Mid-19th-century naturalists watching the rise of industrial soot noticed a dramatic shift in moth coloration — the peppered moth story became the first widely told example of camouflage’s role in evolution (industrial melanism, mid-1800s).

Camouflage isn’t just about blending in — it’s a suite of biological tricks shaped by evolution that affects survival, hunting, communication, and even modern technology. You should care because concealment strategies determine who eats whom, shape animal behavior in surprising ways, and inspire materials and monitoring tools people use today.

This piece lays out seven facts about animal camouflage, each grounded in research or classic natural-history examples, and explains why those facts matter for ecology and conservation.

How Camouflage Works: Mechanisms

Camouflage operates through three broad mechanisms: background matching (crypsis), disruptive coloration that breaks an outline, and active physiological changes in color or texture. The next three facts unpack each mechanism with concrete examples—from the peppered moth and classic 1950s experiments to zebra striping effects and cephalopod rapid-change skin informed by genomic work in 2015.

1. Crypsis: Background matching drives survival

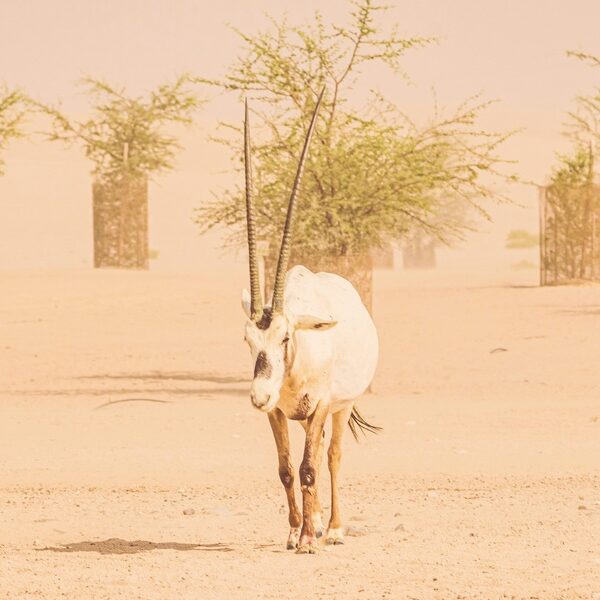

Crypsis, or background matching, is the most common form of concealment: animals evolve coloration that makes them look like their surroundings so predators overlook them. The peppered moth (Biston betularia) is the canonical example—mid-19th-century observers first noted dark, soot-associated forms, and Bernard Kettlewell’s mark–recapture experiments in 1953–1955 linked bird predation to shifts in morph frequency.

The mechanism is simple in concept: by matching background color and pattern, an animal reduces contrast and contours that a visual predator uses to detect it. Cryptic reef fish that closely resemble coral or algal patches provide everyday examples; detection rates drop when prey blend into the visual noise of their habitat.

2. Disruptive coloration and outline breaking

Disruptive coloration works by breaking up an animal’s outline so that a predator cannot assemble a recognizable shape from visual cues. Bands, spots, and false edges confuse edge-detection in predator vision, making bodies appear fragmented.

Plains zebras (Equus quagga) offer a striking, measurable example: field studies indicate striped coats reduce biting-fly landings by roughly 50% compared with solid coats. That reduction lowers disease transmission and energy loss, showing ecological payoffs that go beyond mere concealment. Moths and other insects use false-edge markings for the same outline-breaking effect.

3. Active camouflage: color and texture on demand

Active, physiological camouflage lets animals change appearance in seconds to minutes through neural or hormonal control. Cephalopods—cuttlefish and octopus—are the poster children: skin arrays of chromatophores, iridophores, and papillae modify color, reflectance, and texture to match or masquerade.

Genomic work, including the sequencing of the California two-spot octopus (Octopus bimaculoides) genome in 2015, has helped researchers probe the molecular basis of skin control and neural patterning. The outcome is striking flexibility: animals can blend into backgrounds, create motion-dazzle patterns, or display signals to conspecifics when needed.

Why Camouflage Matters: Survival Strategies

Camouflage shapes predator–prey dynamics, enables ambush predation, and underpins mimicry systems that reorganize communities. The next two facts show how concealment alters survival outcomes—seasonal camouflage can become a liability under climate change, while mimicry demonstrates how deception operates at the community level.

4. Seasonal camouflage and climate risk

Seasonal molts and plumage changes—like white winter coats—are adaptive when they match seasonal snow and ice, but they can become maladaptive if snow cover declines. Snowshoe hares (Lepus americanus) molt in response to photoperiod to gain a white winter coat, yet earlier snowmelt and reduced snow duration create mismatches between coat color and environment.

Empirical studies show those mismatches raise predation risk substantially; in some populations color mismatch increases mortality by more than 20–30%. Conservationists now monitor molt timing and consider adaptive management, because climate-driven shifts can quickly change the selective landscape for seasonal camouflage.

5. Mimicry and deception: more than hiding

Mimicry uses resemblance for deception rather than concealment. In Batesian mimicry a harmless species mimics a harmful model; in Müllerian mimicry, multiple unpalatable species converge on a shared warning signal to mutual benefit. These systems alter predator learning and community composition.

Butterflies provide classic examples: the monarch (Danaus plexippus) was long held as unpalatable and the viceroy (Limenitis archippus) as a Batesian mimic, though later work revealed nuance—viceroys can be unpalatable too, suggesting a Müllerian component in many populations. Such mimicry rings reduce attacks across entire communities by reinforcing predator avoidance.

Camouflage and People: Technology, Research, and Conservation

These seven facts about animal camouflage also point toward practical uses in design and conservation. Engineers borrow natural strategies to build materials and patterns, while ecologists apply new sensors and algorithms to detect cryptic species that standard surveys miss.

6. Biomimicry: from cephalopods to fabric and pixels

Designers have long looked to animals for concealment solutions. A recent, concrete policy example is the U.S. Army’s 2015 adoption of the Operational Camouflage Pattern (OCP), a move driven by field performance across varied environments rather than a single visual trend.

At the same time, research in the 2010s produced lab prototypes—electrochromic panels, e-ink fabrics, and soft materials inspired by cephalopod skin—that can change color or reflectance on command. Those systems show promise for adaptive clothing, vehicle coatings, and dynamic displays, but most remain prototypes or niche products because of power, durability, and cost limitations.

7. Conservation, monitoring, and the challenge of cryptic species

Camouflage complicates wildlife monitoring: cryptic animals are easy to miss with visual surveys and camera traps tuned to obvious shapes. That reality has pushed conservationists to adopt thermal imaging, multispectral sensors, and machine-vision methods to improve detection.

From the late 2010s onward, machine-learning approaches have been increasingly applied to camera-trap data, yielding notable improvements in detecting camouflaged forest species and reducing false negatives. Better detection leads to more accurate population estimates and more targeted conservation actions for threatened cryptic species.

Summary

- The peppered moth story (mid-19th century; 1950s experiments) remains a clear illustration of background matching and natural selection.

- Camouflage works through three mechanisms—background matching, disruptive patterns, and active change—and each has distinct ecological roles.

- Surprising outcomes include zebra stripes cutting biting-fly landings by about 50% and seasonal molts that can raise predation risk by more than 20–30% when snow cover shifts.

- Studying concealment inspires adaptive materials and better survey tools (from the U.S. Army’s 2015 OCP to 2010s cephalopod-inspired prototypes and late-2010s machine-vision), and improved detection helps conservation science.