Top 10 Beetles

Charles Darwin kept a box of beetles on his table while writing in the 1830s; he later confessed that collecting them was one of his greatest pleasures. That early fascination hints at why these insects captured scientists’ imaginations and fueled some of the first natural-history observations used in evolutionary thought.

Beyond nostalgia, they matter in concrete ways: roughly 400,000 described species exist, and they account for about 40% of named insect species worldwide (see Natural History Museum). From pollinators and decomposers to agricultural pests, coleopterans influence ecosystems and economies at large scales.

Below are ten remarkable examples organized into three groups — iconic and cultural, ecological and economic powerhouses, and striking adaptations that inspire technology — chosen to show why these animals matter for conservation, farming and design. Which one will surprise you most?

Iconic and Culturally Significant Beetles

Some species carry stories as well as natural roles. Historic collectors like Darwin helped establish entomology as a scientific pursuit, and charismatic specimens — whether ancient amulets or giant mounted displays — have long driven public interest. That attention matters: cultural prominence often translates into conservation action, museum exhibits and citizen-science projects that protect habitat.

Ancient symbolism, spectacular size and dramatic morphology all help certain species become flagships for broader ecosystem protection. Museums (for example, the British Museum and the Egyptian Museum) use famous specimens in exhibits that spark curiosity about biodiversity. Local volunteer monitoring programs and school outreach often center on visually striking species because people connect to them more readily than to cryptic invertebrates.

That popular interest has practical conservation implications: when a species becomes a recognizable icon, it can mobilize resources for habitat restoration — think deadwood retention for forest-dwelling species or protection of grazing areas that support dung processors. In short, cultural weight amplifies ecological value.

1. Sacred Scarab (Scarabaeus sacer) — Ancient symbol and ecosystem recycler

The sacred scarab was a central religious symbol in ancient Egypt, appearing on funerary amulets and hieroglyphs from the New Kingdom onward (c. 1550–1070 BCE) and found in tombs now curated in institutions such as the British Museum.

Its cultural reverence grew from an ecological reality: Scarabaeus sacer and relatives roll and bury dung, a process that recycles nutrients and supports soil fertility. That practical service likely reinforced symbolic associations with rebirth and renewal.

Scarab amulets recovered from burial contexts and displayed in major museums keep the connection between natural history and human culture visible today; the species itself is not typically a conservation concern, but its prominence highlights how ecological roles gain cultural meaning.

2. Stag Beetle (Lucanus spp.) — Mandibles, mating displays, and conservation attention

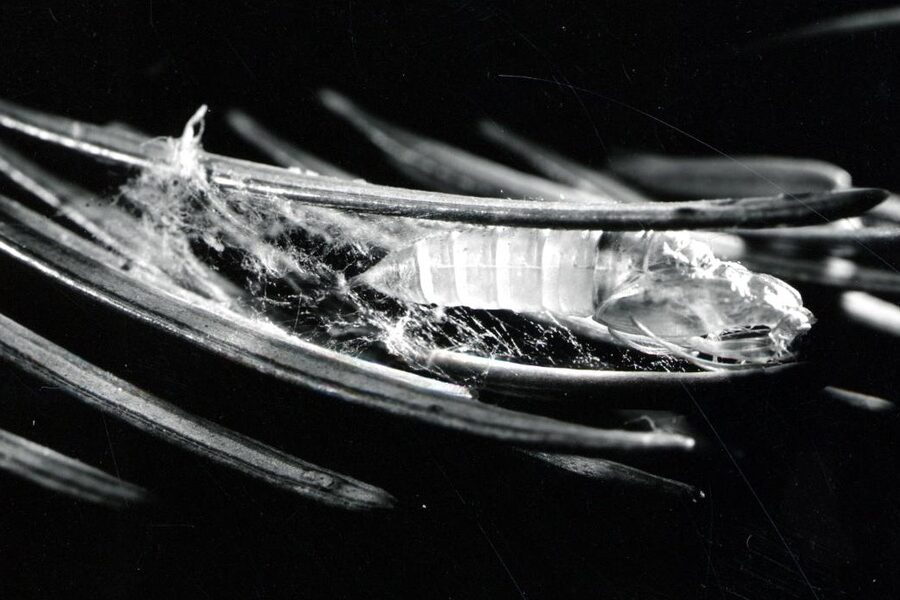

Male stag specimens sport oversized mandibles used in ritualized contests for mates and territory; the dramatic display makes them instantly recognizable and photogenic in public outreach.

They depend on deadwood habitats for larval development, so protecting stag populations usually means protecting veteran trees and fallen logs. That link makes them effective flagship species for forest and urban-woodland conservation programs.

Citizen-science initiatives (for example, the UK stag beetle sightings scheme run by volunteers and conservation groups) help track populations and inform local deadwood restoration projects. In parts of Europe and Asia, several Lucanus taxa are legally protected or prioritized in biodiversity planning.

3. Goliath Beetle (Goliathus spp.) — Size, spectacle, and museum draws

Goliathus species rank among the largest insects by mass, with mature individuals reaching up to about 100 grams. Their sheer scale makes them a museum favorite and an excellent educational ambassador for insect life histories.

Natural-history collections use goliath specimens in exhibits to demonstrate growth, metamorphosis and body-size limits in arthropods, while captive-breeding programs (often run by zoos and specialist breeders) provide living examples for classrooms and outreach.

Because they capture attention, Goliathus and similar large taxa help institutions teach about taxonomy, conservation and the diversity of ecological roles insects fulfill.

Ecological and Economic Powerhouses

Members of this group exert outsized influence on farming and ecosystem function. Some provide services such as pollination, decomposition and biological control; others cause historic and ongoing agricultural damage. Recognizing both sides helps shape management that protects ecosystem services while limiting pest impacts.

Historic examples reveal the scale of those effects: the boll weevil invaded the southern United States around 1892 and reshaped cotton economies across the early 20th century. Modern policy and research (USDA, FAO, and university extension programs) continue to track and manage high-impact species.

For claims about economic losses or service values, consult authoritative sources such as the USDA, the FAO and peer-reviewed literature; those bodies provide estimates for control costs, yield losses and service valuation used by policymakers and farmers.

4. Ladybird Beetle (Coccinellidae) — Natural pest control champs

Ladybird predators are among the most familiar beneficial insects because many species consume aphids, scale insects and other soft-bodied pests used by growers to reduce pesticide reliance. Extension services frequently cite their role in integrated pest management.

Over a lifetime, an individual predator can eat anywhere from several hundred to thousands of aphids, depending on species and conditions, which translates into measurable reductions in pest populations in gardens and greenhouses (see university extension publications).

Harmonia axyridis, introduced in many regions as a biocontrol, illustrates nuanced outcomes: it can suppress pests effectively but sometimes becomes invasive and impacts native fauna. Commercial rearing and greenhouse releases remain common, but practitioners balance benefits against ecological risk.

5. Dung Beetle (Scarabaeinae) — Ecosystem recyclers and disease reducers

Dung processors bury and fragment feces, accelerating nutrient return to soil, improving soil structure and reducing breeding sites for pest flies and parasites near livestock. Their activity can raise pasture quality and decrease disease risk for grazing animals.

Field studies report that assemblages of these insects can bury multiple kilograms of dung per hectare per year, depending on species composition and livestock density; agricultural research programs have deliberately introduced dung processors to improve pasture hygiene and reduce fly pressure.

Practical programs combining research and extension have documented benefits to pasture productivity and animal health; agencies involved in such projects include national agricultural research institutes and university extension services.

6. Japanese Beetle (Popillia japonica) — A costly invasive pest

Popillia japonica is a notorious invader in North America and parts of Europe, defoliating ornamentals, turf and certain crops. Damage can be severe in outbreaks, prompting costly control measures by homeowners, landscapers and farmers.

Management mixes trapping, cultural controls, biological agents and resistant varieties; extension services (for example, state university pest guides) provide region-specific tactics. Economic impacts include both yield loss and the expense of ongoing control programs, which extension and USDA reports routinely quantify.

The broader lesson: global trade and movement of goods continue to spread pests, so prevention, monitoring and rapid response remain high priorities for agricultural biosecurity.

7. Weevils (Curculionidae) — Agricultural history and major crop pests

Weevils include some of agriculture’s most destructive species; the boll weevil (Anthonomus grandis) famously arrived in the United States around 1892 and forced major shifts in southern cotton agriculture through the early 1900s.

Modern control relies on integrated approaches — pheromone traps, monitoring, resistant cultivars and coordinated eradication campaigns — and national programs have demonstrated that targeted investment in detection and removal can be effective and economically justified (see USDA resources).

Preventing spread and rapidly responding to incursions remain central because a single invasive weevil species can transform cropping systems and livelihoods across regions.

Striking Adaptations and Technological Inspiration

Many taxa possess extreme traits — chemical defenses, structural color, powerful flight and remarkable speed — and engineers increasingly study those mechanisms to solve practical design problems. Research published in journals such as the Journal of Experimental Biology and Nature Materials documents how natural solutions translate to prototypes in robotics, coatings and microfluidics.

These examples show how basic natural-history research becomes applied innovation: a defensive spray teaches controlled ejection, intricate cuticle layers inform pigment-free coloration, and agile locomotion inspires small fast robots. Designers borrow principles rather than copy forms, yielding durable and often low-energy solutions.

Below are three standout taxa that have moved from curiosity to concrete engineering inspiration.

8. Bombardier Beetle (Brachininae) — Rapid chemistry and microfluidic inspiration

Bombardier species mix hydrogen peroxide and hydroquinones in a reaction chamber to produce a hot, pulsed defensive spray; valves and a catalytic reaction chamber network let the animal release repeated bursts rather than a single discharge.

Engineers study that pulsed-release mechanism to design microfluidic valves and rapid-release systems where precise, repeatable ejection of small volumes is required. Work cited in biomechanics and chemical-ecology literature points to designs that mimic the beetle’s timing and chamber geometry for controlled micro-ejections.

Applications include lab-on-a-chip devices and micro-actuators where biological timing and containment strategies inform safer, energy-efficient mechanical alternatives (see articles in JEB and related engineering journals).

9. Jewel Beetle (Buprestidae) — Structural color and materials science

Many jewel specimens display iridescence produced by microscopic multilayer cuticle structures rather than pigments. Those nanostructures produce brilliant, angle-dependent colors that resist fading because the effect comes from physical geometry.

Materials scientists replicate these multilayer arrangements to create durable, pigment-free coloration for anti-counterfeit markers, low-energy coatings and colorfast finishes. Research published in materials journals has produced prototypes that mimic elytral microstructure for sustainable coloration approaches.

Such biomimetic coatings offer promising routes to long-lived color without toxic dyes, and they illustrate how studying surface architecture in nature can yield practical manufacturing techniques (see Nature Materials studies).

10. Tiger Beetle (Cicindelinae) — Speed, vision, and robotics models

Tiger taxa rank among the fastest running insects relative to body length and pair that speed with excellent vision and rapid predatory responses; biomechanics studies quantify running speeds in body lengths per second to benchmark performance.

Robotics researchers analyze their locomotion and sensorimotor integration to design small robots that require fast acceleration, agile turns and low-latency navigation. Published experiments measuring stride mechanics and visual processing inform control algorithms for rapid autonomous platforms.

These beetle-inspired models help engineers build nimble, lightweight robots for search-and-rescue, environmental monitoring and exploration where speed and sensing matter at small scales.

Summary

- About 400,000 described species (roughly 40% of named insects) show how diverse and abundant these animals are, and that diversity underpins major ecological and economic effects.

- Certain taxa function as ecosystem engineers and biological-control agents, while others have reshaped agriculture historically (for example, the boll weevil after ~1892); both benefits and risks deserve continued monitoring via agencies such as the USDA and university extension services.

- Unique adaptations — the bombardier’s pulsed chemistry, jewel-beetle structural color and tiger-beetle locomotion — have already inspired microfluidics, materials and robotics research, showing that natural history fuels practical innovation (see Journal of Experimental Biology and materials-science literature).

- Simple conservation actions help: planting native species, retaining deadwood in yards, and participating in citizen-science monitoring all support these taxa and the services they provide.