In the 18th century, early botanists like Carl Linnaeus used leaf retention and timing of leaf drop to help classify plant groups — a practice that still shapes how we describe evergreen and deciduous species today. Leaf retention matters because it changes when and how a plant captures light, cycles nutrients, and creates habitat: it affects shade in summer, timber quality for industry, carbon timing in forests, and choices gardeners make about screening and seasonal color.

Put simply: evergreens keep foliage year-round (or for multiple years), while deciduous plants drop most of their leaves each year and regrow them when conditions favor growth. This article groups ten core differences into three accessible categories — Morphology & Physiology; Ecology & Phenology; Human Uses & Management — so you can quickly see how form, function, and practical choices line up.

Deciduous leaves typically live less than one year, while some evergreen needles can last 2–15 years (pines 2–5 years, spruces 4–7 years, some firs up to 10–15 years), and those lifespans drive many of the trade-offs discussed below.

Morphology & Physiology

This category focuses on physical form and internal function: how leaves, buds, and photosynthetic systems differ and why that matters for water economy, nutrient use, and seasonal timing. Evergreens tend to invest in tougher, longer-lived foliage with traits that reduce water loss — thicker cuticles, sunken stomata, and lower stomatal density in many needle-leaf species — whereas deciduous broadleaves favor high surface area and higher stomatal densities to maximize short-term carbon gain. Those anatomical differences change where species do well: needle-leaf evergreens often dominate cold or dry sites because their structure limits desiccation, while broadleaf deciduous trees excel where a shorter, intense growing season rewards rapid photosynthesis. Below are four specific physiological contrasts that explain these patterns and their practical implications for gardeners and land managers.

1. Leaf retention and lifespan

Deciduous plants shed leaves on an annual cycle; most deciduous leaves live less than one year. Evergreens retain foliage for multiple years — needles commonly persist 2–15 years depending on species — which spreads the construction cost of leaves over time.

The trade-off is simple: deciduous species pay the metabolic cost of producing new, high-performance leaves each spring to maximize photosynthesis during a defined season, while evergreens conserve nutrients by keeping leaves longer but accepting lower average photosynthetic rates per leaf.

Real-world impact: a sugar maple (Acer saccharum) forms a full canopy each spring and drops it every autumn, altering seasonal shade; eastern white pine (Pinus strobus) holds needles for several years, providing steadier year-round cover.

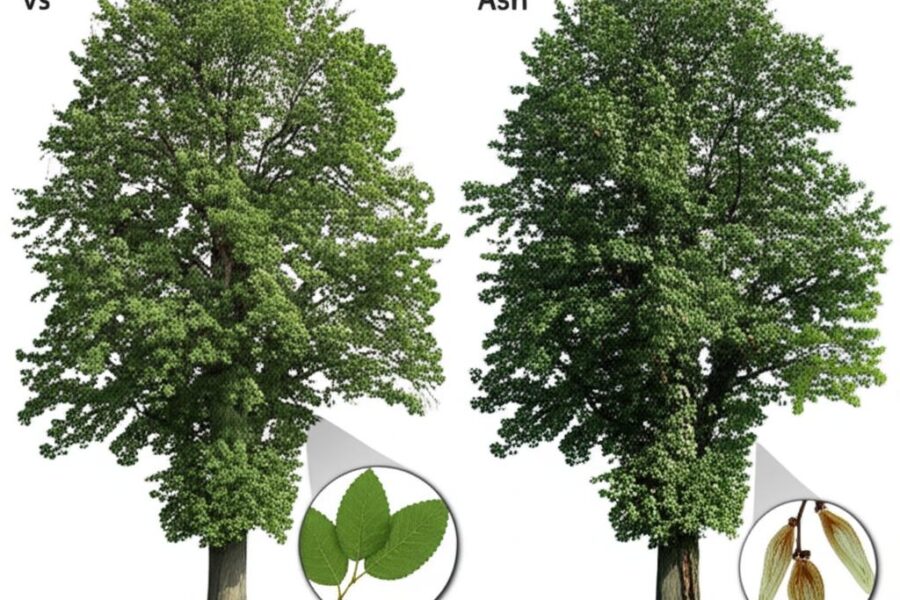

2. Leaf structure and anatomy

Structural contrast is obvious: deciduous trees usually have broad, thin leaves while many evergreens carry needles or scale-like leaves. Broad leaves increase surface area for light capture but raise transpiration loss; needles reduce surface area-to-volume ratio and often have a thicker cuticle and sunken stomata to limit water loss.

Quantifiable trends: needle-leaf species typically show lower stomatal density and higher leaf mass per area (LMA) than seasonal broadleaves, reflecting investment in tougher tissue. That anatomy makes needle-leaf evergreens more common in cold, dry, or nutrient-poor sites where conserving water and nutrients matters more than peak instantaneous photosynthesis.

Examples: pine needles with sunken stomata and a waxy cuticle tolerate winter desiccation; oaks and other deciduous broadleaves have thin blades that capture a lot of light during a short growing season.

3. Photosynthetic timing and efficiency

Deciduous species concentrate photosynthesis into a relatively short, high-intensity season: leaves “flush” in spring and reach peak rates within weeks. Many evergreens photosynthesize at low to moderate rates year-round, including during cool months when broadleaves are absent.

At the leaf level, deciduous trees often allocate more nitrogen per unit leaf area to enzymes that boost peak photosynthetic capacity, while evergreen leaves have lower nitrogen concentration but longer functional life. The result is a carbon-capture strategy of fast, seasonal gains versus steadier, longer-term returns.

Application: if your goal is rapid carbon uptake on a short rotation, fast-growing deciduous species can be efficient; if you need year-round shading or shelter, evergreens maintain canopy function in shoulder seasons.

4. Bud protection and dormancy

Deciduous trees form visible winter buds that protect next season’s leaves and flowers; those buds are insulated by scales and often triggered by chilling hours and photoperiod. Many evergreens rely on tissues and chemistry that resist freeze-thaw cycles without a complete loss of foliage — resin, antifreeze sugars, and more compact buds help tolerate cold.

Quantitatively, hardy bud survival often tracks minimum winter temperatures for a region (for example, many temperate maples survive down to −30°C in their coldest-adapted populations, while some conifers persist at similar or lower extremes thanks to biochemical protections).

Practical effect: frost sensitivity and appropriate planting timing differ — delay planting tender evergreens until soils are stable, and choose species with proven bud hardiness for your USDA zone.

Ecology & Phenology

Leaf retention and timing shape ecosystem processes such as nutrient cycling, habitat seasonality, and where species can persist across climates. Deciduous leaf-out and litterfall create strong seasonal pulses that feed soil microbes and herbivores; evergreen dominance in boreal and montane zones shapes slower nutrient turnover and year-round cover.

To frame this ecologically: differences between evergreen and deciduous plants influence phenology windows, soil chemistry, and biome distributions — from temperate deciduous forests (commonly between roughly 30°–50° latitude in the Northern Hemisphere) to boreal evergreen belts that extend across higher latitudes.

5. Seasonal timing and phenology

Deciduous species show pronounced seasonal cues: leaf-out in spring and leaf drop in autumn. Growing-season length can differ by 2–4 months between regions and between deciduous-dominated and evergreen-dominated stands.

Those seasonal windows matter for animals and plants. Spring ephemerals, for instance, complete their life cycle in the brief period before a deciduous canopy closes, while many insects and pollinators time reproduction to leaf- and flower-out dates.

Evergreen phenology is more muted; some evergreens show subtle seasonal adjustments in photosynthetic rate or new shoot growth, but they provide continuous structural habitat and winter shelter for wildlife.

6. Nutrient cycling and soil interactions

Deciduous leaf drop supplies a large seasonal pulse of litter that typically decomposes relatively quickly — in many temperate systems a significant portion of leaf litter can break down within a single year — returning nitrogen and other nutrients to the soil.

By contrast, evergreen needle litter decomposes more slowly and often contains higher lignin and resin compounds, which can acidify soils and slow nutrient release. That difference affects understory composition and fertility: deciduous stands tend to have richer, faster-cycling soils; evergreen stands often have thinner, more acidic organic layers.

Management tip: gardeners and foresters often amend soils under dense pines or use mulches and targeted fertilization to offset slower nutrient return in evergreen-dominated sites.

7. Climate distribution and resilience

At broad scales, evergreen conifers dominate boreal forests and many montane belts, while temperate deciduous broadleaf forests (oaks, maples, beeches) are common roughly between 30° and 50° N latitude. These distributions reflect strategies: evergreens tolerate nutrient-poor soils, cold, and shorter growing seasons; deciduous species avoid winter stress by dropping leaves.

Under drought or warming, vulnerabilities shift. Evergreens can be drought-tolerant when their anatomy conserves water, but some conifers suffer from bark beetles and heat stress. Deciduous trees may gain range under warmer winters but can be exposed to late-spring frost damage if phenology advances too quickly.

Practical takeaway: mix species and functional types where feasible to hedge bets against changing conditions and pest outbreaks.

Human Uses & Management

Biological differences translate directly into practical choices for landscaping, timber production, and carbon management. Deciduous trees often provide seasonal aesthetics and hardwood products, while evergreens give year-round screening and are commonly used for construction softwoods.

Managers should weigh rotation age, wood density, and ecosystem services: typical rotation ages range from about 30 years for fast-growing plantation pines to 80+ years for high-quality hardwoods like oak used in cabinetry. Those numbers influence whether you prioritize quick sequestration or long-term biomass stores.

8. Landscaping, aesthetics, and functional uses

Gardeners and planners use deciduous trees for seasonal color and afternoon shade; evergreens are chosen for winter screening, windbreaks, and privacy hedges. Place evergreens upwind to serve as year-round shelter; put high-canopy deciduous trees on the south or west side to maximize summer shade while letting winter sun through.

Numeric guidance: common evergreen hedges like Thuja or Leylandii are often planted to final heights of 2–4 m (6–12 ft) for privacy; canopy cover differences vary by species but deciduous trees can cast 50–80% shade in summer at maturity.

Species suggestions: arborvitae (Thuja spp.) and boxwood for year-round screens; sugar maple (Acer saccharum) or London plane (Platanus × acerifolia) for large temperate shade trees and autumn color.

9. Timber, fuelwood, and economic uses

Deciduous hardwoods and evergreen softwoods serve different markets. Hardwoods like oak and maple have higher wood density and are preferred for furniture, flooring, and specialty uses; softwoods such as pine and spruce are widely used for framing, pulp, and general construction.

Rotation ages: plantation pines for lumber are commonly harvested at 30–40 years, while quality hardwoods may be managed on 50–80+ year rotations. Average wood density ranges widely — hardwoods often exceed 600–800 kg/m3, while many softwoods fall between 350–550 kg/m3 — which affects economic value and fuelwood characteristics.

Regional note: in many temperate regions, pine plantations underpin local industries, while broadleaf hardwoods support specialty woodworking economies.

10. Carbon storage and forestry management implications

Life-history strategies shape carbon dynamics. Deciduous plantations with fast-growing species can sequester carbon rapidly in early decades, while old-growth evergreen stands often hold larger standing biomass and soil carbon pools that persist over centuries.

Quantifiable point: short-rotation deciduous plantations may sequester a lot of carbon per hectare in 10–30 years, but long-lived conifer stands often store greater total biomass and long-term carbon in woody tissue and organic soils.

Recommendation for managers: favor mixed-species plantings where possible — combining fast-growing deciduous species for near-term sequestration with evergreen conifers for long-term storage improves resilience and diversifies ecosystem services.

Summary

- Leaf lifespan differs dramatically: most deciduous leaves live <1 year while evergreen needles can last 2–15 years, affecting nutrient use and seasonal cover.

- Structural traits — broad thin leaves vs needles/scales, cuticle thickness, and stomatal placement — drive water economy, cold tolerance, and habitat preference.

- Ecological outcomes include faster nutrient cycling and pronounced seasonal windows in deciduous forests versus slower decomposition, soil acidification risk, and year-round structure in evergreen stands.

- Practical guidance: match species to goals — choose deciduous trees for seasonal shade, autumn color, or fast sequestration; use evergreens for year-round screening, long-term biomass storage, or nutrient-poor sites; consider mixed plantings and consult local extension/forestry services (check USDA hardiness zones) for site-specific recommendations.