Sea ice in the Arctic has declined by roughly 40% in late summer since 1979, and with those changing conditions many familiar species are shifting ranges and behavior. That loss of frozen habitat doesn’t just reshape polar landscapes; it alters food webs, undermines subsistence practices, and gives scientists early-warning signs about global climate trends.

This article profiles ten iconic Arctic animals to explain how each one is uniquely adapted to extreme cold, why they matter ecologically and culturally, and what current threats mean for their future. Read on for clear examples of adaptations, conservation status, and human connections — from community hunting practices to ecotourism case studies.

H2: Iconic Arctic Mammals

Large mammals like bears, foxes, hares and muskoxen are keystone and culturally important species across tundra and pack-ice zones. They structure food webs by moving energy between plants, small mammals and top predators, and many communities rely on them for subsistence, stories, and livelihoods. Their fates are closely tied to sea ice and temperature trends (see IUCN, NOAA).

1. Polar bear (Ursus maritimus)

The polar bear is the Arctic’s apex predator and the best-known icon of sea-ice ecosystems. The IUCN’s 2018 assessment estimates roughly 22,000–31,000 polar bears globally and lists the species as Vulnerable (IUCN 2018).

Adaptations include a thick blubber layer for insulation, black skin beneath dense fur to absorb heat, and very large, slightly webbed paws that spread weight on ice and aid swimming. Declining summer sea ice shortens access to seal hunting grounds, reducing condition and cub survival. For humans, polar bears are central to Indigenous knowledge and also to tourism: guided polar-bear viewing in Svalbard attracts roughly tens of thousands of visitors annually, bringing revenue but also management challenges. Communities in Nunavut use bear patrols, fortified food storage, and local alert systems to reduce dangerous encounters, integrating traditional knowledge with modern safety measures (WWF, NOAA).

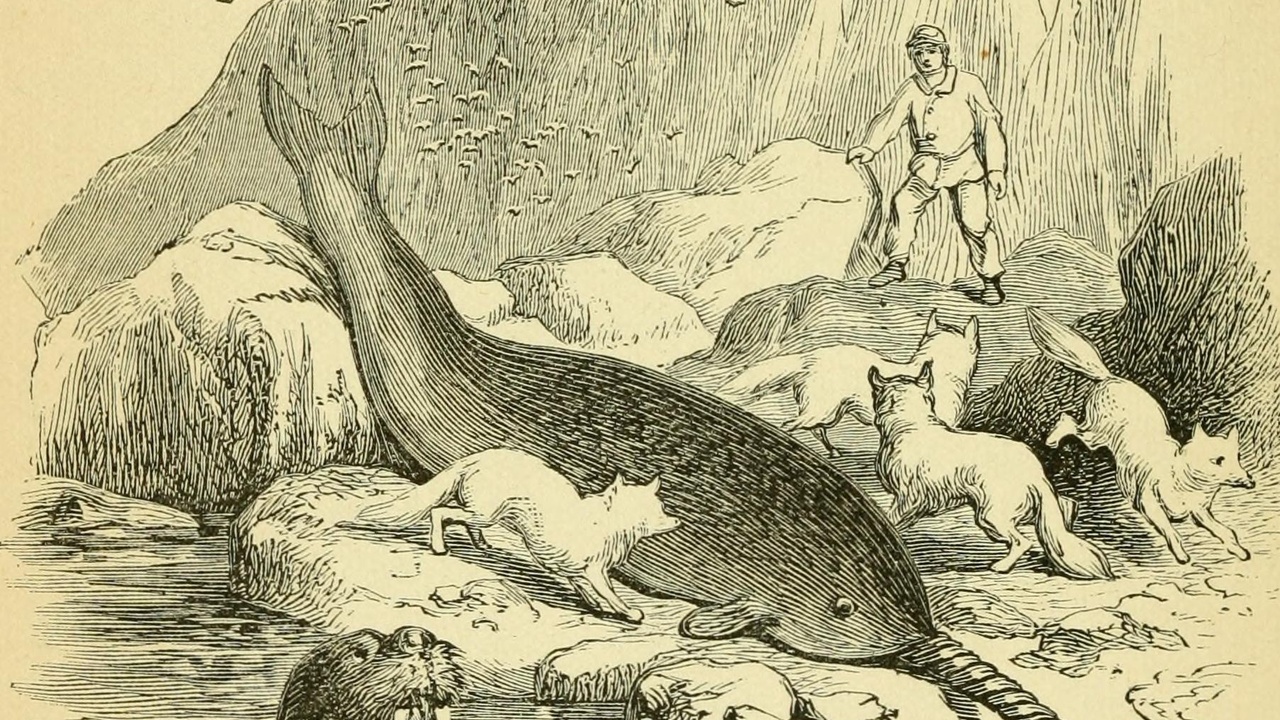

2. Arctic fox (Vulpes lagopus)

The Arctic fox is a nimble tundra predator and scavenger with one of the most striking seasonal coat changes in mammals. Individuals typically weigh about 3–8 kg and have a circumpolar distribution, ranging from Scandinavia to Alaska.

Foxes track multi-year lemming cycles: in peak lemming years fox reproduction and juvenile survival rise, while in low phases fox numbers fall. They also scavenge leftovers from polar-bear kills, linking terrestrial and marine food chains. Researchers in Scandinavia and Alaska have long-term data showing how fox demographics mirror small-rodent pulses, and their seasonal camouflage has inspired materials science work on color-changing surfaces. Small settlement conflicts occasionally arise where foxes scavenge poultry or garbage, prompting community-level controls and coexistence planning (NINA research examples).

3. Arctic hare (Lepus arcticus)

The Arctic hare is widespread across tundra habitats and switches coats with the seasons for camouflage. Typical body length ranges from about 40–70 cm, with weights commonly between 2.5 and 5.5 kg.

Hares are a key prey species for foxes, snowy owls and humans historically; in good years they can raise multiple litters, bolstering predator populations. After mild winters or abundant forage, hare numbers can spike locally, which in turn supports more breeding by predators. Subsistence hunters in Greenland and northern Canada have long relied on hares for meat and fur, demonstrating the species’ cultural as well as ecological value.

4. Muskox (Ovibos moschatus)

The muskox is a shaggy, herd-forming Arctic grazer with roots in the Pleistocene; males can reach weights up to around 400 kg. Muskoxen form tight defensive circles against wolves, a behavior that reduces predation risk for calves.

As heavy grazers, muskoxen influence tundra plant communities and local carbon dynamics by consuming woody shrubs and redistributing nutrients through trampling and feces. Their Pleistocene lineage attracts genetic interest, and reintroduction programs—such as translocations to parts of Norway and historic rewilding efforts—illustrate how management can restore lost functionalities. Muskox-related ecotourism and sustainable harvests provide livelihoods in some regions, but managers monitor populations carefully to avoid overexploitation.

H2: Arctic Marine Mammals

Marine mammals—from walrus to whales—dominate coastal and pack-ice systems, moving nutrients between deep benthic zones and surface waters. These Arctic animals support Indigenous subsistence, act as sentinels of ocean health, and play outsized roles in nutrient cycling; population shifts often reflect warming seas and changing ice patterns (NOAA, IUCN).

5. Walrus (Odobenus rosmarus)

The walrus is a large pinniped adapted to hauling out on ice and shorelines. Adult males commonly range from about 800 to 1,700 kg, and long tusks serve for hauling onto ice, dominance displays, and social signaling.

Walruses feed primarily on benthic invertebrates such as clams, sucking prey from the seafloor and in the process redistributing sediments and nutrients. Reduced sea ice in some regions has forced animals onto beaches in massive haul-outs; Alaska researchers have documented gatherings of thousands onshore, which raises calf mortality from trampling and increases exposure to disturbance. Indigenous communities continue subsistence harvests under local management rules, balancing cultural needs and population sustainability. Conservation and monitoring efforts by NOAA and local partners track haul-out trends and population status (NOAA walrus information).

6. Narwhal (Monodon monoceros)

Narwhals are best known for the males’ long, spiraled tusk — a modified canine that can reach about 2–3 meters in length. They have a circumpolar distribution and show strong fidelity to summering fjords such as Scoresby Sound in East Greenland.

Narwhals form dense summer aggregations in specific inlets, making those fjords culturally and economically important for Inuit communities that hunt them sustainably. Scientists are still testing tusk functions — sensory roles, sexual selection, or social signaling have been proposed — and narwhals are highly sensitive to noise and ship traffic because they rely on quiet, ice-covered waters for diving and feeding. Survey teams and local knowledge together document migration routes and aggregation sizes to guide protective measures (IUCN, local scientific surveys).

7. Beluga whale (Delphinapterus leucas)

Nicknamed the “canary of the sea,” the beluga is highly vocal and often uses shallow coastal estuaries for calving and feeding. Adults typically measure about 3–5 meters in length, and many populations are tightly linked to specific bays and rivers.

Belugas are prey for orcas in some regions and are a key subsistence species for coastal communities. Long-term monitoring programs—such as studies in Cook Inlet, Alaska—have highlighted how noise pollution, contaminants and habitat loss can depress local populations; some stocks number only a few hundred animals and are considered of conservation concern by NOAA. Continued monitoring and noise mitigation near estuaries are central management priorities (NOAA beluga resources).

8. Bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus)

The bowhead is a true Arctic specialist and among the longest-lived mammals; individuals with ages exceeding 200 years have been documented using harpoon fragments and eye tissue analysis. Certain stocks are now estimated in the low tens of thousands following partial recovery from commercial whaling (NOAA stocks).

Bowheads play roles in nutrient cycling by transporting carbon-rich biomass through migration and are central to many Indigenous cultures for meat, oil and materials. Conservation successes include careful co-management and protected migration corridors, but threats remain from increased shipping, noise, and changing ice that can alter feeding grounds. Long-lived species like bowheads also teach us about multi-decadal environmental change because individual whales integrate conditions over centuries.

H2: Notable Arctic Birds

Birds link marine and terrestrial systems in the Arctic and include extreme migrants that connect hemispheres. Seabirds and shorebirds act as predators, nutrient vectors from ocean to land, and timely indicators of changing phenology and food availability. Monitoring their breeding colonies reveals broader ecosystem shifts.

9. Snowy owl (Bubo scandiacus)

The snowy owl is a conspicuous tundra predator and an irruptive winter visitor to lower latitudes when rodent abundance is low. Wingspan ranges roughly from 1.2 to 1.5 meters, and their primary prey on the breeding grounds is the lemming.

Snowy owl breeding success tracks multi-year lemming cycles: in high-rodent years owls produce larger clutches and more fledglings. These boom years create irruptions that excite birders and support ecotourism in places like Canada’s Arctic islands. Long-term monitoring projects in Canada and Greenland document these boom-bust dynamics and help managers anticipate conservation needs for both predator and prey.

10. Atlantic puffin (Fratercula arctica)

Puffins nest on Arctic and sub-Arctic cliffs in large colonies and are among the most charismatic seabirds. They dive for small fish, reaching depths up to about 60 meters to catch forage species for chicks.

By transferring marine nutrients to nesting areas, puffin colonies fertilize coastal soils and support plant communities. Threats include declines in key forage fish and warming seas shifting prey distribution. Large colonies in Iceland, the Faroe Islands and Newfoundland are important for coastal ecotourism; seabird monitoring programs track colony sizes and diet composition to guide conservation action.

Summary

- Arctic species are highly specialized for cold environments but vulnerable to rapid change; shrinking sea ice and warming seas are altering ranges, behavior and survival.

- These animals are both ecological linchpins and cultural touchstones — from bowheads and narwhals in Indigenous diets and stories to polar bears and puffins that support local tourism economies.

- Numbers and facts matter: sea ice has fallen ~40% in late summer since 1979; polar bears number about 22,000–31,000 (IUCN 2018); narwhal tusks reach ~2–3 m; walrus bulls weigh 800–1,700 kg; bowheads can exceed 200 years of age. Use authoritative sources like IUCN, NOAA, and WWF for details.

- Practical actions include supporting Indigenous-led conservation, funding reputable research and monitoring, and reducing greenhouse-gas emissions to slow habitat loss; learning more about Arctic animals and donating time or money to trusted groups is a tangible start.