Around 25% of all marine species rely on coral reefs — and scientists estimate that hundreds of reef systems have lost half or more of their coral cover over recent decades.

These ecosystems matter for food, coastal protection, biodiversity and cultural identity for millions of people. Understanding the facts about coral reef decline helps explain what’s driving losses and what can be done to protect communities and wildlife.

This article presents eight essential facts organized into three categories: causes; consequences for ecosystems and people; and monitoring, recovery, and policy responses. Each point uses real-world examples — including the 2016–2017 global bleaching events — to show why reefs are vulnerable and what realistic actions exist to slow or reverse damage.

Causes of Coral Reef Decline

Reef loss stems from interacting global and local stressors: rising ocean temperatures, changing seawater chemistry from CO2, and human impacts such as overfishing, land runoff and coastal development. These drivers compound one another, and many reefs have experienced dramatic declines since the mid-20th century.

1. Ocean warming drives mass coral bleaching

Rising sea temperatures force corals to expel the tiny algae (Symbiodiniaceae) that provide most of their energy, producing the pale, stressed condition known as bleaching.

Mass bleaching has become more frequent and severe: global events in 2016 and 2017 caused widespread mortality on the Great Barrier Reef and across Caribbean reefs. In extreme episodes, some areas lost more than 50% of live coral cover over a few years.

The ecological effects are immediate and cascading — fewer habitats for reef fish, lost income for tourism and fisheries, and a much slower recovery trajectory for affected reefs. The northern Great Barrier Reef’s multi-year bleaching in 2016–2017 is a stark example of how repeated heat stress undermines recovery.

2. Ocean acidification weakens coral skeletons

As atmospheric CO2 rises, more CO2 dissolves in seawater and shifts carbonate chemistry toward greater acidity, reducing the availability of carbonate ions corals need to build calcium carbonate skeletons.

Pre-industrial atmospheric CO2 was about 280 ppm; it has climbed past 410 ppm in recent years, and surface ocean pH trends show measurable declines. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and NOAA report that acidification slows calcification and leads to thinner, weaker skeletons.

Weaker skeletons mean slower growth, increased breakage during storms, and lower resilience to other stressors such as disease and bleaching — especially where warming and acidification act together.

3. Local stressors amplify global threats

Local human activities make reefs far less able to cope with climate pressures. Overfishing removes herbivores that keep algae in check, allowing algal overgrowth that blocks coral recruitment.

Land-based runoff — nutrients from agriculture and sewage, plus sediments from erosion — smothers corals and reduces light needed for their symbionts. Physical damage from dredging, coastal construction and destructive fishing compounds decline.

Studies repeatedly show poorer reef condition near poorly managed coasts. Where herbivore biomass falls and runoff increases, coral cover and recruitment rates typically decline, reducing both biodiversity and fisheries productivity.

Consequences for Ecosystems and People

When corals decline, the effects extend beyond reefs themselves to coastal communities, economies and national security in some regions. The following points show how biodiversity, food security and shoreline protection are all at risk.

4. Biodiversity loss and species declines

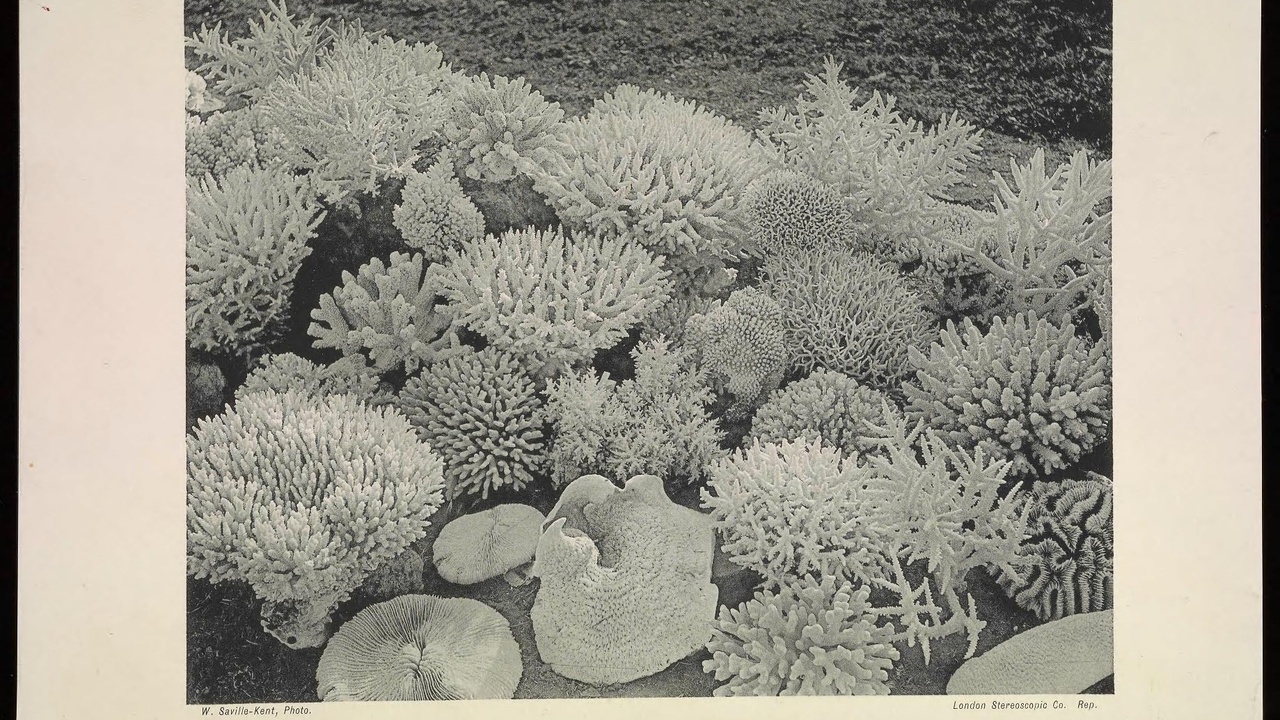

Coral reefs are biodiversity hotspots: they support roughly 25% of marine species despite covering under 1% of the ocean floor.

Many reef species are specialists that rely on live coral for food, shelter or breeding habitat. When coral cover collapses, those species decline first, triggering cascading changes across food webs and ecosystem functions.

After severe bleaching or disease outbreaks, researchers have documented local extirpations of reef fish and invertebrates and a shift toward algal-dominated communities that support fewer species and altered ecosystem services.

5. Threats to food security and fisheries

Reef fisheries provide food and income for an estimated 500 million people, with especially high dependence in parts of Southeast Asia, the Pacific and the Caribbean.

As reefs lose structure and productivity, catches of key reef species fall. Fishers must travel farther or switch gears, increasing costs and food insecurity for coastal households that rely on small-scale reef fisheries for protein and livelihoods.

In several Southeast Asian communities, declines in reef-dependent catches have prompted shifts to alternative livelihoods and heightened vulnerability to economic shocks.

6. Loss of coastal protection and economic value

Coral reefs act as natural breakwaters, attenuating wave energy and reducing coastal erosion and storm damage. Depending on reef morphology, healthy reefs can reduce wave energy by large amounts — in some reef types measurements show attenuation up to about 90–97%.

When reefs degrade, shorelines become more exposed. That raises costs for coastal infrastructure repairs, beach nourishment and emergency response, and it can cut tourism revenue in reef-dependent destinations.

Countries and regions that depend heavily on reef tourism have already documented declines in visitor numbers and associated income following major bleaching events, underlining the real economic stakes of reef loss.

Monitoring, Recovery, and Policy Responses

There are reasons for cautious optimism: scientists and managers are improving monitoring, trying restoration at scale, and designing policy tools that boost resilience. But restoration and protection have limits if warming and acidification continue unchecked.

7. Restoration: what’s possible and what’s limited

Active restoration can help local reefs recover faster, but it’s not a replacement for addressing climate change. Common methods include coral gardening (growing fragments in nurseries), microfragmentation to speed growth, and larval reseeding to increase genetic diversity.

Organizations such as the Coral Restoration Foundation have outplanted thousands of fragments in Florida and the Caribbean, and research teams on the Great Barrier Reef and elsewhere are piloting scaled trials that target hectares rather than square meters.

These efforts show measurable local successes, but they face limits: high per-hectare costs, logistical complexity, and the reality that outplanted corals remain vulnerable to future mass bleaching unless greenhouse gas emissions are reduced.

8. Policy, protection, and the need for climate action

Policy tools — effective marine protected areas (MPAs), fisheries management, pollution controls and coastal planning — increase reef resilience by reducing local stressors.

Roughly 30% of global reefs fall within designated MPAs, but many protected areas lack adequate enforcement or complementary fisheries and land-use measures. Strong local governance matters for outcomes.

International frameworks shape the long-term fate of reefs: IPCC assessments, the Paris Agreement’s emissions pathways, and the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2021–2030) all emphasize that rapid, deep cuts in emissions are essential. Under high-emissions scenarios, many reefs could be functionally lost by the end of this century.

Summary

- Climate-driven warming and ocean acidification are the primary global drivers that undermine coral growth, resilience and recovery.

- Local pressures — overfishing, pollution and coastal development — amplify damage and make reefs far less able to bounce back after bleaching or storms.

- Coral declines threaten biodiversity (about 25% of marine species), food security for roughly 500 million people, and natural coastal defenses that reduce storm impacts and support tourism.

- Restoration (coral gardening, microfragmentation, larval reseeding) offers useful local gains (examples include Coral Restoration Foundation projects), but it is costly and vulnerable to repeated heat events.

- Long-term survival of reefs depends on coordinated local management (effective MPAs, fisheries rules and pollution control) paired with rapid global emission reductions in line with IPCC and Paris Agreement goals; readers can support practical measures by choosing sustainable seafood, backing protected areas and reputable organizations such as NOAA, IUCN and UNEP.