaculture tools—hatcheries, nursery systems, and grow-out pens—help meet demand and can reduce pressure on wild beds when managed sustainably.

9. Indicators of environmental health and pollutants

Clams bioaccumulate contaminants such as heavy metals and marine toxins, making them useful sentinels for coastal pollution. Tissue and shell analyses provide temporal records of contaminant exposure and environmental change.

Many countries run shellfish monitoring programs that sample tissues at regular intervals—often weekly or monthly during harvest seasons—to detect paralytic shellfish toxins and other hazards and to close fisheries when necessary.

Researchers also use long-term monitoring data to track trends in estuarine contamination, linking pollutant loads to land use, runoff events, and remediation efforts.

10. Conservation challenges and restoration efforts

Major threats to clams include habitat loss, pollution, overharvest, and climate-related stressors like warming and ocean acidification. Some species’ long lifespans mean populations recover slowly after declines—geoducks commonly live more than 100 years, for example.

Restoration approaches include reef or bed re-establishment, hatchery supplementation, and protected zones. Successful projects over the past two decades in places like the Chesapeake and select Pacific estuaries have shown improvements in local water quality and fish habitat within a few years of reef restoration.

Communities can help by supporting restoration groups, choosing sustainably farmed shellfish, and backing monitoring programs that inform safe harvests and habitat protection.

Summary

- Clams trace back more than 500 million years yet remain crucial to modern estuaries through filter-feeding and sediment engineering.

- Shell structure, gills, the muscular foot, and siphons together determine feeding, protection, and habitat use.

- Some species live for decades to more than 100 years, so overharvest and habitat loss can take a long time to reverse.

- Supporting restoration, choosing responsibly farmed clams, and engaging with local monitoring programs are practical steps readers can take.