In 1818 botanists described Rafflesia arnoldii—the plant with the world’s largest single flower—and were puzzled to find no obvious leaves or stems. Instead, Rafflesia lives almost entirely inside a host vine and blooms only to reproduce, stealing water and carbon through hidden connections. That surprise still shapes how we study parasitic plants: they can rewrite a host’s physiology, alter entire communities, and hit farmers where it hurts. Roughly 4,500 parasitic plant species occur worldwide, spread across about 20 plant families (Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew), and they range from harmless curiosities to major crop pests. This article unpacks eight defining characteristics of parasitic plants and explains why each matters, organized into three groups: biology and morphology; lifecycle and interactions; and ecological and human impacts.

Biology and Morphology

Parasitic plants share anatomical and physiological tweaks that let them tap other plants’ vascular systems. Many of those tweaks center on specialized structures, altered photosynthetic capacity, and sometimes dramatic losses of typical organs. Below are three core morphological traits that recur across root and stem parasites, with species examples and why those traits matter for ecology and agriculture.

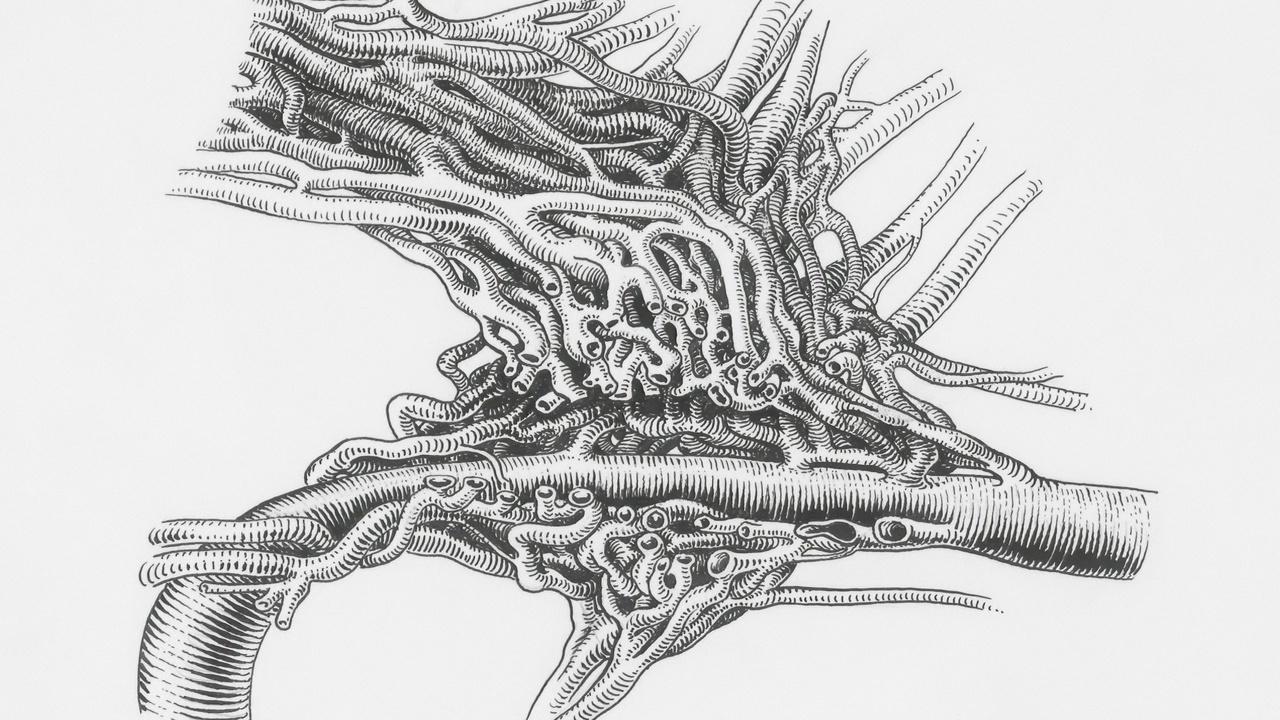

1. Specialized feeding organ: the haustorium

Parasitic plants form a haustorium to tap host xylem and, in some cases, phloem. A haustorium is a modified organ—root- or stem-derived—that penetrates host tissues, establishes intimate cell-to-cell contact, and draws water, minerals, and sometimes sugars from the host.

At the cellular level haustoria produce adhesive cells and cell-wall–degrading enzymes that allow them to breach host barriers and fuse with vascular bundles. Molecular studies show parasite and host exchange signals at the interface, and some parasites even import host RNA and proteins across that bridge.

Functionally this structure is everything: without a haustorium, a parasite can’t siphon resources. Root parasites such as Orobanche and Striga produce root haustoria, while stem parasites like Cuscuta (dodder) form stem haustoria that press into the host stem. Haustorium penetration can form a functional vascular connection within a few days of contact, which helps explain how quickly infestations can take hold.

2. Range from hemiparasites to holoparasites (partial to total dependence)

Parasitic species sit on a spectrum. Hemiparasites retain chlorophyll and perform some photosynthesis while drawing water and minerals from hosts; mistletoes are a familiar example perched on tree branches and visibly green. Holoparasites, by contrast, lack chlorophyll and are entirely dependent on hosts for carbon and nutrients.

That difference matters. Hemiparasites tend to be less selective about hosts and can survive periods with weaker connections, while holoparasites like many Orobanche and Rafflesia species have evolved tighter host-specific links and often a cryptic lifestyle within host tissues. The physiological split also affects detection and control: green hemiparasites are visible, but holoparasites may remain unnoticed until reproduction.

3. Reduction or modification of typical plant organs

Many parasitic plants show dramatic reduction or alteration of leaves, stems, and roots. Cuscuta (dodder), for example, has threadlike, twining stems with scale-like leaves that do little photosynthesis. Broomrapes (Orobanche species) have reduced vegetative structures and appear as short, fleshy shoots near host roots.

These reductions are adaptive: if the parasite gets carbon from a host, investing in large photosynthetic structures is wasteful. The morphological streamlining also complicates identification and early detection in agricultural settings. Rafflesia is extreme—vegetative tissue is virtually absent, and the plant is known mainly for its enormous flower.

Lifecycle and Host Interactions

How parasitic plants find, attach to, and exploit hosts is central to their success and to managing them. Lifecycle stages—dormant seeds, host-detection cues, rapid attachment, and varied host ranges—determine ecological impact and control options. The next four traits explain these dynamics and show why timing often decides whether a crop survives an infestation.

4. Host-detection strategies and chemical cues

Parasitic plants use chemical and physical signals to detect suitable hosts. Root parasites are famously sensitive to strigolactones, a group of host root exudates that trigger seed germination in Orobanche and Striga. Stem parasites rely on volatile organic compounds and touch cues to home in on aerial hosts.

Striga seeds can remain dormant in soil for years and then germinate only when they sense host exudates—this synchronization maximizes their chance of successful attachment. Knowing these cues has practical payoff: farmers and researchers use trap crops, synthetic inhibitors, or signaling analogs to disrupt germination and reduce infestations.

5. Rapid attachment and establishment after contact

Once contact is made, many parasites attach and form functional haustoria quickly to outrun host defenses. Stem parasites like Cuscuta wrap around a stem and begin penetrating within 1–3 days; root parasites form connections shortly after germination, often within a week.

To breach host tissues parasites secrete enzymes and modulate local cell walls, while some suppress or evade host immune responses. This speed explains why early detection matters: by the time you see aboveground signs, the parasite may already be drawing significant resources.

6. Varied host specificity: generalists to specialists

Host range varies widely. Some parasites are specialists tied to one or a few hosts, having co-evolved finely tuned interactions. Others are generalists and will attack many species, including economically important crops.

That variation shapes ecology and management. Specialist parasites can decline if their host disappears, but they also foster close co-evolutionary dynamics. Generalists pose broader agricultural risk: Striga species attack multiple cereals across sub-Saharan Africa and are linked to multi-billion-dollar regional losses, making resistant varieties and crop rotation key management tools.

Ecological Roles and Human Impacts

Parasitic plants are not only pests; they are ecological players that can reshape communities, nutrient flows, and species interactions. Their impacts span negative effects on crops and individual hosts to positive roles as resources for wildlife and drivers of diversity. The last two characteristics highlight those dual roles and the socio-economic stakes involved.

7. Ecosystem engineers: effects on biodiversity and nutrient flows

Some parasitic plants act like ecosystem engineers by weakening dominant hosts and creating space for other species. Partial suppression of a canopy tree, for instance, can increase light and soil resources for understory plants, raising local plant diversity in some systems.

Mistletoe patches are a clear example: their fruits and nectar attract birds and pollinators, boosting local wildlife activity. In Australian woodlands and parts of Africa researchers have documented significant increases in bird visitation and nesting where mistletoe density is high. Those benefits come with trade-offs—hosts suffer reduced vigour and sometimes mortality—so the net effect depends on context.

8. Economic and agricultural impacts (from pests to potential uses)

Parasitic plants can be costly. Striga species, in particular, are associated with annual cereal yield losses that range from roughly 30% to complete crop failure in severe infestations, and regional economic assessments place losses in the order of billions of U.S. dollars across sub-Saharan Africa (FAO and peer-reviewed estimates).

Control options include breeding for resistance, timely herbicide application, push-pull and trap-cropping strategies, and improved soil fertility to reduce host susceptibility. Each approach has limits: resistance can break down, and chemicals may be impractical for smallholders.

On the positive side, some parasitic species have traditional medicinal uses and modern researchers are investigating unique compounds from parasitic-plant interactions. Studies into host-derived signaling and targeted herbicide delivery show promise for smarter control tools that exploit the parasite’s own biology.

Summary

- Parasitic plants rely on a haustorium to tap host xylem and phloem, often forming a vascular connection within days.

- The group spans hemiparasites (partial photosynthesis) to holoparasites (no chlorophyll), a spectrum that shapes detection, evolution, and management.

- Life-history traits—host-detection via chemical cues, rapid attachment, and varied host specificity—determine ecological impact and the difficulty of control.

- Parasitic plants can both support biodiversity (for example, mistletoe-driven bird communities) and cause severe agricultural losses; roughly 4,500 parasitic plant species exist worldwide, and pests like Striga can cut yields by 30–100%.

- Practical takeaway: investing in research, resistant varieties, and farmer outreach on parasite biology offers the best path to reduce crop losses while recognizing the ecological roles some species play.