Early 20th-century naturalists crossing the Libyan Sahara recorded species now rare or locally extirpated — a surprising record of biodiversity hidden in one of the world’s driest countries.

Libya covers about 1.76 million km², and roughly 90% of that is Saharan desert, so the animals that survive here show striking adaptations to extreme heat and scarce water. The fauna of Libya includes specialists that act as seed dispersers, grazers, predators and cultural keystone species; they’re indicators of ecosystem health and matter to people for food, transport and tradition.

Below are 10 representative species — mammals, reptiles, birds and invertebrates — with what makes each unique, their conservation status, and how people interact with them. Onward to desert mammals.

Mammals of the Libyan Desert

Mammals in Libya’s sands play outsized roles: they disperse seeds, shape vegetation through grazing, and form predator–prey networks that keep rodent populations and plant communities in balance. People rely on some species directly — not least the domesticated camel — while others are hunted or persecuted. Major threats include overhunting, habitat fragmentation from roads and development, and prolonged droughts.

For conservation status and up-to-date counts, check the IUCN Red List and regional NGO reports such as local wildlife surveys by North African conservation groups. Now for four emblematic mammals.

1. Fennec fox (Vulpes zerda)

The fennec fox is perhaps the best-known small desert carnivore of North Africa and is common across Saharan habitats, including Libya’s dunes and semi-stabilized sands. Adults typically weigh about 1–1.5 kg and are unmistakable for their oversized ears, which help dissipate heat and sharpen nocturnal hearing.

Fennecs are largely nocturnal, digging shallow dens and using a diet of insects, small rodents and plants to stay hydrated. The IUCN Red List provides range and status summaries (Vulpes zerda). They feature in local folklore and serve as a low-key eco-tourism draw, but threats include the pet trade and disturbance of denning sites.

2. Dromedary camel (Camelus dromedarius)

The dromedary is the domesticated large mammal most associated with Libyan desert life. Physically adapted to long travel, camels store fat in a single hump, conserve water through concentrated urine and dry feces, and move easily on sand with broad, splayed feet.

Domesticated dromedaries number in the millions across North Africa and the Middle East and remain central to pastoralist livelihoods: transport, milk, meat and cultural identity. Camels enabled historic trans‑Saharan trade and still support nomadic and semi‑nomadic communities in Libya, where local breeds and herding practices persist despite sedentarization and market pressures.

3. Addax (Addax nasomaculatus)

The addax is a pale-coated, broad‑hoofed antelope once widespread across the central Sahara and historically present in parts of Libya. Its light color reflects sunlight, and wide hooves let it walk on soft sand while moving between sparse grazing patches.

IUCN lists the addax as Critically Endangered (Addax nasomaculatus) after steep declines in the late 20th century from hunting and disturbance. Recent decades have seen captive‑breeding and reintroduction efforts in parts of North Africa (notably programs managed by conservation NGOs and range‑state partners in the 2010s). Restoring addax populations would help recover the ecological role of large grazers, but success requires security, long-term monitoring and community engagement.

4. Barbary sheep (Ammotragus lervia)

Barbary sheep are hardy caprids adapted to rocky highlands, plateaus and escarpments; historical records note them in Libya’s upland desert areas. They’re sure‑footed climbers that use cliffs and rocky outcrops to escape predators and forage seasonally on sparse vegetation.

The IUCN lists regional declines in North Africa due to hunting and habitat loss (Ammotragus lervia). Where populations remain, Barbary sheep support regulated hunting and local ecotourism, but pressures from unregulated take and land‑use change have reduced numbers since mid‑20th‑century surveys. Protected areas and targeted surveys by regional wildlife groups can help identify remnant populations for conservation action.

Reptiles and Amphibians of Libya’s Desert

Reptiles represent a large share of vertebrate biomass in arid zones and show fine‑tuned thermoregulatory and cryptic adaptations. Some are venomous and of medical significance; monitoring them can inform public health and ecosystem trends.

Below are three reptiles often encountered in Saharan Libya; for detailed range maps and seasonality consult regional field guides and toxinology literature when relevant.

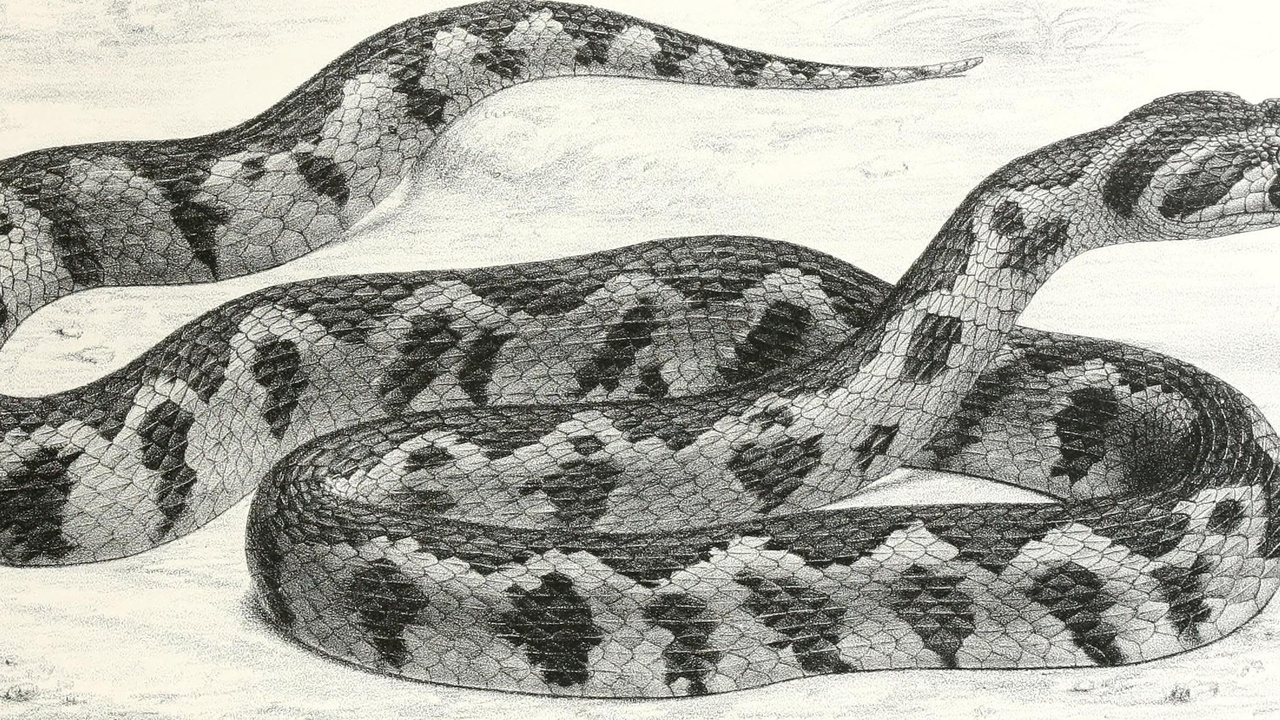

5. Saharan horned viper (Cerastes cerastes)

The Saharan horned viper is a small ambush viper common on sandy plains and dunes. It’s notable for horn‑like supraocular scales, cryptic sand‑colored patterning and sidewinding locomotion that reduces contact with hot sand.

Adults typically reach about 30–60 cm and feed on rodents and lizards. Bites occur sporadically in rural areas; toxinology sources stress rapid access to antivenom in remote clinics. Public education — teaching people to avoid putting hands into burrows or crevices at night — reduces risky encounters and the number of bites recorded in hospital reports.

6. Desert monitor (Varanus griseus)

The desert monitor is a large, powerful lizard of arid plains and rocky wadis. It burrows or occupies abandoned mammal dens, tolerates wide temperature swings and takes an opportunistic diet of eggs, small mammals, birds and invertebrates.

Adults can exceed 1 m in total length depending on locality. Monitors help control pest rodents and insect outbreaks, but they face collection pressure for the pet trade and habitat disturbance near oases. Observations are most common around wadis and springs, where prey is concentrated, and targeted surveys by herpetologists document seasonal activity patterns.

7. Egyptian sand boa (Eryx colubrinus)

The sand boa is a stout, burrowing snake adapted to loose sands. Its body shape and locomotion let it “swim” beneath the surface to ambush rodents and lizards, and many are active at night or around dusk.

Adult sand boas often measure 40–80 cm. They’re frequently found near human settlements where rodent prey is abundant and thus perform a useful pest‑control role. Because they pose little medical risk, education and humane relocation are effective ways to reduce persecution when encounters occur.

Birds and Invertebrates of the Libyan Desert

Birds and invertebrates keep desert systems moving: birds disperse seeds and link migration routes across continents, while invertebrates pollinate, decompose and form the base of many food chains. Some invertebrates, notably scorpions, have direct public‑health relevance.

Here are three species that highlight those roles — consult BirdLife International and toxinology guides for up‑to‑date status and medical advice.

8. Houbara bustard (Chlamydotis undulata)

The houbara bustard is a large, ground‑dwelling bird of arid and semi‑arid lands that breeds in parts of North Africa. It’s culturally significant and subject to intense hunting pressure, especially from falconry and recreational takings across the region.

BirdLife International and IUCN provide status and trend data (BirdLife). Conservation responses include captive‑breeding, transboundary monitoring and partnerships among range states and NGOs; these programs aim to reduce illegal take and restore wild numbers while balancing local livelihoods and international demand.

9. Desert lark (Ammomanes deserti)

The desert lark is a small songbird of stony plains and gravel deserts, cryptically colored for life on the ground. It forages for seeds and insects and breeds in spring and early summer when rains trigger seed flushes and insect abundance.

Desert larks help control insects and move seeds across bare ground. Land‑use changes such as heavy grazing, road building and disturbance of nesting sites influence local abundance; regional surveys and BirdLife notes report relatively stable populations where habitat remains intact.

10. Saharan scorpion (Androctonus spp.)

Members of the Androctonus genus, often called “fat‑tailed” scorpions, are widespread in North Africa and medically important because of potent venom. They’re nocturnal, sheltering under rocks or in burrows by day and hunting insects and small vertebrates at night.

Toxinology literature and regional health reports indicate that envenomation requires prompt medical attention and availability of antivenom in rural clinics. Practical safety tips include shaking out bedding and shoes before use, using a torch at night, and teaching children to avoid handling scorpions. Local knowledge about avoidance and first‑response continues to be valuable in remote communities.

Summary

- Even across 1.76 million km² of mostly desert, Libya supports a surprising range of specialized wildlife that shapes ecosystem function.

- Several species have deep cultural and economic roles — camels for transport and milk, houbara for regional traditions — while others provide practical services like pest control.

- Some taxa are in urgent need of action (for example, the addax is Critically Endangered); effective conservation combines protected areas, captive‑breeding, monitoring and local engagement.

- To learn more or help, consult authoritative sources such as the IUCN Red List and BirdLife International, and support regional conservation groups or responsible ecotourism that benefits local communities.