CDC estimates roughly 476,000 Americans are treated for Lyme disease each year (2010–2018), a figure that highlights how common tick-borne infections have become in many parts of the United States.

Ticks matter because they affect human and animal health, influence wildlife ecology, and shape how we use yards, parks, and trails. These tiny arachnids can change the seasonality of outdoor activities and create real veterinary and public-health concerns.

Ticks are blood-feeding arachnids, not insects, with body plans and behaviors that make them effective parasites and disease vectors. This article explains 10 essential characteristics of a tick that you can observe, understand, and act on.

The content is organized into three major sections — anatomy, life cycle & behavior, and feeding & interactions — and lists ten discrete characteristics with species examples and practical tips for prevention.

Anatomy and Physical Features

1. Arachnid body plan: capitulum and idiosoma; leg counts

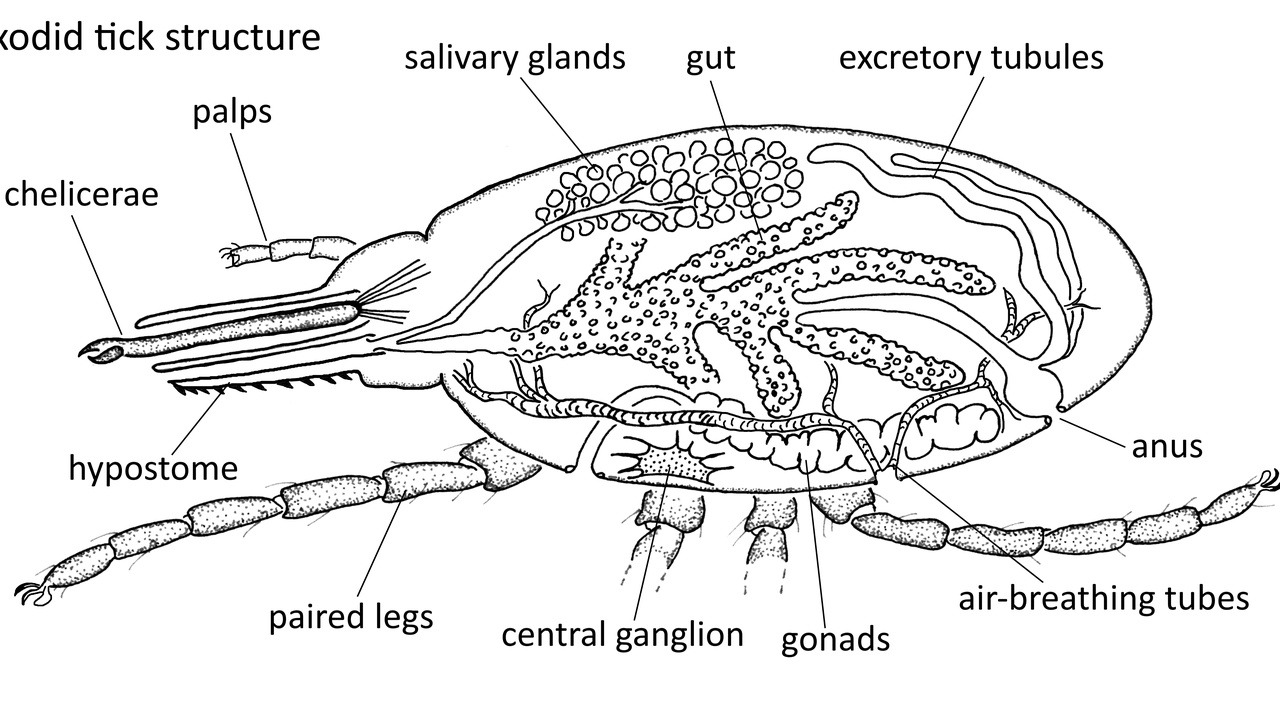

Ticks are arachnids (relatives of spiders and mites) with two principal body regions: the capitulum, which bears the mouthparts, and the idiosoma, which contains the legs and internal organs. Larval ticks hatch with six legs, while nymphs and adults have eight.

That change in leg count helps entomologists and backyard naturalists distinguish life stages: tiny “seed ticks” (larvae) are often overlooked, while eight-legged nymphs are the life stage most implicated in human Lyme infections because they’re small and hard to spot.

Globally, researchers describe roughly 900 tick species, and species like Ixodes scapularis (blacklegged tick) and Dermacentor variabilis (American dog tick) exemplify these body-plan traits.

2. Specialized mouthparts for blood feeding (hypostome and chelicerae)

Ticks use chelicerae to cut the skin and a barbed hypostome that anchors them while they suck blood. The hypostome’s backward-facing barbs and secreted, cement-like substances help the tick remain attached for days, increasing feeding efficiency.

Many unfed ticks measure only 1–3 mm long but can swell to 10 mm or more when engorged, demonstrating how these mouthparts support large-volume feeding. Improper removal can leave mouthparts embedded and raise the risk of local inflammation or infection.

Close-up images of Ixodes species show the hypostome’s barbs clearly; in practice, those structures explain why an attached female can feed uninterrupted for long periods.

3. Scutum and sexual dimorphism: how males and females differ

A dorsal scutum — a hardened plate — varies between male and female ticks. Males typically have a scutum that covers most of the back, which limits how much they can engorge, while females have a smaller scutum so their abdomen can expand dramatically during feeding.

Female ticks can increase their body mass by roughly 10–100 times during a single blood meal, and a single engorged female may lay many hundreds to a few thousand eggs (typical clutch sizes range from about 1,000–3,000 eggs depending on species).

That sexual dimorphism matters ecologically and for identification: engorged females (for example, Dermacentor or Ixodes species) are the life stage responsible for producing the next generation after feeding.

4. Haller’s organ and host-sensing abilities

On the first pair of legs most ticks carry Haller’s organ, a sensory pit that detects carbon dioxide, skin odors, humidity, and temperature gradients. This organ allows ticks to detect hosts at very low concentrations of volatile cues and to time their host-seeking activity.

Haller’s organ explains common behaviors such as climbing vegetation and adopting a questing posture with legs extended to latch onto passing hosts. Behavioral studies show strong attraction to CO2 plumes and heat, which helps explain why trails and lawn edges concentrate tick encounters.

Life Cycle, Behavior, and Ecology

5. Four-stage lifecycle: egg, larva, nymph, adult (often 2–3 years)

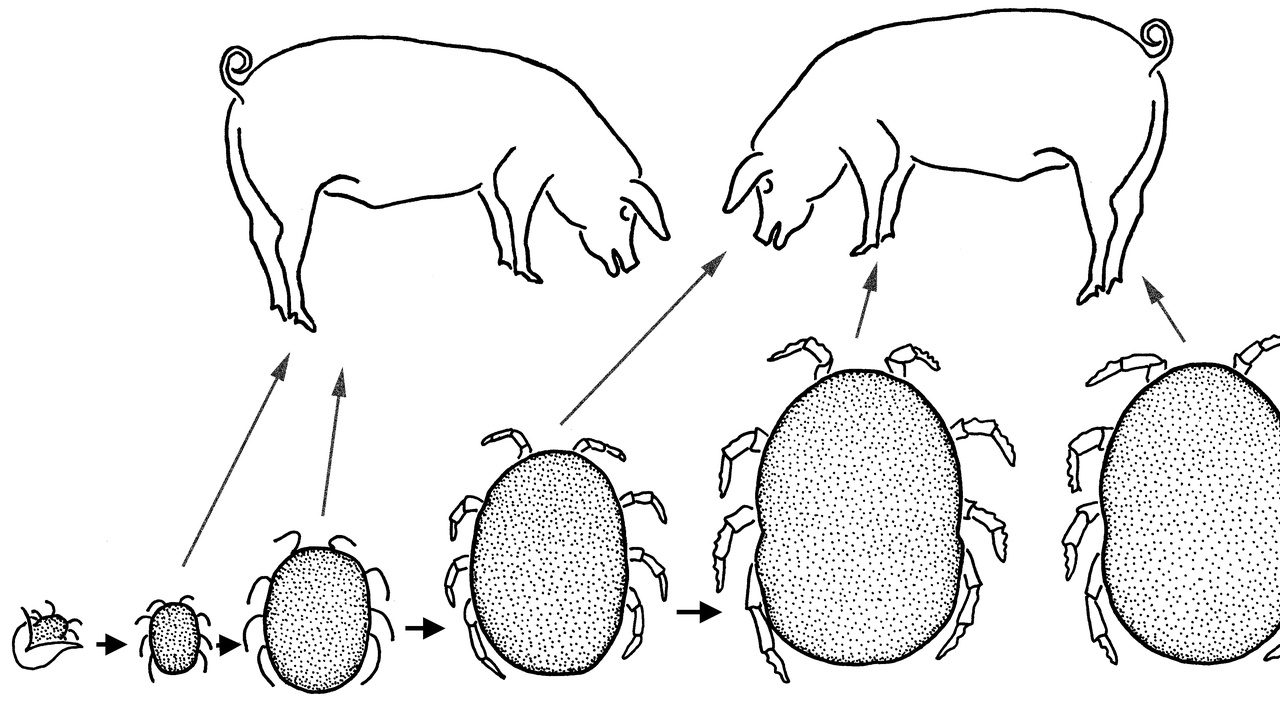

Most hard ticks follow four stages: egg → larva → nymph → adult. Many medically important species, such as Ixodes scapularis, follow a three-host cycle in which each active stage feeds on a different host before dropping off to molt.

In temperate regions, completing the cycle commonly takes 2–3 years, though climate and host availability can speed or slow this timing. Larvae hatch in large numbers — clutches often exceed 1,000 eggs — feed on small hosts like rodents, then molt into nymphs.

Ecologists tracing the deer–tick–Lyme connection documented key links in the 1970s, and those life-stage dynamics help explain why nymphs — small and easy to miss — disproportionately drive human Lyme disease cases.

6. Questing and host-seeking strategies

Questing is the posture ticks adopt on low vegetation to latch onto passing hosts: they climb stalks or leaf litter and hold up their front legs to sample air and touch potential hosts. CO2, body heat, skin odor, and vibration trigger this behavior.

Seasonal patterns depend on life stage and region; for example, nymphs in the northeastern U.S. usually peak in late spring to early summer, while some adult activity rises again in autumn. Ticks also seek sheltered microhabitats to avoid desiccation, which concentrates them in leaf litter and along trail edges.

A practical tip: checking lower legs, behind knees, and the groin after outdoor activity reduces the chance that a questing nymph goes unnoticed.

7. Environmental resilience and geographic distribution

Ticks occur worldwide — on every continent except Antarctica — with about 900 described species adapted to a wide range of climates. Many can survive months to over a year between blood meals by entering low-metabolic states in protected microhabitats.

Range shifts over recent decades — driven by climate change, reforestation, and changes in host populations — have expanded species like Ixodes scapularis into new areas. Suburban yards, fragmented forests, and edge habitats can support high tick densities close to people.

Resilience to environmental extremes often depends on behavioral sheltering (burrowing into leaf litter or seeking shaded vegetation) rather than physiological tolerance alone.

Feeding, Reproduction, and Human–Animal Interaction

8. Blood-feeding and pathogen transmission (vectors of bacteria, viruses, protozoa)

Ticks are efficient vectors because prolonged attachment gives pathogens time to migrate from tick saliva or gut into the host. Lyme disease is the most commonly reported vector-borne illness in the U.S.; CDC estimates roughly 476,000 Americans are treated for Lyme disease annually (2010–2018).

Ticks transmit bacteria (Borrelia burgdorferi, Rickettsia rickettsii), protozoa (Babesia microti), and viruses (Powassan virus), among others. Transmission risk often increases with attachment duration for many pathogens, so early detection and correct removal matter.

Practical removal guidance from public-health authorities emphasizes using fine-tipped tweezers to pull straight out and then cleaning the bite site; leaving embedded mouthparts can prolong local inflammation and complicate diagnosis.

9. Host specificity and preferred hosts (from rodents to large mammals)

Some ticks are generalists while others show strong host preferences. Ixodes scapularis feeds on small mammals (notably white-footed mice), deer, and humans, whereas Rhipicephalus sanguineus, the brown dog tick, specializes on canids and can infest kennels and homes.

Ecological roles vary: rodents often amplify pathogens as reservoir hosts, whereas deer sustain adult tick populations by supporting reproduction. That division of roles explains why managing small-mammal reservoirs and deer densities influences local disease risk.

Pet owners should use veterinarian-recommended preventatives because pupating brown dog ticks and other dog-focused species can be brought indoors and establish infestations.

10. Control, prevention, and public-health importance

Many tick-borne infections are preventable with basic measures. Personal protection — permethrin-treated clothing, EPA-registered repellents such as DEET or picaridin, and routine tick checks — reduces bite risk significantly when used correctly.

Landscape steps (removing leaf litter, creating gravel borders between lawns and woods), pet treatments (spot-on products, tick collars), and community awareness campaigns also lower exposure. Permethrin-treated fabrics remain effective through several launderings if used per label instructions.

Historically, a human Lyme vaccine (LYMErix) was available from 1998–2002; vaccine research continues but there is not a widely used human Lyme vaccine in broad circulation today. Community-level interventions and veterinary partnerships remain vital for reducing cases.

Summary

- Ticks are arachnids with specialized anatomy (mouthparts, scutum, Haller’s organ) that enable prolonged blood feeding and effective host detection.

- Their multi-stage lifecycle (egg → larva → nymph → adult), often taking 2–3 years, and questing behavior concentrate human risk in predictable seasons and habitats.

- Ticks transmit bacteria, viruses, and protozoa; prevention focuses on repellents, permethrin-treated clothing, landscape management, and prompt tick checks and removal.

- Understand the characteristics of a tick to protect yourself and your pets: use vet-recommended preventatives, inspect after outdoor activity, and consult local public-health guidance about area-specific risks.