8 Facts About Deforestation

Between 2015 and 2020 the world lost roughly 10 million hectares of forest each year, and forests still cover about 31% of the planet’s land area (FAO).

That scale matters because forests are central to climate regulation, species survival, freshwater cycles, and the livelihoods of hundreds of millions of people. Losing tree cover doesn’t just change a map — it changes rainfall patterns, releases stored carbon, and shrinks habitat for wildlife and local economies alike (Global Forest Watch; IPCC).

Deforestation is not a single problem but a collection of interlinked facts — on rates, causes, ecological harm, climate impact, and human consequences — that together explain why protecting and restoring forests matters for people and the planet. Below are eight evidence-backed facts that clarify the scale, drivers, impacts, and responses to forest loss.

Scale and Primary Drivers of Forest Loss

1. Rapid global forest loss: roughly 10 million hectares lost per year (2015–2020)

From 2015 to 2020 the Food and Agriculture Organization estimated an average net loss of about 10 million hectares of forest each year, while global forest cover remained near 31% of land area (FAO 2020).

To put that figure in human terms: 10 million hectares is an area roughly the size of Portugal lost every single year. Satellite-based monitoring also shows regional spikes — for example, the Brazilian Amazon experienced around 10,000 km² of tree cover loss in 2020 alone (Global Forest Watch).

That persistent, large-scale loss matters because it subtracts from the planet’s capacity to store carbon, fragments habitats at continental scales, and undercuts the resource base local communities depend on.

2. Farming and commodity production drive most forest clearance

Agriculture — both commercial and smallholder — accounts for the largest share of tropical deforestation. In many hotspots, commodity-driven clearing explains the bulk of recent losses.

Commercial agriculture includes beef and soy in Brazil, oil palm in Indonesia and Malaysia, and rubber or cocoa in parts of West Africa and Southeast Asia. Smallholder expansion and shifting cultivation also continue to convert forest where population pressure and land scarcity are high. Logging, mining, and road-building often precede or enable agricultural conversion, while illegal activities such as artisanal gold mining have driven localized surges in loss (examples: Brazilian Amazon and parts of Peru).

Supply-chain links mean consumer choices — meat, palm-oil products, and soy-fed animals — are directly connected to where forests are cleared, which is why traceability and corporate commitments matter for change.

Ecological Consequences

3. Deforestation is a major driver of biodiversity loss — forests host most terrestrial species

Forests are home to the majority of terrestrial species; tropical forests in particular contain exceptionally high species richness and endemism (IUCN; IPBES). Removing habitat increases extinction risk by shrinking populations and isolating them in fragments too small to sustain viable populations.

Real-world losses are visible: orangutan populations in Borneo and Sumatra have declined sharply as peat and lowland forest were converted to plantations; jaguars and tapirs face shrinking ranges in parts of the Amazon where ranching and roads expand; amphibian declines in Central America have been tied to forest degradation and disease spread.

Beyond charismatic species, biodiversity loss erodes ecosystem functions — pollination, pest control, seed dispersal — that support agriculture and fisheries, with ripple effects on food security and incomes.

4. Clearing forests weakens soils and alters water cycles, increasing erosion and flood risk

Trees stabilize soils, promote infiltration, and moderate runoff. When forests are removed, landscapes become more prone to erosion, sedimentation of rivers and reservoirs, and flash floods during heavy rains.

Examples are plentiful: deforested slopes in parts of Southeast Asia and the Himalayan foothills have produced damaging landslides and greater downstream sediment loads; melting of vegetative cover in watersheds can reduce groundwater recharge and degrade soil fertility, undermining long-term agricultural productivity.

For communities downstream, the costs show up as lost fish habitat, clogged hydroelectric reservoirs, and more frequent destructive floods — all avoidable with better land management and restored forest cover.

Climate, Carbon, and Fire

5. Forest loss releases carbon and accounts for a substantial share of global emissions

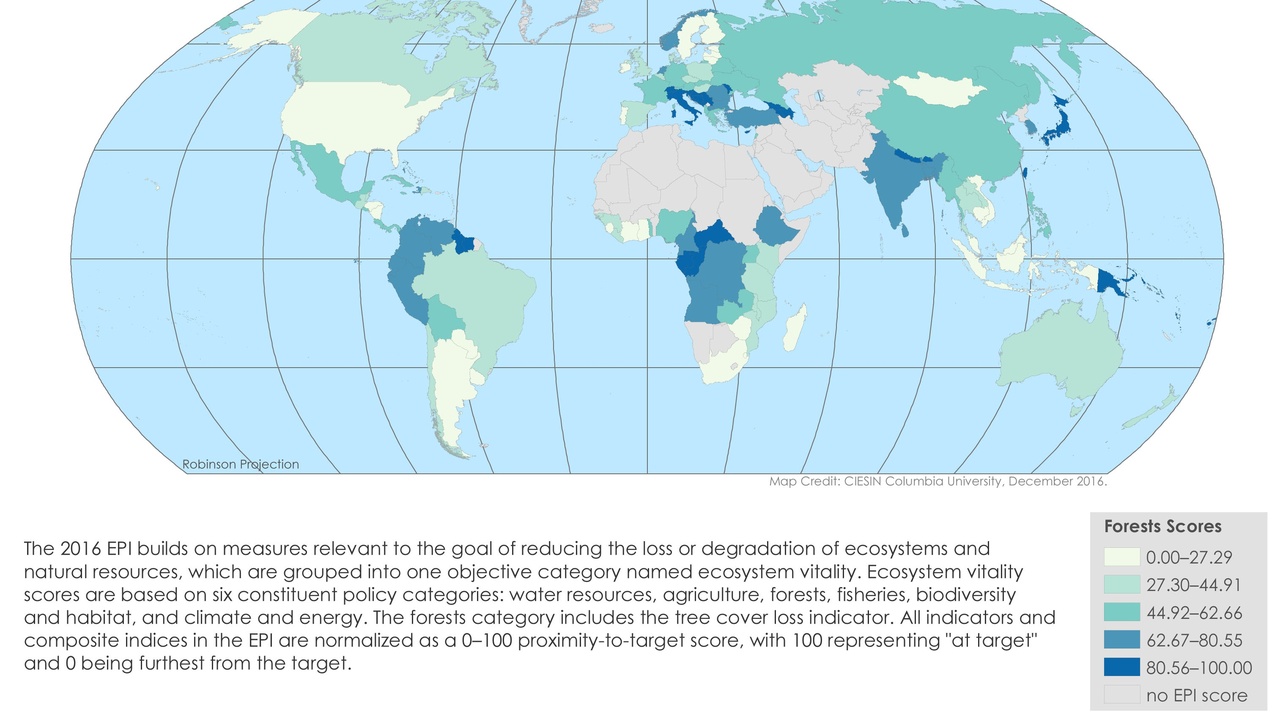

When trees are cut or burned, the carbon stored in their biomass and, in some cases, soils and peat, is released as CO2. Estimates from the IPCC and FAO place emissions from land-use change — much of it deforestation — at roughly 10–12% of global greenhouse gas emissions annually.

That percentage is calculated by combining estimates of biomass loss with measurements of soil and peat carbon changes and adding emissions from fires. For nations like Brazil and Indonesia, land-use change can be among the top national emissions sources, so protecting forests is often a cost-effective climate mitigation strategy (REDD+ frameworks are one policy response built around this logic).

6. Peatland drainage and fires produce outsized emissions and long-lasting damage

Tropical peatlands store enormous amounts of carbon per hectare. When drained for plantations or agriculture and then burned, they emit huge pulses of CO2 and produce transboundary haze that affects health, transport, and economies.

The 2015 Indonesian fires are a stark example: peat and forest combustion released a major pulse of emissions for the year and generated regional air pollution that sickened hundreds of thousands and disrupted aviation. Restoring peatlands is slow and expensive, which makes avoiding drainage a high-impact policy choice.

Because peat systems accumulate carbon over millennia, damage is effectively irreversible on human time scales unless extensive, long-term restoration is undertaken.

People, Policy, and Recovery

7. Deforestation disproportionately affects indigenous peoples and local livelihoods

Millions of people rely on intact forests for food, medicine, cultural practices, and income. When forests are taken for large-scale agriculture or mining, those communities often lose access to essential resources and face displacement.

Evidence shows secure indigenous land tenure frequently correlates with lower deforestation rates in the Amazon and elsewhere — local stewardship matters. Conversely, weak governance and unclear rights can open the door to illegal clearing that undermines rural livelihoods.

Supporting community forestry and recognizing traditional rights are not only justice measures; they are practical conservation strategies that keep forests standing while sustaining people.

8. Policies and restoration can work — from enforcement to reforestation and supply-chain reforms

Targeted policies and investments have produced tangible reductions in clearing where political will, monitoring, and enforcement aligned. Brazil’s significant decline in Amazon deforestation between about 2004 and 2012 combined satellite monitoring, law enforcement, and economic measures to reduce clearing.

Restoration initiatives, payment-for-ecosystem-services programs, and private-sector commitments to eliminate deforestation from supply chains can also help — though corporate pledges need transparent traceability and accountability to be effective.

At the individual and institutional levels, the practical steps are familiar: strengthen land rights for forest stewards, enforce forest laws, finance high-integrity restoration (using native species and attention to local needs), and push for commodity traceability so markets stop rewarding conversion. These combined measures have reversed losses before and can do so again.

Summary

Here are the key takeaways from these eight facts, with concrete implications for action.

- Forest loss is vast and ongoing: roughly 10 million hectares lost per year, driven mainly by agriculture and commodity expansion — a problem with global climate, biodiversity, and local livelihood consequences.

- Deforestation strongly amplifies extinction risk and degrades soils and water systems; peatland drainage and fires are especially damaging and release outsized carbon.

- Protecting forests is a cost-effective climate tool and a social justice issue: secure indigenous tenure and stronger governance reduce clearing.

- Evidence shows recovery is possible: enforcement, transparent supply chains, and well-planned restoration (not tree monocultures) produce measurable wins — and you can play a role through informed purchases, supporting rights-based policies, or joining local restoration efforts.