Desert regions typically receive less than 250 mm of rainfall per year, yet a surprising variety of plants not only survive but thrive there. That contrast matters to gardeners, land managers, and farmers facing hotter, drier climates: choosing the right species cuts irrigation needs, stabilizes soils, and supports wildlife. Xerophytic plants survive in dry environments through a coherent suite of structural, physiological, and reproductive adaptations—here are 8 key characteristics that explain how they conserve water, capture scarce moisture, and reproduce under harsh conditions. Read on for practical insights grouped into structural, water‑storage and uptake, physiological, and reproductive strategies that you can apply to planting, restoration, or low‑water landscaping.

Structural adaptations that reduce water loss

Physical form matters. Many dry‑land plants minimize evaporation and heat load with body shapes, surface coatings, and leaf alterations that cut the area exposed to sun and wind. These visible traits appear in familiar species such as cacti, agave, and aloe, and they’re useful indicators when selecting plants for gardens or restoration projects.

1. Thick, waxy cuticle and reduced leaf surface area

Many xerophytes have a thick, waxy cuticle and often small or absent leaves to limit evaporative surface. With annual rainfall under 250 mm in deserts, a robust epidermal coating makes a big difference: the cuticle acts as a barrier to water vapor, slowing transpiration after rainfall. Botanists measure cuticle thickness to compare species—textbooks and field guides report wide variation, so consult them for specifics on particular genera. In practice, that’s why houseplants like Aloe vera and outdoor agaves need less frequent watering: water is stored behind a tough, water‑tight skin. In cacti such as the saguaro, leaves are replaced by green, photosynthetic stems that perform gas exchange while keeping surface area low.

2. Leaf modification: spines, hairs, and rolled leaves

Leaves are often transformed into spines, covered with hairs (trichomes), or rolled inward to cut transpiration and deter herbivores. Spines greatly reduce exposed surface area and cast tiny shadows that lower tissue temperature; trichomes trap a thin layer of still air that slows evaporation. Some grasses roll their blades so only a narrow strip exchanges gases during drought. These features affect plant selection for xeriscaping and erosion control because they influence water loss, light reflection, and how animals use a site. For example, Opuntia pads bear dense spines, many desert shrubs show tomentose (hairy) leaves, and rolled leaves are common in arid grasses. Field measurements show leaf pubescence can reduce leaf temperature by several degrees, improving water economy (see regional field studies for values).

Water storage and uptake strategies

Xerophytes combine internal water tanks with specialized root systems. Succulence stores liquid for drought spells, while root architecture either seeks deep water or quickly captures brief surface moisture. Both strategies guide horticulture and restoration choices.

3. Succulence: specialized water-storing tissues

Succulence means storing water in stems, leaves, or roots so a plant can ride out dry periods. Many succulents—prominent in families like Cactaceae (about 1,750 species) and Crassulaceae—hold enough water to survive weeks or months without rain. That storage lets species such as barrel cacti, saguaro, Aloe vera, and agave maintain metabolism during drought. For gardeners, succulents translate into low‑frequency irrigation and resilience in hot summers. Farmers and restoration practitioners also use succulents (Aloe, Agave) in low‑water systems and living fences where seasonal dryness is predictable.

4. Root strategies: deep taproots and widespread surface roots

Root form matches water availability. Phreatophytes send deep taproots down to groundwater, while other species deploy broad, shallow root mats to capture fleeting rain. Prosopis (mesquite) species are famous for very deep roots—studies report roots reaching tens of meters in search of water—whereas many cacti and succulents have dense lateral roots that quickly absorb surface moisture. Restoration planners choose deep‑rooted species where groundwater is accessible and shallow‑rooted types for sites that rely on episodic rains.

Physiological adaptations for water-use efficiency

Beyond shape and storage, plants adjust when and how they exchange gases. Altered photosynthetic pathways and stomatal behavior let some species fix carbon while cutting daytime water loss—traits of interest for breeding drought‑tolerant crops.

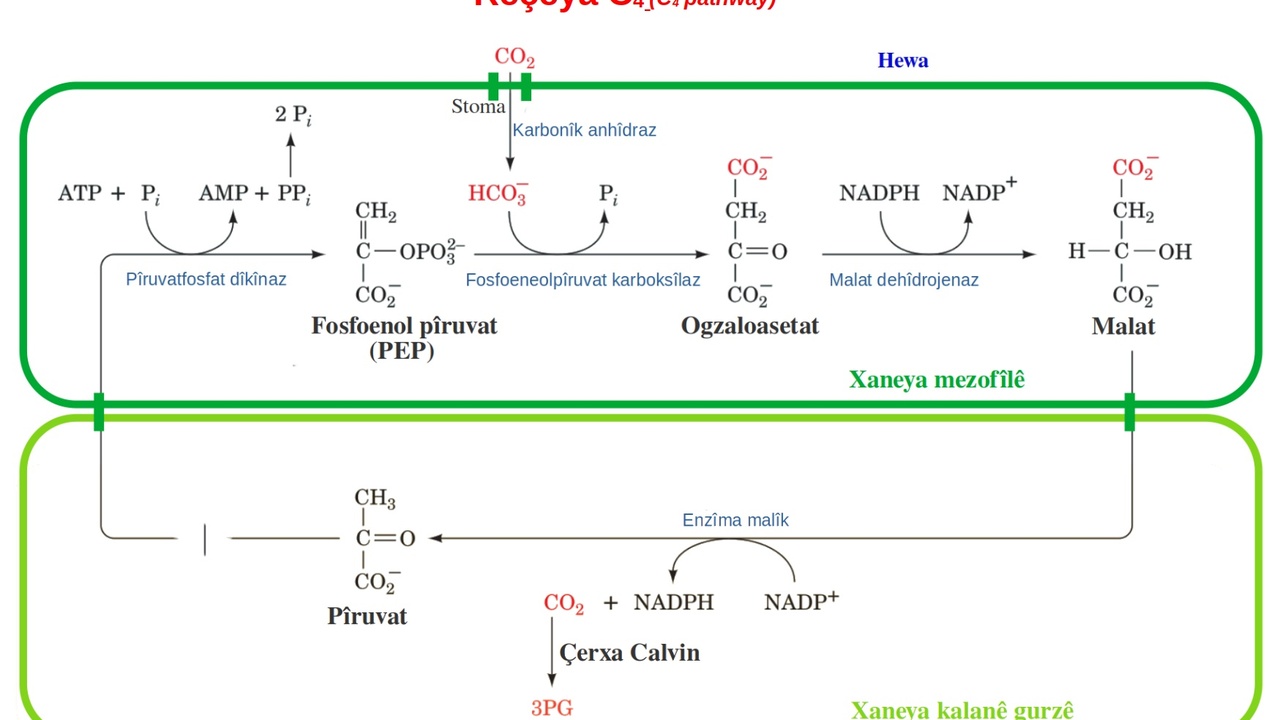

5. CAM and C4 photosynthesis: timing and efficiency

Some xerophytes use CAM (Crassulacean Acid Metabolism) or C4 photosynthesis to boost water‑use efficiency. CAM plants open stomata at night to take up CO2 and store it as organic acids, then photosynthesize during the day with stomata closed—this timing cuts daytime transpiration. CAM is common among succulents and certain bromeliads and orchids; pineapple and many agaves are CAM users, which helps explain their drought tolerance. Although CAM represents a small fraction of all vascular plants, it’s ecologically significant in arid and semi‑arid zones. Plant physiologists often cite CAM as a model for improving crop water efficiency in dry regions.

6. Stomatal control, low stomatal density, and nocturnal opening

Stomata—the tiny pores that control gas exchange—are fewer, sunken, or rhythmically timed in many dry‑adapted species. Fewer stomata or recessed pores slow water loss; in CAM plants, stomata open at night when air is cooler and humidity is higher. Comparative measurements show xeric species can exhibit markedly lower stomatal conductance than mesic relatives, meaning less water is lost per unit leaf area. These traits inform greenhouse watering schedules and choices for low‑water crops where nighttime cooling and ventilations matter.

Reproductive and life-history strategies for dry environments

Reproduction in deserts is about timing and patience. Some plants race through their life cycle when water appears; others rely on long‑lived seeds that wait for the right moment. Both approaches maintain populations across unpredictable seasons.

7. Rapid life cycles and opportunistic germination

Many desert annuals are opportunists: seeds germinate after rain, grow fast, flower, and set seed within weeks. Germination cues often combine soil moisture and temperature, and some species complete their life cycle in as little as four to six weeks after sufficient rain. Plants like sand verbena and many desert wildflowers exploit these windows. Restoration practitioners use knowledge of these timing cues to schedule sowing for optimal establishment after seasonal rains.

8. Seed dormancy, protective seed coats, and specialized dispersal

Long‑lived seed banks let populations endure drought years. Seeds with hard coats or physiological dormancy can remain viable for years or even decades until conditions are right—research documents dormancies spanning multiple seasons to decades in some arid species. Dispersal strategies (wind, ants, rodents) also shape where plants establish and how they escape seed predators. Restoration programs often rely on seed mixes that include species with persistent seed banks and known dormancy traits to ensure regeneration after rare rain events.

Summary

Plants adapted to dry places balance structural defenses, water storage and uptake, physiological economy, and reproductive timing. Thick cuticles, spines, and reduced leaves cut water loss; succulence and strategic roots store and fetch moisture; CAM and stomatal strategies squeeze more carbon from each liter of water; and flexible life histories—rapid annuals or seeds that wait—keep populations persistent. Those patterns point to practical choices for gardening and restoration: pick succulents like Aloe vera or Opuntia for low‑care beds, use deep‑rooted natives where groundwater is available, and include opportunistic annuals in seed mixes to take advantage of episodic rains. If you’re involved in habitat recovery, contact local native‑plant societies or seed banks to match species to local moisture regimes.

- Structural traits (waxy cuticles, spines) reduce evaporation and heat stress.

- Succulence and root architecture provide complementary storage and uptake strategies.

- CAM photosynthesis and stomatal timing improve water‑use efficiency in many succulents.

- Life‑history tactics—fast annuals and persistent seed banks—match reproduction to unpredictable rains.

- Try drought‑tolerant, easy plants such as Aloe vera or Opuntia, and consult local native‑plant resources for restoration projects.