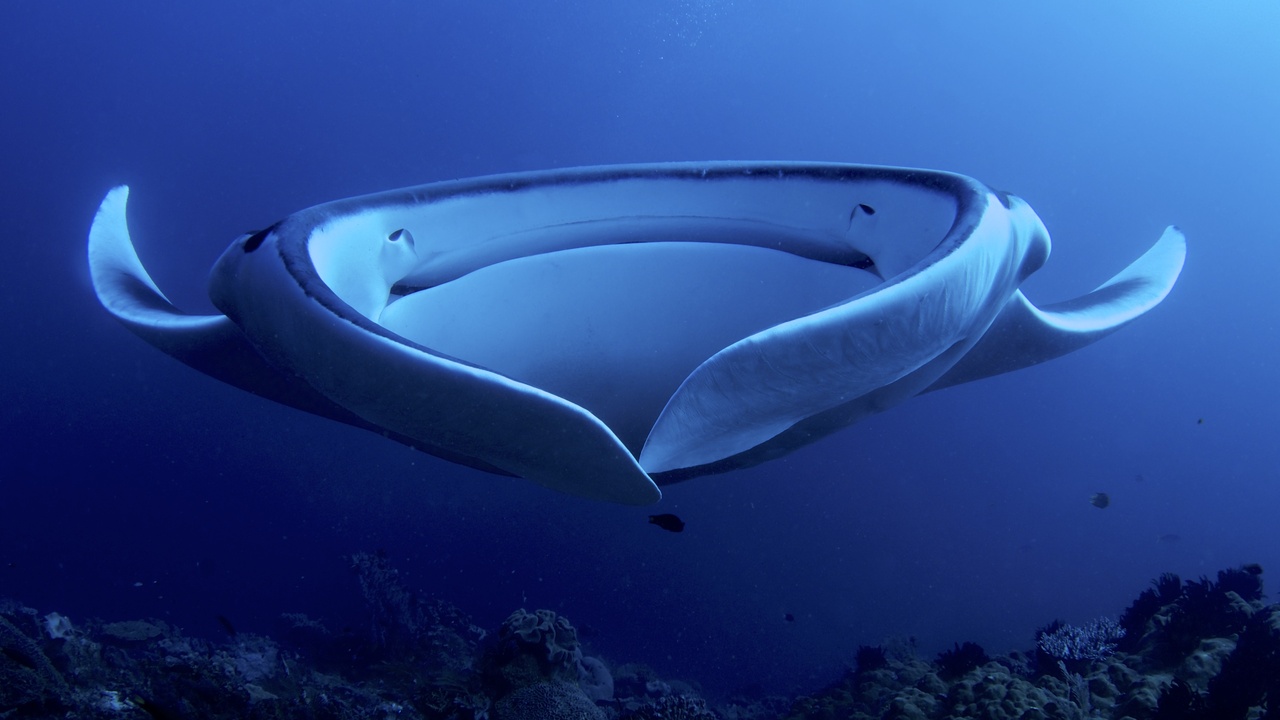

Some giant manta rays can span up to 7 meters (about 23 feet) from wingtip to wingtip—larger than many small cars. That size alone draws divers, scientists, and coastal communities to encounter these animals, but mantas are fascinating for many other reasons. There are two widely recognized manta species: the giant manta (Manta birostris) and the reef manta (Manta alfredi), and their combination of anatomy, feeding systems, and social behaviors makes them unusually visible and valued in ocean ecosystems.

Understanding the characteristics of a manta ray helps managers design protected areas, tour operators run safe encounters, and researchers target the right questions for conservation. This piece outlines ten defining traits—grouped by anatomy, sensory and feeding adaptations, life history, and human interactions—that explain why mantas matter ecologically and economically.

The tone here is conversational but evidence-based. Expect concrete numbers (wingspans, gestation lengths, migration distances), named studies or programs (photo‑ID catalogs, satellite tagging), and practical implications for tourism and policy.

Physical and anatomical traits

These are the visible, anatomical features that make manta rays recognizable. Anatomy links directly to function: broad, wing-like pectoral fins produce lift and allow a manta to “fly” through water, while the head and mouth structures are specialized for filtering tiny prey. The giant manta and the reef manta differ mainly in size and habitat use, but both show how external form supports ecology and human interactions.

1. Large wingspan and streamlined body

Mantas have extremely large, wing-like pectoral fins and a diamond-shaped, streamlined body. Giant mantas can reach wingspans up to 7 m (23 ft), while adult reef mantas are smaller on average—commonly 3–5 m across.

That size affects buoyancy, cruising speed, and how quickly they gain or lose heat in varying waters. Larger individuals travel farther and can cross thermal gradients, which matters for where they feed and breed.

For people, size influences visibility for dive tourism, the risk of boat strikes near surface feeding, and how managers design protected areas and boat‑traffic rules. For example, a 2015 Pacific tagging study tracked giant mantas moving between islands, showing adults can traverse hundreds of kilometers.

2. Cephalic fins and wide, forward-facing mouth

On either side of the head mantas have cephalic fins—curled lobes that unfurl like scoops to channel plankton into a large, terminal mouth at the front of the head. Unlike bottom-feeding rays, mantas feed in the water column with an open, forward mouth.

Inside the mouth, densely packed gill rakers act as filters. Observational studies estimate a single feeding pass can process hundreds of liters of water per minute, depending on prey density and swim speed. Gill-raker density varies with size and species.

This apparatus makes mantas efficient filter feeders but also vulnerable to gill-net bycatch. Cleaning stations and surface upwellings concentrate plankton, explaining why mantas repeatedly visit the same reefs where food is predictable.

3. Flexible pectoral fins that enable efficient ‘flying’ locomotion

Manta pectoral fins are highly flexible and produce an undulating, wing-like stroke rather than the steady tail-driven motion seen in many fishes. Hydrodynamic studies compare this motion to wing lift in air, showing efficient thrust and low energy cost at cruising speeds.

That efficiency supports long-distance travel and gliding between feeding pockets. Engineers have used manta fin kinematics as inspiration for bio‑inspired underwater vehicles and soft-propulsion designs.

Feeding, sensory, and physiological adaptations

This category covers how mantas find, capture, and process food, plus the sensory and physiological traits that support those behaviors. Mantas are specialized filter feeders with keen sensory systems and relatively large brains for fishes.

4. Filter-feeding diet focused on plankton and small schooling fish

Mantas are obligate filter feeders that consume zooplankton, copepods, and sometimes small schooling fish. In dense prey patches they perform barrel-rolls or surface lunges to maximize intake.

Observers have recorded chain-feeding events where multiple mantas take turns passing through a rich plankton patch. Typical feeding events last seconds to minutes, with several passes when prey density is high. Changes in plankton abundance from warming or nutrient shifts could reduce feeding opportunities and affect local manta numbers.

5. Advanced sensory systems: vision, electroreception, and lateral-line sensing

Mantas combine good eyesight with electroreception (ampullae of Lorenzini) and a sensitive lateral line. These complementary systems let them detect prey patches, navigate around reefs, and approach cleaning stations with precision even in low light or murky water.

Anatomical studies show ampullary canals similar to those of sharks, while behavioral observations document careful inspection of hosts at cleaning stations and deliberate approaches to divers and cameras, indicating fine spatial awareness.

6. Large brain-to-body ratio and signs of social intelligence

Researchers report that mantas have a relatively large brain for fishes, with an expanded telencephalon that is associated with learning and complex behavior. This neuroanatomy aligns with field observations of social interactions.

Examples of social complexity include orderly queues at cleaning stations, coordinated group feeding, and repeated individual appearances at the same dive sites (photo‑ID catalogs document repeat visitors). Those patterns suggest learning, memory, and perhaps simple social traditions.

Behavior, life history, and movement

Manta life history combines longevity with slow reproduction and strong movement patterns: long lives, delayed maturity, low fecundity, and a mix of long-distance migration and tight site fidelity to key reef features.

7. Long lifespan and slow reproductive rate

Mantas mature slowly and reproduce infrequently. Gestation lasts approximately 12–13 months, and females typically give birth to a single pup. Sexual maturity is reached several years after birth, depending on species and growth rates.

Typical lifespan estimates range widely—commonly 20–50 years—so population recovery after declines can take decades. That low fecundity makes mantas especially vulnerable to fishing pressure and bycatch, a point emphasized by conservation assessments.

8. Migration tendencies and site fidelity to cleaning stations

Mantas display both long-distance movement and strong fidelity to particular reef sites. Photo‑ID catalogs from the Maldives and Revillagigedo, plus satellite tags from Kona and other sites, show annual returns to cleaning stations and migrations that can span hundreds to more than 1,000 km.

Cleaning stations act as ecological hubs where social interactions, parasite removal, and mate inspection occur. Protecting both these predictable sites and the corridors mantas use is important for effective conservation.

Conservation status and human interactions

Human activities intersect with manta biology through fisheries bycatch, targeted take for gill rakers, and growing manta-watching tourism. International and national policies respond to these threats while also recognizing economic benefits from live animals.

9. Vulnerability to fisheries, bycatch, and international trade

Mantas were added to CITES Appendix II in 2013, a step that regulates international trade in their parts and products (CITES). IUCN assessments list species-level risk categories and provide population trend details; consult IUCN for current listings.

Targeted fisheries for gill rakers and incidental capture in gill nets and longlines have driven local declines. Because mantas reproduce slowly, even modest levels of adult removals can cause rapid drops and slow recovery.

10. High ecotourism value and research importance

Manta-watching supports local economies in the Maldives, Hawaii (Kona), parts of Indonesia, and Australia. Dive operators often report substantial income tied to manta tourism and invest in photo‑ID and citizen‑science programs that help track individuals over years.

Photo‑ID catalogs and volunteer submissions provide long-term data used in population monitoring and management. Best-practice tourism guidelines—no‑touch rules, minimum approach distances, and limited swim times—help reduce disturbance while maintaining economic benefits.

Summary

Here are the main takeaways about the characteristics of a manta ray and why they matter for conservation and tourism.

- Huge wingspans (up to 7 m) and streamlined bodies make mantas efficient open-water feeders and highly visible to divers.

- Specialized cephalic fins, gill rakers, and advanced senses support obligate filter feeding on plankton and coordinated feeding behaviors.

- Slow life history—~12–13 month gestation, usually one pup, and late maturity—means populations recover slowly after declines; CITES Appendix II (2013) and IUCN assessments reflect that vulnerability.

- High ecotourism value, strong site fidelity to cleaning stations, and effective photo‑ID programs give managers tools to protect mantas while supporting local livelihoods.