Through much of the 20th century, smallholder mixed farms gave way to large, single-crop fields as mechanization, chemical inputs, and market incentives pushed agriculture toward monoculture. Since the 1990s, though, researchers, NGOs and many farmers have quietly reversed that trend, re-embracing diverse planting patterns to repair soils, curb pests, and broaden incomes. Monocultures left behind a string of problems: degraded soil, narrower diets, higher pesticide bills and fragile cash flows tied to one commodity. Polyculture farming — growing multiple crops together — delivers ecological, economic and management benefits that make diversity a practical alternative for many operations. Below are ten concrete advantages, grouped into environmental, economic/social and resilience-focused benefits, with real examples and data you can apply on the farm.

Environmental benefits of polyculture farming

Mixing species on the same land boosts ecosystem services by increasing habitat complexity and resource capture. Below are four clear environmental gains, backed by field examples and published findings.

1. Increased biodiversity and stronger ecosystem services

Planting multiple crops raises on-farm species richness, which in turn supports pollination and natural pest control. Reviews in journals such as Nature and PNAS report consistent gains in beneficial insects and birds on diversified plots versus monocultures.

One FAO synthesis notes large biodiversity losses in simplified agroecosystems and recommends diversity-based designs to restore services (pollinators, predators). Field studies show companion planting and hedgerows can raise beneficial insect counts by tens of percent in many systems.

Practical example: coffee and cacao farms that keep shade trees host more pollinators and insect predators, helping reduce yield losses from pests and improving fruit set.

2. Improved soil health and enhanced nutrient cycling

Diverse root architectures and crop residues improve soil structure and organic matter. Legumes in the mix add biologically fixed nitrogen, while deep-rooted species recycle nutrients from lower layers.

Measurements from multiple trials show mixed rotations and cover-crop mixtures increase soil organic carbon and aggregate stability over time (typical gains reported in trials range from 0.2–0.5 percentage points in SOC across several seasons). That translates into better water holding capacity and nutrient availability.

On a practical level, maize–bean intercrops often reduce commercial nitrogen needs for the cereal crop, lowering fertilizer bills while maintaining yields.

3. Reduced pest and disease pressure without heavy pesticides

Mixing species breaks pest host-finding and supports predators and parasitoids. Habitat strips and companion plants provide nectar, pollen and shelter for natural enemies.

A well-documented example is the ICIPE push–pull system in East Africa (Desmodium intercropped with maize and Napier grass as a trap crop). Farmers report dramatic reductions in stem borer incidence and, in many cases, pesticide use falls sharply while yields rise — often by a factor of two or more compared with untreated monoculture plots.

Other tactics—trap crops, field bean strips that attract parasitoids, and hedgerows—let farmers lower chemical inputs and harness living pest control.

4. Better water retention and less soil erosion

Continuous ground cover from cover-crop mixes and interrows reduces surface runoff and protects soil from raindrop impact. Diverse rooting depths improve infiltration and reduce overland flow.

Watershed and plot studies often show contour intercropping and agroforestry on slopes cut erosion rates substantially; some hillside projects report sediment loss reductions measured in tens of percent after adopting multispecies plantings.

On sloped farms, combining trees, shrubs and annuals on contour bands is a practical way to hold soil in place while producing food and wood.

Economic and social benefits for farmers and communities

Diversified plantings influence livelihoods in three main ways: they spread market risk, improve household diets, and can cut input bills. The examples below show how those channels work on real farms and in community programs.

5. Income diversification and economic resilience

Selling several crops spreads price risk and evens out cash flow across seasons. Secondary or high-value intercrops can supply needed cash when staple prices are low.

Program evaluations and NGO reports commonly find that income from non-staple crops supplies an additional 10–30% of household revenue, which helps households cope with shocks like a failed main crop or market dips.

Practical pathways include intercropping maize with market vegetables, adding fruit trees to field margins, or small-scale processing and cooperative marketing to capture extra value.

6. Improved nutrition and local food security

On-farm diversity increases year-round access to vitamins, minerals and protein sources. Home gardens and integrated livestock systems deliver nutrient-dense foods close to the kitchen.

Evaluations of garden and homestead programs often report measurable rises in dietary diversity and fruit-and-vegetable consumption — many projects show increases in dietary diversity scores on the order of 15–30% for participating households.

Examples include household gardens in South Asia and Africa supplying leafy greens and vegetables through dry seasons, and integrated poultry-plus-vegetable systems that boost local protein access.

7. Reduced input costs and more efficient use of labor

Biological services from diverse plantings lower spending on fertilizer, pesticides and sometimes irrigation. Legumes can supply part of a crop’s nitrogen needs, and natural enemies cut pesticide needs.

Extension reports and trials document cases where legume cover crops replaced a portion of purchased nitrogen and where integrated pest management in diversified plots cut pesticide purchases by substantial margins.

Labor shifts are real: diversity can move work across the season instead of concentrating it, and well-designed planting patterns (e.g., alley cropping, relay intercropping) reduce peak labor demands rather than increase them.

Resilience and farm-management benefits

Resilience is the ability to maintain production and livelihoods under shocks. These next three points show how diversity improves stability, builds productive interactions, and links to policy and market incentives.

8. Greater yield stability and climate resilience

Cropping diversity buffers farms against droughts, late rains and pest outbreaks by spreading risk across species and planting times. That makes harvests more predictable year to year.

Meta-analyses and long-term trials find that multispecies systems often reduce yield variability and in many cases maintain or slightly increase mean yields; reported improvements in stability commonly fall in the range of 10–20% in synthesis studies.

Farmer tactics include staggering planting dates, mixing drought-tolerant varieties with shallower-rooted crops, or adding perennials whose deep roots keep soil moisture available during short dry spells.

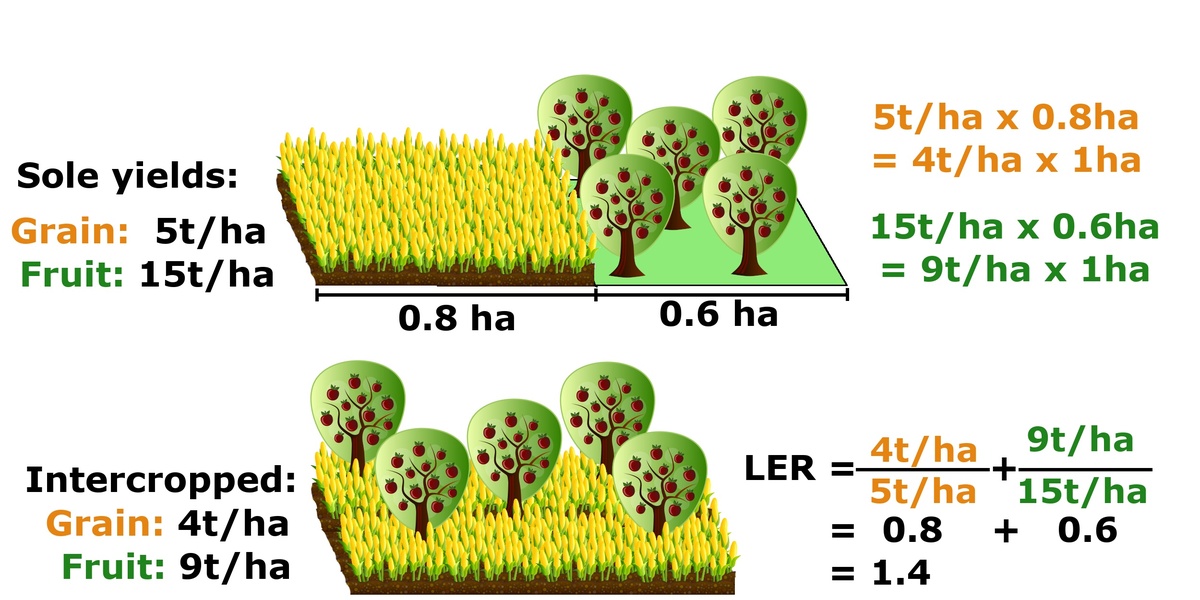

9. Complementary interactions that boost long-term productivity

Certain crop pairs or multispecies mixtures use resources more fully than single crops. One crop’s shade, root depth or nitrogen fixation can benefit its neighbor, increasing total output per hectare.

Experimental plots and long-term agroforestry trials show land productivity gains when cereals are paired with legumes or when trees are combined with annuals. These are system-level benefits that often appear over several seasons rather than in a single year.

Examples: cereal–legume intercrops that transfer nitrogen and improve yields, and tree–crop interactions in agroforestry where mulch and shade-plus-root effects build productivity over time.

10. Policy, market, and scaling opportunities for sustainable systems

Diverse farming systems fit well with payments for ecosystem services, agroforestry carbon projects, and growing consumer interest in sustainably produced foods. Those channels create income streams that reward stewardship.

Organizations such as FAO and national extension services are increasingly promoting agroecology pilots, and some PES pilots and carbon programs now include agroforestry — offering concrete payment pathways for farmers who adopt multispecies systems.

Scaling routes include farmer training, cooperative marketing for mixed products, and simple certification or labeling that helps consumers identify diverse, sustainable produce.

Summary

Polyculture farming brings tangible gains across ecosystems, household livelihoods and farm resilience. The strongest takeaways are practical rather than theoretical.

- Environmental wins: more pollinators and predators, better soil organic matter, lower erosion and reduced pesticide reliance.

- Livelihood benefits: diversified income streams, improved local diets, and lower fertilizer and pesticide bills in many systems.

- Resilience and productivity: more stable harvests through complementary crop interactions and options to access PES or carbon programs.

- Actionable next steps: try a small intercropped test plot this season; contact local extension or FAO resources for design guidance; explore cooperatives or value-added options for diverse products.