Around 370 million years ago, four-legged vertebrates emerged from water onto land — the distant ancestors of modern amphibians.

That deep origin helps explain why these animals bridge two worlds. Amphibians play outsized roles in pest control, nutrient cycling and food webs, and they also serve as early-warning signs for environmental trouble. Scientists study them for insights into development, regeneration and emerging diseases. There are around 8,000 known species, and about 40% face some level of threat, so what happens to amphibians matters to ecosystems and people alike.

Below I group ten defining traits into three clear categories — anatomical and physiological features, life-history and reproductive strategies, and behavioral and ecological roles — so you can see what makes these animals distinct and why they need attention. This piece lays out those ten traits, with real examples and practical conservation links.

Anatomical & Physiological Traits

Amphibian bodies show a suite of features adapted to both water and land, though frogs, salamanders and caecilians each emphasize different solutions.

Below are four core anatomical and physiological traits that reflect their early tetrapod heritage and their modern ecological niches.

1. Permeable Skin and Cutaneous Respiration

Many amphibians breathe through their skin as well as with lungs. Thin, well-vascularized epidermis allows gases and water to cross the body surface, and in some species cutaneous exchange provides a significant share of oxygen uptake, especially when submerged.

The axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum) and the common frog (Rana temporaria) are classic models: axolotls rely heavily on skin and gill respiration in captivity, while Rana species supplement lung breathing underwater via their skin. Because the surface is so permeable, pollutants, acidification and pathogens penetrate tissues easily, making these animals sensitive sentinels of water quality.

Field studies link pesticide runoff and disease outbreaks to mass mortalities, and conservation assessments show about 40% of amphibian species face threats that often interact with skin sensitivity.

2. Three-Chambered Heart and Circulatory Adaptations

Most amphibians have a heart with two atria and a single ventricle. That three-chambered arrangement suits a dual existence: blood can be routed to skin for cutaneous gas exchange as well as to the lungs and body.

The single ventricle does allow some mixing of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood, but amphibians mitigate inefficiency with timing of contractions, vascular shunts and by using skin respiration when submerged. Because of these features, salamanders are frequently used in university labs that study vertebrate cardiovascular development.

Understanding this circulatory pattern helps veterinarians treat pet frogs and informs comparative studies of how hearts evolved in terrestrial vertebrates.

3. Moist, Glandular Skin: Mucous and Poison Glands

Amphibian skin hosts glands that secrete mucus to maintain hydration and, in many species, toxins for defense. Mucous keeps the surface wet for gas exchange and can limit pathogen attachment.

Poison glands, such as the parotoid glands of toads, produce alkaloids and other compounds that deter predators. Poison dart frogs of the family Dendrobatidae are a striking example: their skin alkaloids are potent enough to discourage or harm would‑be attackers.

Researchers have also mined amphibian skin for potential medicines. For instance, magainins from Xenopus species inspired work on antimicrobial peptides that could inform new antibiotics and wound-healing therapies.

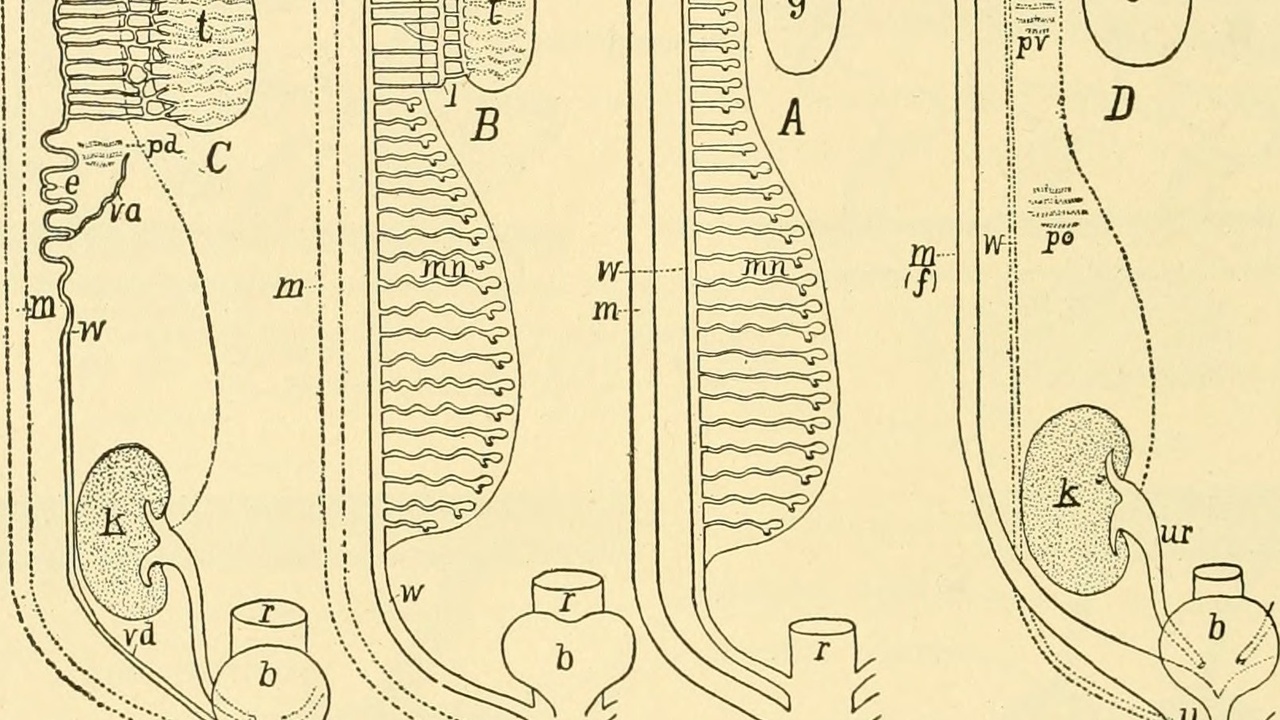

4. Limb Structure and Skull Adaptations Reflecting Early Tetrapods

Amphibian limbs and skulls retain primitive tetrapod traits, a legacy of the transition to land. Many species show a pentadactyl limb plan and a relatively simple skull compared with later vertebrates.

Fossil comparisons to Devonian taxa such as Ichthyostega illustrate these links to the deep past (about 370 million years ago). Modern salamanders often display a sprawling gait and limb posture that echo early tetrapod mechanics.

Comparative anatomy—looking at frog skulls versus salamander skulls—helps paleontologists and developmental biologists trace how feeding, sensory and respiratory structures changed during vertebrate evolution.

Life Cycle & Reproductive Strategies

Many amphibians undergo dramatic life-history shifts from egg to larva to adult, but reproductive tactics vary widely. Some species release eggs in water and leave them, while others guard nests, carry tadpoles, or lay terrestrial eggs that hatch into miniature adults.

Those differences matter for conservation: species with specialized breeding sites or parental care needs are often harder to protect and restore.

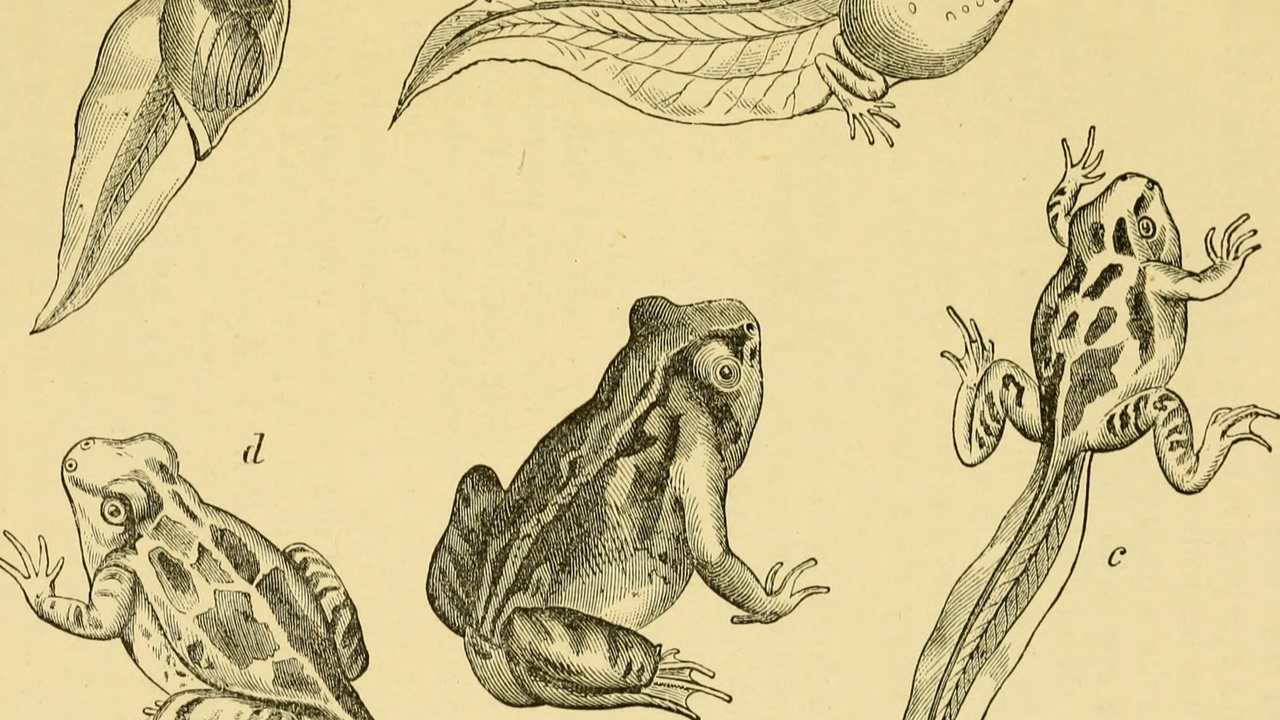

5. Dual Life: Eggs, Larvae (Tadpoles), and Metamorphosis

Many amphibians show a two-stage life cycle: aquatic larvae transform through metamorphosis into terrestrial or semi-terrestrial adults. Typical stages go egg → larva (tadpole) → metamorph → adult.

Timing varies greatly: common frog tadpoles (Rana temporaria) often metamorphose in 6–12 weeks, while some salamanders take months or even years. Others never metamorphose fully; axolotls display neoteny and retain larval traits as breeding adults.

Captive-breeding and husbandry programs rely on precise knowledge of larval timing and cues, because temperature, food and water chemistry influence the schedule and success of metamorphosis.

6. Reproductive Diversity: From External Fertilization to Parental Care

Reproductive strategies among amphibians range from simple external fertilization to complex parental systems. Many frogs spawn eggs in water and males fertilize them externally.

Other groups use internal fertilization; some caecilians and salamanders mate via spermatophores. Parental care can be elaborate: Darwin’s frog broods tadpoles in the male’s vocal sac, while some poison dart frogs carry tadpoles to phytotelmata like bromeliad pools.

And several genera (e.g., Eleutherodactylus) exhibit direct development, where eggs hatch into miniature adults and bypass a free-living aquatic larva altogether—an adaptation to life away from standing water.

Behavioral & Ecological Traits

Behavior and ecology tie amphibian physiology and life history to the environments they occupy. Temperature, moisture and habitat structure shape daily activity, breeding, feeding and survival.

These traits make amphibians both integral to ecosystems and especially vulnerable to human-driven change.

7. Ectothermy: Behavior Driven by Temperature

Amphibians are ectothermic; they depend on external heat sources to regulate metabolic rate. Behaviorally they thermoregulate by basking, seeking cool shade, or shifting activity to night.

Many frogs become active on warm, humid nights—Mediterranean tree frogs, for example, show calling and foraging activity when nocturnal temperatures exceed roughly 15°C. In temperate regions, frogs and salamanders hibernate or overwinter in mud, leaf litter or under stones to survive cold months.

Because ectotherms rely on environmental temperatures, climate change can alter breeding seasons, ranges and predator–prey dynamics for these species.

8. Habitat Ties: Freshwater Dependence and Microclimate Sensitivity

Many amphibians require freshwater habitats for breeding and specific microhabitats for moisture and shelter. Ponds, streams, wetlands and even small vernal pools are critical for reproduction and juvenile development.

Vernal pools, for instance, are essential for wood frogs (Rana sylvatica), while stream-breeding plethodontid salamanders depend on cool, oxygen-rich flow. Loss of those habitats through drainage, pollution or fragmentation is a primary driver of declines; roughly 40% of species are now listed with some level of threat.

Simple conservation actions—protecting wetlands, reducing pesticide use, and creating garden microhabitats like log piles and small ponds—can make a local difference for amphibian populations.

9. Vocalizations and Communication — Especially in Frogs

Many frogs rely on vocal calls to attract mates and defend territories. Calls are species-specific and differ in frequency, duration and pulse rate, which helps individuals identify suitable partners.

Call frequency can be measured in kilohertz: spring peepers call around 3.5 kHz with a rapid, repeated note, while bullfrog vocalizations occupy lower frequencies and longer durations. Acoustic monitoring and citizen-science projects like FrogWatch harness these signals to track populations over time.

Beyond sound, some amphibians also use visual displays and chemical cues during courtship and territorial interactions.

10. Ecological Roles and Conservation Importance

The characteristics of amphibians position them as vital components of ecosystems: they control insect populations, serve as prey for birds, mammals and fish, and act as sensitive indicators of environmental change.

Globally there are about 8,000 amphibian species, and conservation assessments indicate roughly 40% are threatened by habitat loss, pollution, disease (notably chytridiomycosis) and climate shifts. The chytrid fungus drove dramatic declines from the 1980s through the 2000s, prompting captive-breeding efforts for species such as the Wyoming toad.

Protecting wetlands, supporting captive-rearing and reintroduction programs, and participating in monitoring efforts all help buffer these declines and preserve the ecosystem services amphibians provide.

Summary

- Skin is multifunctional: many species exchange oxygen cutaneously, making them sensitive bioindicators of water quality and disease.

- Ancient anatomy meets modern needs: three-chambered hearts, glandular skin and tetrapod-like limbs reflect evolutionary history and diverse lifestyles.

- Life cycles vary from aquatic tadpoles that metamorphose in 6–12 weeks to neotenic and direct-developing species, so conservation must account for varied reproductive needs.

- Behavior and ecology—temperature-driven activity, habitat specificity and species-specific calls—shape how amphibians interact with ecosystems and people.

- Conservation is urgent and actionable: about 8,000 species exist worldwide and roughly 40% are threatened; protecting wetlands, reducing pollutants and joining monitoring programs like FrogWatch are practical steps readers can take.