In 1941 Swiss engineer George de Mestral looked at burrs clinging to his socks under a microscope and invented Velcro — a modern reminder that plants were hitching rides on animals long before humans mimicked them. That burr from burdock (Arctium) is both a literal and metaphorical fastener linking animal movement to plant spread.

Seed movement by animals shapes forests, crops, and restoration projects. Plants rely on birds, mammals, insects and even humans to move seeds away from parents, into new habitats, or into protected microsites. Ecologically, roughly 70–90% of tropical tree species depend on vertebrate ingestion for dispersal, so these interactions matter at landscape scale.

Dispersal modes include endozoochory (seeds carried inside animals), epizoochory (seeds hitching on fur or feathers), and scatter-hoarding (animals caching seeds). Below are ten traits that make seeds successful at getting carried, surviving the trip, and establishing where they land. The piece uses clear examples — blueberries, figs, burdock, and caching jays — to show how form, chemistry and timing work together.

Morphological adaptations that aid transport

Physical form often dictates how a seed interacts with an animal. Some fruits tempt animals to eat and carry seeds internally. Others cling to fur or clothing. Still others protect the embryo during rough transit. These morphological traits connect to disperser identity, travel distance and the microhabitat where a seed ultimately lands.

1. Fleshy, nutritious fruits that attract ingestion

Many plants package seeds inside fleshy fruits so animals will eat them and move the seeds in droppings. Sugars, fats and juicy pulp are direct rewards that increase repeat visits by birds and mammals.

Bird-dispersed fruits often have high soluble sugar (roughly 10–25% in many species) and bright colors, while fatty fruits attract mammals that need energy-rich snacks. Gut passage frequently increases dispersal distance and can, for some species, aid germination.

Examples include blueberries and figs. Ficus species provide fruit year-round for frugivores, and mistletoe berries are swallowed by birds then defecated onto branches where seedlings can establish.

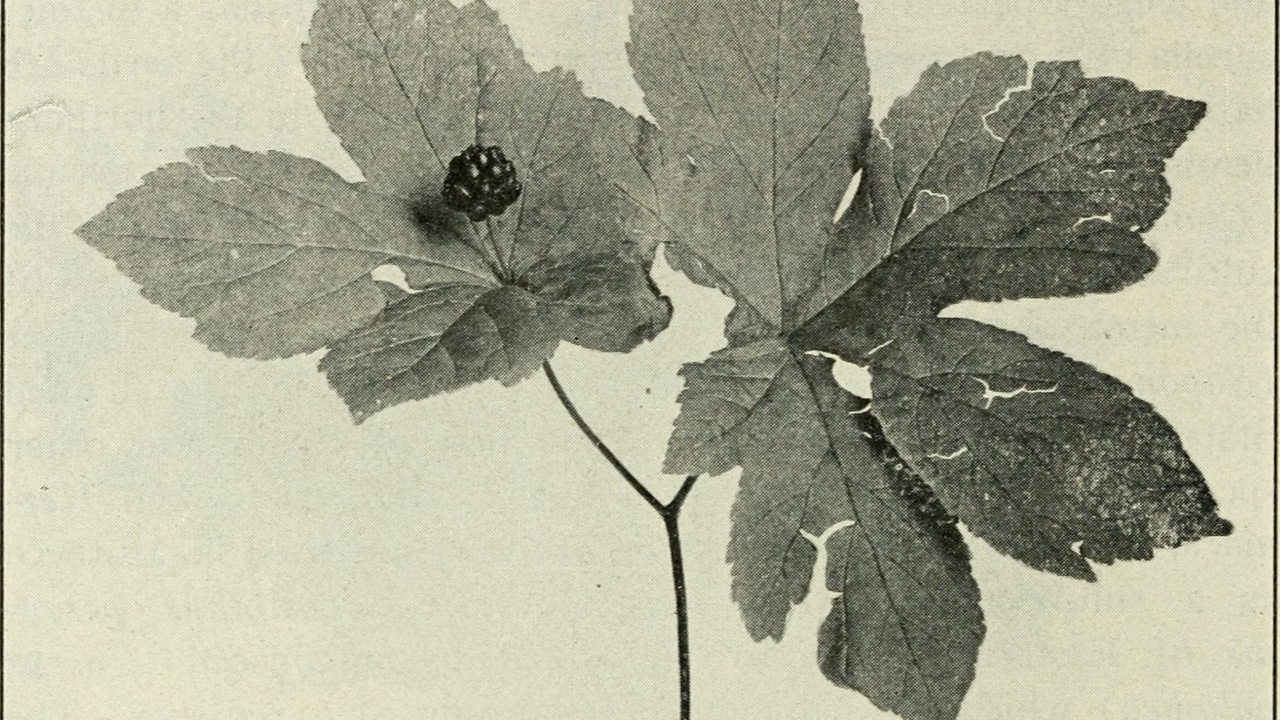

2. Hooks, barbs and sticky coatings for hitchhiking (epizoochory)

Epizoochory relies on external attachment. Hooked awns, barbed burrs and sticky mucilage let seeds cling to fur, feathers or clothing until the animal moves on.

Burdock burrs (Arctium) and cleavers (Galium aparine) are classic examples; burdock famously inspired Velcro after George de Mestral’s 1941 observation. Such seeds can travel from meters to dozens of kilometers depending on host movement and human activity.

The downside is dependency on contact frequency and grooming. If an animal grooms quickly, attachment fails. If animals use narrow trails, seeds move along predictable routes rather than randomly across a landscape.

3. Small, lightweight seeds adapted for ingestion and long-distance travel

Tiny seeds in fleshy fruits suit bird dispersal because they pass through guts intact. Birds, including migratory species, can carry seeds hundreds to thousands of kilometers during seasonal movements.

Seed size often correlates with disperser body size: small passerines take the smallest drupes, larger frugivores swallow bigger fruits. Examples include small-seeded Viburnum and many tropical understory shrubs carried by thrushes and flycatchers.

4. Tough, protective seed coats that survive digestion and abrasion

Hard or impermeable seed coats protect embryos against stomach acids, abrasion in gut tracts, and surface damage during caching or burial. These coats let seeds survive hours to days inside animals, enabling transport by migratory hosts.

Mechanical or chemical scarification during gut passage often weakens the coat and can trigger germination. Legumes, mesquite and many Acacia-type seeds survive ingestion by herbivores and emerge ready to sprout when conditions suit.

The trade-off: greater durability may prolong dormancy and require dormancy-breaking events such as abrasion, heat or microbial attack before germination.

Mutualistic and behavioral traits that improve delivery

Plants don’t work alone. They evolve signals and rewards that match animal preferences, and animals evolve behaviors that incidentally move seeds to good spots. Mutualisms — feeding signals plus animal behavior — greatly boost effective dispersal.

5. Visual and chemical cues (color, scent, and nutrient rewards)

Fruits often advertise to the right audience. Bright reds and blacks target bird vision, while strong odors attract mammals that hunt by scent.

Nutritional profiles also tune dispersers: sugar-rich fruits suit birds and provide quick energy, whereas lipid-rich fruits appeal to mammals. Many bird-dispersed fruits fall in the 10–25% soluble sugar range, which promotes rapid ingestion and repeat visits.

Examples: elderberries and serviceberries draw thrushes and waxwings. Capsicum (chili) fruits use bright color to attract birds while capsaicin deters mammals that might chew seeds.

6. Fruiting phenology and mast seeding to overwhelm predators or ensure disperser visits

Timing matters. Some plants fruit asynchronously to feed frugivores year-round; figs are a classic example. Others synchronize in mast years to swamp seed predators and increase the odds some seeds escape consumption.

Mast cycles are common in oaks, often occurring every 2–5 years. These pulses drive spikes in animal numbers and caching activity, improving seed survival and long-distance movement.

Consequences include altered recruitment patterns, boom-and-bust wildlife dynamics, and windows for large-scale regeneration or invasion depending on context.

7. Structures and traits that encourage caching and burial (scatter-hoarding)

Large-seeded species often entice scatter-hoarders — birds and mammals that bury seeds for later use. High nutrient density and manageable seed size promote hoarding rather than immediate consumption.

Caching protects seeds from surface predators, fire and drought, and places them in buried microsites favorable for germination. Animals thus serve as long-term planters as well as eaters.

Famous examples: Clark’s nutcracker caches thousands of whitebark pine seeds and transports some up to ~32 km. Eurasian jays and squirrels frequently move and bury acorns and hazelnuts across woodlands.

Ecological and physiological traits that enhance establishment

Many characteristics of animal dispersed seeds affect not just movement but survival and recruitment after arrival. Size, chemistry and dormancy responses determine whether a seed sprouts and survives in its new spot.

8. Size and shape tuned to retention, regurgitation, or quick gut passage

Dimensions influence handling. Small round seeds pass quickly through passerine guts, while large seeds may be regurgitated or spat out and end up on branch surfaces or under plants.

Mistletoe seeds, for instance, are sticky and typically end up glued to branches after birds wipe their beaks or regurgitate. That difference changes the microhabitat where seedlings begin life.

Practically, restoration projects often favor bird-dispersed species with small seeds for remote revegetation because birds can deliver seeds to inaccessible areas.

9. Chemical defenses that deter predators but allow mutualists

Secondary compounds help plants choose their partners. Some chemicals make fruits unpalatable to seed-crushing mammals but do not affect birds that swallow seeds whole.

Capsaicin in chilies is a textbook case: it irritates mammals but birds are unaffected, so birds disperse seeds intact. Tannins in acorns reduce palatability and can shift which rodent species handle them and whether they cache them.

These chemical filters shape disperser communities and thus patterns of seed movement and establishment.

10. Dormancy and germination cues triggered by gut passage or burial

Gut passage and burial often act as dormancy-breaking agents. Scarification, exposure to digestive enzymes, or placement in dung or soil can alter seed coat permeability and microbial interactions that promote germination.

Germination responses vary widely by species — improvements can range from modest increases to several-fold gains after animal handling. Legume seeds commonly show higher germination after scarification or gut passage.

Applications include using animal-mediated cues in restoration seeding, and a cautionary note: the same traits that help native recovery also aid invasive spread if dispersers pick up non-native fruits.

Summary

Plants combine form, chemistry and timing to make sure seeds move, survive and sprout where chances are best. Animal behavior — from a bird’s gut to a squirrel’s cache — is as important as the seed’s design.

These characteristics of animal dispersed seeds matter for conservation, restoration and agriculture. Observing local plants and their animal visitors can reveal which strategies are at work and suggest practical actions.

- Physical traits (hooks, flesh, hard coats) determine how seeds get carried and where they land.

- Timing, color, scent and nutrients tune which animals visit and how often; mast years and asynchronous fruiting have outsized ecological effects.

- Caching and gut passage do more than move seeds — they can bury, scarify and fertilize seeds, improving establishment (Clark’s nutcracker and cached pines are a striking example).