A 19th-century naturalist watching a small, membraned rodent glide between pines called it “one of nature’s little parachutists” — an apt image that still captures why flying squirrels fascinate observers today.

If you enjoy backyard wildlife, care about forest health, or simply love clever animal designs, these animals reward a closer look: they link treetop food webs, help spread fungal networks, and inspire engineers interested in small aerial robots. Flying squirrels combine specialized anatomy, nocturnal behavior, and ecological roles that make them uniquely adapted gliding mammals — and understanding their key characteristics reveals how they move, feed, socialize, and survive in treetops.

Below are eight defining traits — from the patagium that makes gliding possible to sensory adaptations, ecological functions, and conservation concerns — with concrete examples and numbers where researchers have measured them.

Physical adaptations for gliding

1. Patagium: a specialized gliding membrane

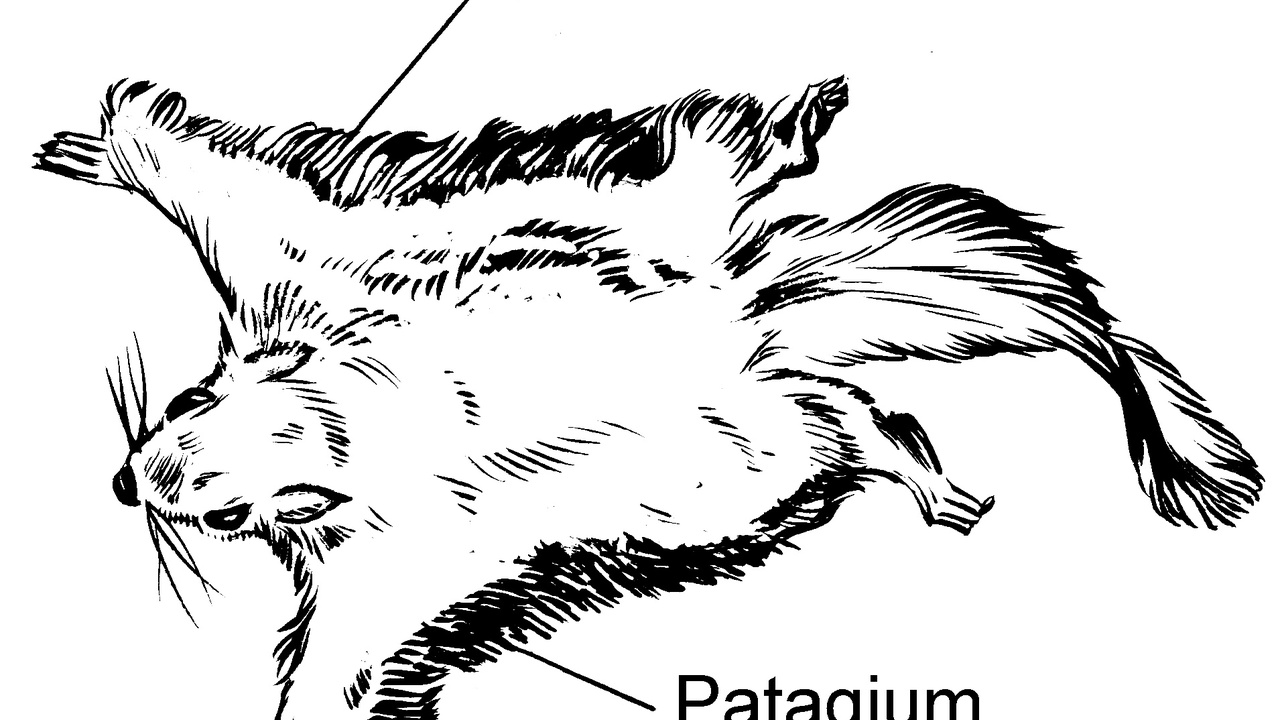

The patagium is the defining gliding surface: a sheet of skin and fur stretched between the forelimbs and hindlimbs that creates lift and control in the air. Muscles along the limb margins and specialized skin allow subtle shape changes that smooth airflow; the fur along the leading and trailing edges also helps reduce turbulence.

Researchers often measure the patagium’s surface area relative to body size because that ratio predicts glide performance. Small North American species such as Glaucomys volans typically have proportionally smaller patagia than giant Petaurista species, and that difference helps explain why Glaucomys glides commonly 10–25 meters while giant flying squirrels may cover 70–100 meters in a single glide.

In practice, a larger patagium increases lift and reduces sink rate, letting animals cross wider canopy gaps with less energetic cost than dropping and re-climbing trees.

2. Tail and steering mechanisms

The tail acts much like a rudder: flattened and often bushy, it provides pitch and yaw control and helps brake at touchdown. By rotating or spreading the tail, a glider modifies airflow and changes its angle of attack in the last half-second of a glide.

Field video analyses show that small gliders make fine tail adjustments during the final 0.5–1.0 seconds before landing, improving accuracy enough to use narrow trunk or branch landings rather than broad limbs. Tail length commonly matches or exceeds the head–body length in many species, which gives designers of biomimetic gliders a clear lesson in balancing surface area for control.

Good steering reduces impact forces and the chance of mislandings, letting gliders exploit perch types that less maneuverable animals avoid.

3. Limb, digit, and skeletal specializations

Launch and landing depend on limbs built for both power and grip. Flying squirrels have relatively long forelimbs, flexible shoulder joints that permit wide limb extension, and strongly curved claws for locking onto bark at takeoff or touchdown.

Skeletal traits also help: reinforced limb bone geometry and shock-absorbing joints reduce landing stresses. Observational studies report typical launch angles in the 30–45° range, allowing a controlled conversion of horizontal speed into lift during the initial glide phase.

Compared with non-gliding tree squirrels, wrist rotation and limb extension patterns differ noticeably, giving glide-adapted squirrels quick, repeatable launches from thin branches in complex canopy environments.

Sensory, behavioral, and ecological traits

4. Nocturnality: vision and sensory adaptations

Most species are nocturnal canopy specialists. Large eyes gather light, retinal specializations increase sensitivity in low illumination, and whiskers provide close-range spatial cues when sight is limited. Acute hearing helps detect predators and vocal signals from conspecifics.

Camera-trap and radio-telemetry studies often record peak activity during the early night hours; many populations show major movement bouts between roughly 20:00 and 02:00 local time and remain active for 4–8 hours each night. These adaptations let gliders exploit food resources while avoiding many diurnal competitors and predators.

5. Diet and foraging flexibility

Flying squirrels are generally omnivorous and opportunistic. Their diet includes seeds, nuts, fruits, insects, bird eggs, sap, and fungi — notably subterranean mycorrhizal truffles that are important in some northern populations.

In parts of North America, studies show truffles or other fungal material can compose 30–60% of the winter diet for northern species such as Glaucomys sabrinus. By consuming and dispersing truffle spores, these squirrels link trees to underground fungal networks that aid seedling establishment and overall forest health.

Seasonal shifts are common: insects and fruits rise in importance during spring and summer, while cached nuts and fungi sustain animals in colder months.

6. Social structure, nesting, and thermoregulation

Social behavior is flexible. Many flying squirrels nest in tree cavities, but they also use dreys (leaf nests) and artificial boxes. Communal nesting is widespread in colder seasons: field studies report clusters typically ranging from 2 to 10 individuals sharing a cavity to conserve heat.

Communal roosting raises juvenile survival and lowers energetic costs in winter. Researchers and citizen scientists often monitor populations with nest boxes, which can provide useful data on reproduction, group size, and seasonal occupancy.

Performance, ecosystem roles, and conservation

7. Gliding mechanics and measurable performance

Flying squirrels are efficient gliders with quantifiable performance. Small species routinely glide 10–25 meters, while larger species have documented glides of 70–100 meters or more; some reports for giant gliders exceed 150 meters under ideal conditions.

Glide angle (the ratio of vertical drop to horizontal distance) typically falls in the 20–40° range, depending on species and launch height. Gliding saves energy compared with repeatedly descending and climbing trunks: a single long glide can avoid the cost of several vertical climbs.

Engineers study glide mechanics and control strategies from these animals to inform small UAV design and deployable membrane wings for drones and robotics, drawing lessons from patagium shaping and tail-based steering.

8. Conservation status and human impacts

There are roughly 50 species of flying squirrels worldwide, with the greatest diversity in Asia. Many species are listed as Least Concern, but several island endemics and populations tied to old-growth forests are Vulnerable or Endangered on the IUCN Red List.

Main threats include habitat loss and fragmentation, which break canopy continuity and reduce safe glide corridors, vehicle collisions near forest edges, and introduced predators on islands. For example, population declines for some forest-dependent species track the loss of contiguous old-growth habitat in parts of their range.

Conservation actions that help include protecting canopy corridors, retaining cavity trees, installing and monitoring nest boxes, and maintaining fungal-rich forest floors. Local programs that preserve riparian and canopy linkages often yield measurable gains in occupancy and breeding success for glide-adapted squirrels.

Summary

Key takeaways about the characteristics of flying squirrels and why they matter:

- Specialized anatomy — a patagium, a maneuverable tail, and flexible limbs — allows efficient, controlled glides that save energy and expand habitat use.

- Nocturnal sensory adaptations and an opportunistic diet (fungi, seeds, insects) link flying squirrels to forest regeneration and mycorrhizal networks.

- Communal nesting and cavity use (groups commonly 2–10) aid thermoregulation and juvenile survival; nest boxes provide valuable monitoring and conservation tools.

- Threats from fragmentation and habitat loss can be mitigated with canopy corridors, cavity retention, and targeted local programs — actions that readers can support through habitat-friendly yard and land-use choices.