When explorers returned from the New World and Siberia in the 18th and 19th centuries, naturalists wrote with a mix of awe and alarm: beavers had reshaped entire valleys into wetlands, rat plagues aboard sailing ships devastated crews and cargo, and lab mice were already revealing surprising patterns in heredity and behavior. Those early accounts set the stage for a long-running human fascination with small mammals that can engineer landscapes, carry disease, be useful in research, or simply chew through a pantry.

Rodents matter because they sit at the intersection of ecology, public health, and everyday life—as ecosystem engineers, disease reservoirs, model organisms, pets, and pests. The following ten characteristics explain how a common set of anatomical and physiological traits produces diverse behaviors and outsized ecological roles. Below are ten numbered characteristics grouped into three categories—Anatomy & Physiology; Behavior & Sociality; and Ecology & Human Interactions—that link teeth and jaws to reproduction, social systems, and our own responses to them. These characteristics of rodents help explain why we study, manage, and sometimes fight them.

Anatomy & Physiology

Many of the traits that make rodents successful are rooted in anatomy and basic physiology. Structural features—particularly teeth, jaw muscles, and skull shapes—define what rodents can eat and how they interact with their environment.

Physiology ties those structures to life history: high metabolic rates, rapid growth, and prolific reproduction produce fast population responses. Those details matter whether you’re caring for a pet rabbit or hamster, managing wild populations, or designing experiments with mice or rats.

1. Continuously growing incisors that specialize for gnawing

Nearly every rodent has a pair of large, chisel-shaped incisors in the upper and lower jaws that grow throughout life. Those teeth are open-rooted—meaning they don’t stop growing—and enamel is laid down mainly on the front surface.

Because enamel is harder on the front than the back, normal wear produces a self-sharpening edge as the softer dentine behind wears faster. That arrangement turns routine chewing into a mechanical sharpening process, which is why many rodents must gnaw constantly to prevent overgrowth.

The practical consequences are immediate: beavers use powerful incisors to fell trees and strip bark; Norway rats will gnaw through wood, plastic, and even soft metals in buildings; and pet owners or veterinarians must check captive rabbits and guinea pigs for dental overgrowth, sometimes trimming or filing teeth to prevent pain and malocclusion.

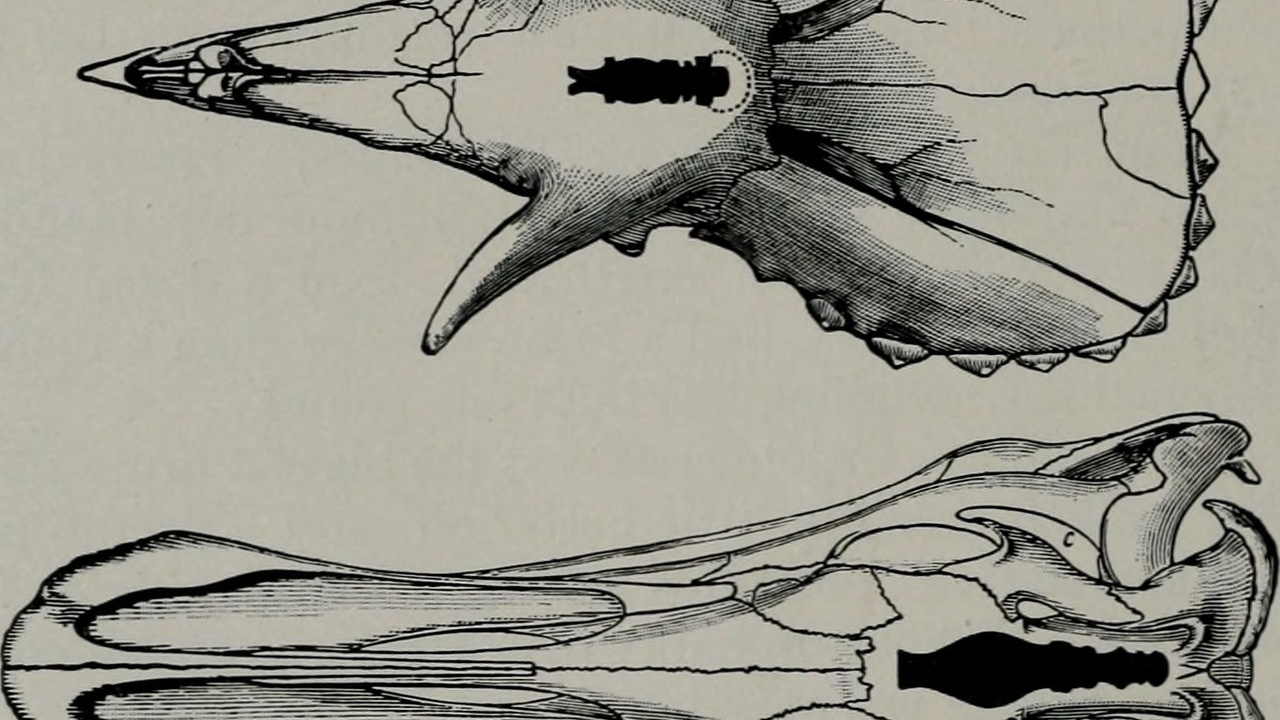

2. Specialized jaw musculature and skull adaptations for powerful gnawing

Rodent skulls and muscles reflect their gnawing lifestyle. The masseter group (the main chewing muscles) is enlarged and repositioned in many species, with a pronounced zygomatic arch and modified jaw hinge that increase bite leverage.

Skull plans vary by feeding niche: sciuromorphs (squirrel-like) have a forward masseter attachment that favors explosive bites for seeds, hystricomorphs (guinea-pig–like) display different leverage for grinding vegetation, and castorids (beavers) show massive, wood-crunching adaptations. For their size, many rodents generate high bite forces—enabling them to process hard seeds, strip bark, or gnaw through building materials.

That biomechanical diversity lets rodents exploit many diets and habitats: beavers can fell trees and alter hydrology, while urban rats chew through electrical wiring and packaging—an important consideration for pest control and structural safety.

3. Small body size with high metabolic rates and fast life histories

Many rodents are small-bodied animals with relatively high basal metabolic rates, which drives frequent feeding and rapid energy turnover. That metabolic profile links to other life-history traits: fast growth, early sexual maturity, and short lifespans.

Take the house mouse: wild individuals commonly live 1–3 years, while lab mice often reach 2–3 years under managed care. Small mammals need frequent access to calories, making them active foragers and sensitive to temperature and food shortages. Those dynamics produce quick population responses to favorable conditions and rapid evolutionary change when selective pressures shift.

There are notable exceptions—capybaras and beavers are large by rodent standards—but the metabolic trade-offs that link size, reproduction, and survival are consistent across the order.

4. Highly fecund reproductive systems: short gestation and large litters

Reproductive rate is a defining feature: many rodents breed quickly, with short gestation periods and substantial litter sizes. A house mouse gestates for roughly 19–21 days and commonly produces litters of several pups.

Norway rats have gestations around 21–23 days and typical litters ranging from five to twelve young, and many species can produce multiple litters per year. Young often reach sexual maturity within weeks to a few months, enabling several generations annually in favorable environments.

Those reproductive dynamics explain why populations can rebound rapidly after control efforts, why rodents are effective laboratory breeders for multigenerational studies, and why pest management requires sustained rather than one-off measures.

Behavior & Sociality

Behavior and social systems determine how rodents interact with each other, their predators, and people. Activity patterns, communication modes, and social structure shape disease transmission, detectability, and ecological impacts.

Because sociality ranges from solitary to highly colonial, management and research approaches must adapt: what works for a lone burrowing species won’t work for a prairie dog town or a commensal rat population living alongside humans.

5. Nocturnal and crepuscular activity patterns

A large portion of rodent species are active at night or during dawn and dusk. Nocturnal and crepuscular schedules reduce exposure to daytime predators, help avoid heat stress, and align foraging with food availability.

House mice and Norway rats are primarily nocturnal, which is why homeowners often notice nocturnal rustling, gnaw marks, or disturbed trash the morning after. Field mice in the genus Peromyscus often show twilight peaks in activity, a behavior researchers account for when planning trapping or observational studies.

Understanding these rhythms improves control strategies (baiting at night, monitoring activity at dawn) and is crucial in lab work where circadian cycles influence physiology and behavior.

6. Complex social structures and communication systems

Social organization in rodents spans solitary breeders to highly organized colonies. Communication uses multiple channels: scent marking, audible calls, ultrasonic vocalizations, and visual or tactile signals.

Research by Con Slobodchikoff on prairie dogs revealed alarm-call complexity that encodes predator type and even descriptive details about humans, a striking example of information-rich signaling. Laboratory mice produce ultrasonic vocalizations—pup calls and adult courtship calls often around 50 kHz—that neuroscientists use to study social behavior and communication.

Social learning occurs in many species, from communal nesting to foraging traditions, and social structure strongly affects disease dynamics: tightly clustered colonies can amplify transmission, while solitary habits may limit spread.

7. Hoarding and caching behaviors that influence plant communities

Many rodents store food for leaner times, using two broad strategies: scatter-hoarding (many small caches spread across a landscape) and larder-hoarding (concentrated stores in a burrow or den). Those behaviors have major ecological consequences.

Scatter-hoarders like some squirrels and chipmunks move and bury hundreds to thousands of seeds each season. Forgotten caches become seedlings, aiding forest regeneration and influencing plant community composition. Ground squirrels and red squirrels, for example, play well-documented roles in tree recruitment patterns.

Hoarding also affects agricultural losses—stored grain can be raided by hamsters or mice—and shapes survival strategies in seasonal climates where cached food buffers winter scarcity.

Ecology & Human Interactions

Rodents occupy a dual role in human affairs: they provide ecosystem services and support scientific progress, yet they also cause crop losses, structural damage, and public-health risks. Managing that balance requires ecological nuance and practical measures.

From wetland creation to lab benches, rodents are central to conservation, agriculture, and biomedical research—and to many of the challenges we try to solve around sanitation, pest control, and zoonotic disease surveillance.

8. Ecosystem engineering and keystone roles

Certain rodents actively reshape habitats. Beavers are the archetypal ecosystem engineers: dam-building floods valley bottoms, creating ponds that expand wetland area, slow water flow, and raise groundwater tables.

Those beaver ponds increase habitat heterogeneity and benefit amphibians, waterfowl, and fish, sometimes adding measurable hectares of wetland across a watershed in an area-specific study. Prairie dog colonies also influence grassland structure through grazing, burrowing, and soil turnover, increasing plant diversity and creating microsites for other species.

When these engineers conflict with human land use—flooded fields, damaged levees, or altered grazing lands—management must weigh ecological benefits against economic costs and seek solutions that retain biodiversity while protecting infrastructure.

9. Disease reservoirs and public-health significance

Rodents host pathogens with real human impacts. Historically, black rats are associated with the spread of bubonic plague (Yersinia pestis) in pandemics such as the 14th-century outbreaks in Europe.

In modern times, hantaviruses drew attention after the 1993 Four Corners outbreak of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome in the U.S., linked to deer mouse reservoirs. Lassa fever remains a pressing concern in West Africa, where Mastomys natalensis serves as a reservoir for the Lassa virus.

Transmission pathways include fleas (for plague), direct contact with infected animals, and inhalation of aerosolized droppings or urine (hantaviruses). Public-health responses rely on sanitation, rodent monitoring, flea control, and surveillance systems coordinated by agencies such as national CDCs and the WHO.

10. Economic and scientific importance: pests, pets, and model organisms

Rodents produce clear economic costs—crop damage, stored-grain losses, and structural repairs run into billions of dollars globally each year—while also supporting major sectors of science and the pet trade.

The house mouse and the lab rat are central tools in genetics, neuroscience, immunology, and drug development. Standard strains like C57BL/6 mice and Wistar rats provide reproducibility across labs, and millions of rodents are used annually in biomedical research worldwide (institutional and international statistics document this scale).

At the same time, popular pet rodents—guinea pigs and Syrian hamsters among them—support a sizeable pet-industry niche and educational uses. Managing pest populations, supporting ethical research practices, and promoting humane pet care all intersect in policy and economics.

Summary

Anatomy, behavior, and human interactions are tightly linked in rodents: ever-growing incisors and specialized jaws lead to gnawing and ecosystem effects, while high metabolism and rapid reproduction underpin their ecological success and pest potential.

- Teeth and skull design drive many rodent impacts—from beavers felling trees to rats chewing infrastructure—and dental health is central in captive care.

- Fast life histories (high metabolism, short gestation, big litters) explain why populations rebound quickly and why rodents are valuable for multigenerational research.

- Behavior and social systems—nocturnality, complex vocal and scent communication, and hoarding—shape ecology, conservation outcomes, and disease dynamics.

- Some species (beavers, prairie dogs) are ecosystem engineers that boost biodiversity, while others are reservoirs for zoonoses; both roles demand tailored management and public-health strategies.

- Understanding the core characteristics of rodents helps guide humane control, conservation timing, and responsible use in science—supporting coexistence and targeted action going forward.