Bats account for about 20% of all mammal species (more than 1,400 species) and changed how scientists think about mammalian perception when Donald Griffin demonstrated echolocation in 1938. That discovery was as surprising then as the range of bat lifestyles is now: some species swoop like fighter pilots to catch insects, others hover at flowers, and a few even drink blood.

Why care? Bat adaptations underpin critical ecosystem services—pollination, seed dispersal, and insect control—affect public health through disease ecology, and inspire technologies from sonar to agile drones. Bats are the only mammals that sustain powered flight, and a suite of structural, sensory, and behavioral traits—seven of which follow—make that lifestyle possible.

Below the sections are grouped by anatomy, senses, and behavior/physiology so you can see how form, perception, and life history work together to produce remarkable flyers.

Anatomy and Flight Mechanics

Bats evolved true powered flight by radically modifying the forelimb into a wing while keeping a mammal’s overall body plan. Fossils such as Onychonycteris finneyi from the early Eocene (about 52 million years ago) show those early experiments in winged mammals.

Wing shape varies with ecology: high-aspect-ratio wings suit speed and open-air foragers, while short, broad wings favor maneuverability in cluttered forests.

1. Forelimb modification: elongated fingers and a true wing

Bats form a true wing by elongating the metacarpals and phalanges so the fingers support the membrane; the result is a hand-based wing rather than the feathered forelimb of birds (Onychonycteris finneyi documents this early anatomy).

Wingspans vary enormously — small insectivores may span ~20–30 cm, while flying foxes (Pteropus) reach roughly 1.5 m — and aspect ratio correlates with flight style. The Brazilian free-tailed bat (Tadarida brasiliensis) has a high-aspect wing for rapid, straight flight; Myotis species have low-aspect wings for tight turns in cluttered spaces.

Engineers borrow these forms: biomimetic wing designs for small drones use elongated “finger” structures to improve maneuverability and efficiency.

2. The patagium: a multifunctional wing membrane

The patagium comprises several regions (chiropatagium between the fingers, plagiopatagium along the body, etc.) and is much more than skin stretched between bones.

It’s richly vascularized and innervated, with touch receptors such as Merkel cells that help bats sense airflow and manipulate prey midflight. Blood flow through the membrane aids thermoregulation, and small tears can heal, though at energetic cost.

Researchers map wing sensor distributions to improve tactile sensing on robotic membranes, modeling how sensory feedback refines flight control.

3. Lightweight, flexible skeleton and flight muscles

Bats achieve a balance of strength and lightness with thin-walled bones, flexible shoulder joints, and muscling adapted to a wide wingbeat arc rather than the pneumatic skeleton of birds.

Some species have a pronounced keel on the sternum for muscle attachment, and small insectivores can exceed 20 Hz wingbeat frequencies to generate lift and agility.

Those joint and muscle solutions interest MAV designers who aim for agile flight in constrained environments by imitating bat joint flexibility.

Sensory Specializations and Navigation

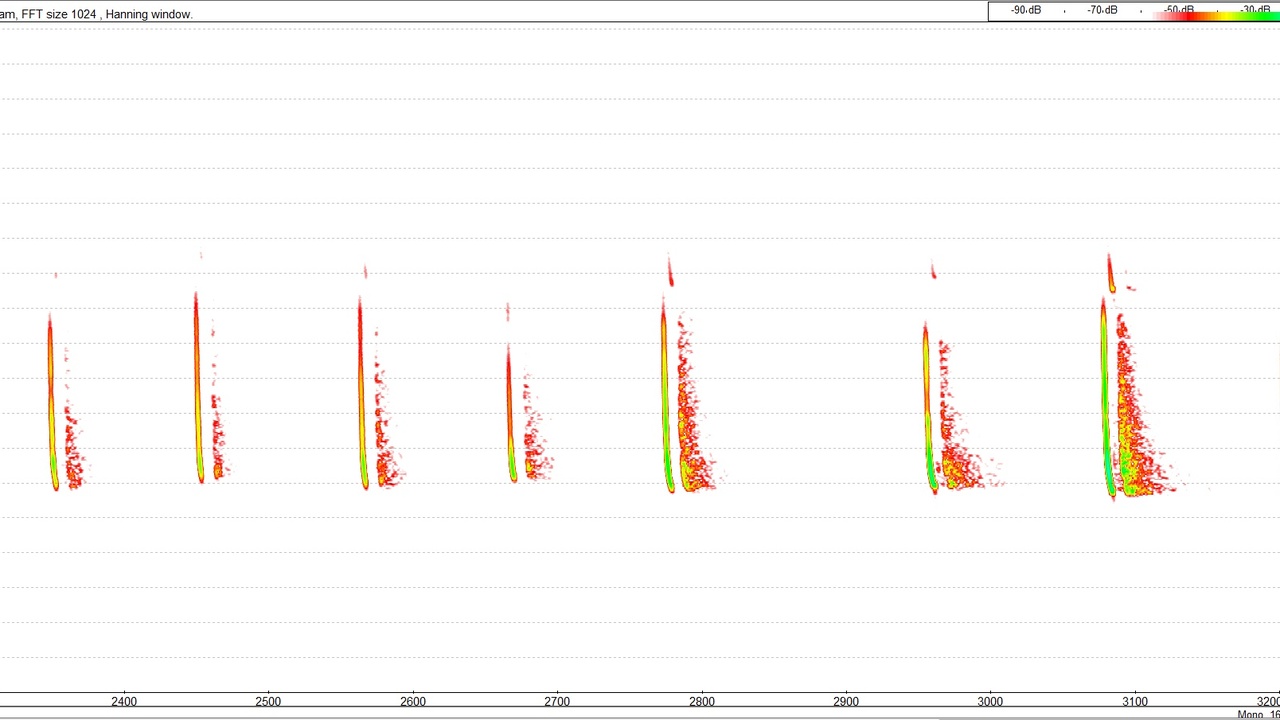

Many bats navigate and hunt with biological sonar, combined with finely tuned hearing and, in some species, additional special senses. Echolocation calls range widely in frequency (roughly 14 kHz to well over 200 kHz) and in structure between constant-frequency and frequency-modulated types.

4. Echolocation: biological sonar

Echolocation is the defining sensory tool for many nocturnal bats: they emit ultrasonic calls and interpret returning echoes to map surroundings and pinpoint prey. Donald Griffin’s 1938 work coined the term and convinced the scientific community this sensory system existed in mammals.

Call strategies vary: horseshoe bats use long constant-frequency elements to detect fluttering insects, while many pipistrelles use short frequency-modulated sweeps for detailed range and texture information. Bats can detect insects only a few millimeters across at close range.

Beyond biology, echolocation inspired advances in sonar hardware and signal-processing algorithms for robotics and search-and-rescue systems using ultrasonic sensing.

5. Auditory and facial specializations: pinnae, cochlea, and noseleaves

Ear and facial anatomy amplify and sculpt sound. Large, movable pinnae and structures like the tragus focus incoming echoes, while an enlarged cochlea supports sensitivity to high frequencies used in calls.

Noseleaves in horseshoe bats act as acoustic baffles to shape emitted calls, whereas many other species direct calls from the mouth and rely more on ear morphology to localize echoes. The vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus) supplements hearing with infrared-sensitive pit organs that locate warm blood vessels.

These form–function matches let species specialize for cluttered forests, open-air pursuit, or close-range prey detection.

Physiology, Behavior, and Life-history

Bats pair demanding flight energetics with life-history strategies that conserve energy, synchronize reproduction with resource peaks, and exploit social living. Behaviors like torpor, maternity colonies, and delayed fertilization are central to population persistence and conservation challenges.

6. Metabolism and torpor: energy management for flight

Powered flight raises basal energy needs: active metabolic rates in bats are often several times those of similar-sized non-flying mammals. To cope, many species use torpor or full hibernation to slash energy use when food is scarce.

Torpor can reduce metabolic rate by up to about 80–90% in some species, lowering body temperature and conserving fat stores. That same physiological strategy makes hibernating bats vulnerable to disturbances and to pathogens such as the fungus behind white-nose syndrome (first widely noticed around 2006), which has caused widespread mortalities.

Medical researchers study torpor and metabolic suppression for potential applications in critical care and long-duration spaceflight.

7. Social roosting, reproduction, and life-history tricks

Many bats form large maternity colonies that provide communal warmth and calf care; Bracken Cave, Texas, hosts roughly 20 million Mexican free-tailed bats during the breeding season, a striking example of concentrated life-history strategy.

Temperate species commonly use delayed fertilization or sperm storage so pups are born when insect abundance peaks (often late spring to early summer), optimizing offspring survival. While large colonies magnify disease and habitat risks, they also make population monitoring and public outreach more feasible.

Social species deliver important ecosystem services—pollination of agave and other plants, and suppression of agricultural pests—so conserving roosts has both ecological and economic value.

Summary

These seven adaptations—wing anatomy, the patagium, lightweight skeleton and muscles, echolocation, ear and facial specializations, torpor, and social life-history strategies—combine to make bats unique among mammals and broadly influential beyond ecology.

- Structural innovations (elongated fingers, flexible skeleton, specialized patagium) enable efficient, maneuverable powered flight.

- Echolocation and ear/nose morphology let many species hunt tiny prey in darkness and inspired sonar and ultrasonic sensing technologies.

- Physiological strategies such as torpor and reproductive timing balance the energetic demands of flight; these traits have medical and conservation relevance (white-nose syndrome impacts highlighted since ~2006).

- Large social colonies amplify ecosystem services (pollination, pest control) but concentrate risks—protecting roosts yields both biodiversity and human benefits.

If you want to help, support bat-friendly habitats, avoid disturbing known roosts, and follow research into biomimetic sensors and conservation efforts that translate these remarkable adaptations into real-world benefits.