Coastal communities have long planted and protected mangrove belts for shoreline stability and fish habitat. Early settlements from the Sundarbans to the Caribbean relied on these forests for wood, storm protection, and food, and today mangroves cover roughly 137,000 km² worldwide and include about 80 species (IUCN/FAO estimates).

Mangroves matter because they defend coasts from erosion and storm surge, store large amounts of carbon, and sustain fisheries that support millions of livelihoods (Donato et al., 2011; FAO). Mangrove trees survive and thrive in salty, oxygen-poor coastal environments because of a suite of physical, physiological, and reproductive adaptations — and those adaptations deliver outsized benefits to people and coasts. The sections that follow explain eight key adaptations of mangrove trees and how each helps both the trees and coastal communities.

Structural and Root Adaptations

Mangrove root systems are specialized to anchor trees in soft, shifting sediment, access oxygen in waterlogged soils, and trap sediments that rebuild shorelines. These root architectures reduce erosion, dissipate wave energy, and create complex habitat used as nurseries by fish and crustaceans.

1. Prop and stilt roots (support in soft sediment)

Prop and stilt roots anchor mangroves in unstable mud and break incoming wave energy by creating a lattice of woody supports above the tide line. Species such as Rhizophora produce extensive aboveground prop roots that in dense stands can rise 1–3 m and interlock to form an effective barrier against currents.

Those tangled roots do more than hold trees upright: they trap organic matter and silt, accelerating land building and forming sheltered channels where juvenile snook, snapper, shrimp, and other commercially important species find refuge and forage (NOAA habitat reports document nursery use in Florida mangroves).

2. Pneumatophores and aerial roots (breathing in waterlogged soils)

In oxygen-poor sediments, some mangroves push roots into the air as vertical pneumatophores or develop other aerial structures to access atmospheric oxygen. Avicennia and Sonneratia species commonly produce dense fields of pneumatophores covered in lenticels that facilitate gas exchange down into the submerged root system.

In some forests, pneumatophores occur at tens of thousands per hectare, forming an aerial sponge that lets roots respire where most trees cannot survive. That breathing network is a key reason mangroves colonize anoxic mudflats along coasts from the Gulf Coast to Southeast Asia (examples: Avicennia germinans in Louisiana and Florida).

3. Buttress and anchor root structures (storm resilience)

Buttress and broad anchor roots spread mechanical loads and increase resistance to uprooting during storms, tides, and strong currents. By distributing force across a wide base, these structures make individual trees—and whole belts—less likely to be toppled by high winds or surge.

Post-event assessments from regions such as Bangladesh and studies compiled by UNEP and Conservation International show that intact mangrove belts measurably reduced shoreline erosion and property damage during cyclones, demonstrating how living root defenses contribute to coastal resilience and disaster risk reduction.

Physiological and Biochemical Adaptations

Mangroves employ biochemical tricks to manage salinity and water stress so they can photosynthesize and sequester carbon in saline intertidal zones. These physiological systems—salt exclusion, salt excretion, and osmotic adjustments—also support important services like blue carbon storage (Donato et al., 2011) and water-quality buffering.

4. Salt filtration and exclusion at the root level

Many mangrove species filter salts at the root surface so only limited salt reaches the xylem and leaves. Root membranes and selective ion transport proteins actively exclude Na+ and Cl−, reducing ionic stress in vascular tissues and allowing freshwater physiology in a saline matrix.

Experimental studies report substantial reductions in salt uptake—often on the order of tens of percent in species like Rhizophora—compared with direct seawater concentrations. Root-level exclusion lets these trees take up nutrients and freshwater equivalents even in brackish settings, supporting growth where other woody plants cannot survive.

5. Salt excretion through leaves and salt glands

Other mangroves, notably Avicennia species, actively excrete excess salt through specialized leaf glands. Salt is secreted onto the leaf surface and left as visible crystals after water evaporates, a clear sign of the tree managing its ionic balance to protect photosynthetic tissues.

Measurements of leaf salt excretion rates vary by species and salinity, but the mechanism preserves internal cell function and permits continued growth on high-salinity flats. Field photos from arid tidal zones often show white salt residues on the glossy leaves of Avicennia marina.

6. Water-use efficiency, waxy leaves, and osmotic adjustments

Leaves of many mangroves have thick cuticles, sunken stomata, and reduced stomatal density, all of which lower transpiration and conserve water during tidal inundation and salt stress. Biochemical osmolytes such as proline and soluble sugars accumulate to maintain cellular turgor.

These traits—combined with leaf anatomy seen in Sonneratia alba and the waxy, leathery leaves of Rhizophora—allow sustained photosynthesis under saline conditions and help mangroves persist where freshwater is limited and evaporative stress is high.

Reproduction, Dispersal, and Ecological Strategies

Mangrove reproductive strategies—vivipary, buoyant propagules, and close partnerships with soil microbes—enable rapid colonization of new sediment, genetic mixing across coastlines, and nutrient cycling that supports recovery after disturbance. These ecological strategies are central to how mangroves expand and persist on dynamic shores.

7. Vivipary: live-bearing propagules that germinate before release

Vivipary means seeds germinate while still attached to the parent tree, producing elongated, live propagules ready to root on landing. This head start boosts establishment success compared with dormant seeds that must first germinate in situ.

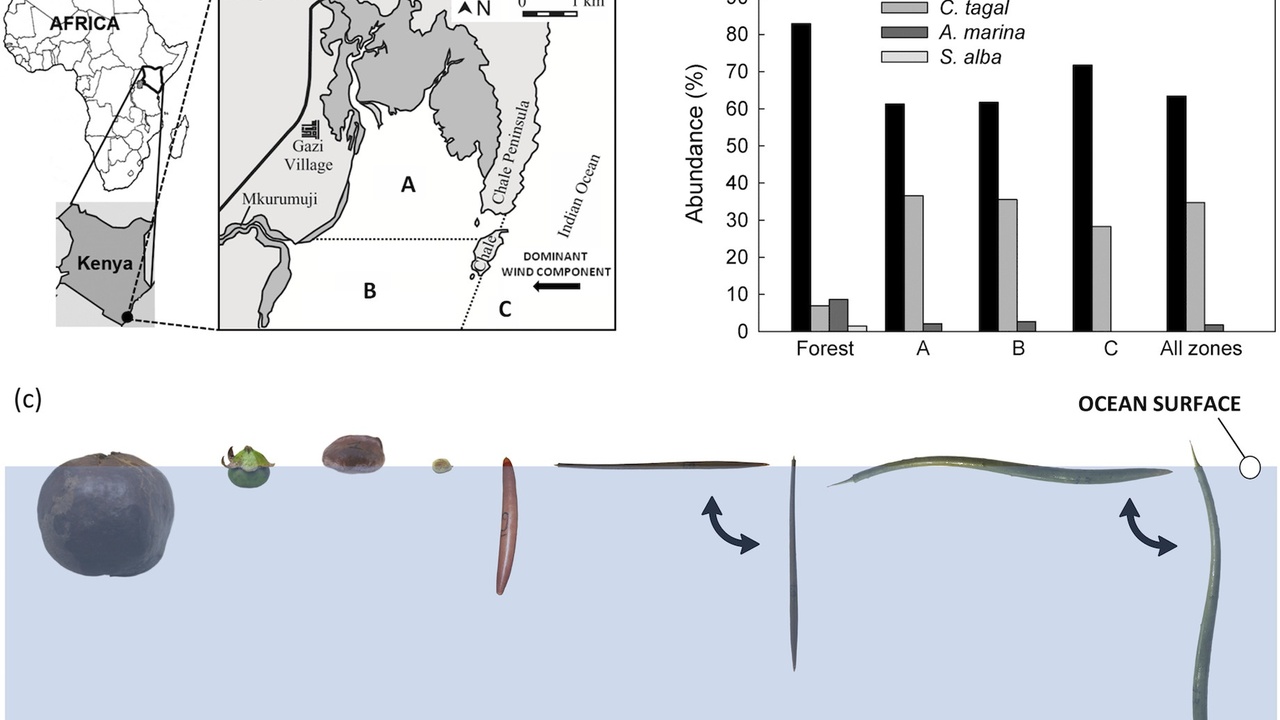

Many Rhizophora and Bruguiera propagules remain buoyant and viable for weeks to months, with field drift studies reporting typical dispersal durations of roughly 2–8 weeks depending on currents and species. Practitioners use viviparous propagules in restoration because they establish quickly on newly deposited mud and sand.

8. Propagule dispersal, colonization timing, and microbial partnerships

Buoyant propagules combined with tidal timing maximize colonization: propagules that settle during neap tides and low-energy periods have higher survival. Long-distance dispersal increases genetic mixing and lets mangroves recolonize islands, estuaries, and coastlines after storms (field studies document dispersal across tens to hundreds of kilometers in some cases).

Belowground, mangrove rhizospheres host microbes that recycle nutrients, fix nitrogen in some contexts, and detoxify sulfides—processes essential for seedling nutrition and soil health. Restoration projects often align propagule planting with favorable tides and substrate conditioning to harness these biological partnerships for better survival.

Summary

- Specialized root architectures—prop roots, pneumatophores, and buttresses—stabilize sediment, trap silt, and act as living coastal defenses.

- Physiological systems—root-level salt exclusion, leaf salt glands, and osmotic adjustments—allow mangroves to maintain water balance and photosynthesis in saline, anoxic soils (see Donato et al., 2011; IUCN/FAO reports).

- Reproductive strategies like vivipary and long-lived, buoyant propagules enable rapid colonization and effective restoration practice when timed with tides and local hydrodynamics.

- These adaptations deliver practical benefits—shoreline protection, nursery habitat for fisheries, and significant blue carbon storage—so restoring and protecting mangroves is a high-value nature-based solution.

- Take action: support local mangrove restoration efforts, consult IUCN/FAO guidance, or advocate for nature-based coastal defenses in planning and policy.