Every year, roughly 1.5 million wildebeest and hundreds of thousands of other grazers complete the Serengeti’s Great Migration — one of the largest animal movements on Earth. That single statistic helps explain why Tanzania’s wildlife draws so much attention: the Serengeti and its seasonal pulse; Ngorongoro’s crater-bottom oases; Lake Manyara’s bird-rich shores; and vast protected corridors where animals still roam relatively freely. Wildlife here shapes landscapes and livelihoods, funding lodges, guiding services and community projects that together form a major part of the national economy — and for good reason. This piece profiles the 12 most famous animals of tanzania, showing what makes each species iconic, where you can see them, how they influence ecosystems, and which conservation measures are helping or still needed. Below you’ll find the 12 animals grouped into four thematic categories to make their ecological roles and conservation status easy to follow.

The Giants of the Savanna

Large-bodied species — elephants, giraffes and hippos — act as ecosystem engineers. Their sheer size lets them reshape woodlands, open dense thickets, move nutrients and create microhabitats that other species rely on. Elephants knock down trees and open savanna corridors, giraffes browse high foliage that few others reach, and hippos shuttle terrestrial nutrients into rivers and floodplains. That ecological influence also translates into strong tourism value: sightings of big, charismatic animals drive safari bookings and support local economies around Tarangire, the Serengeti and the southern ecosystems. Yet large mammals also bring friction with people — crop-raiding elephants and hippos in riverine villages, or giraffes struck by snare injuries — so conservation must combine protection with community-based mitigation. The Giants category focuses on these ecological roles, the quantifiable services they provide (for example, adult African elephants can weigh several tonnes and reach more than 3 m at the shoulder), and real-world examples of conservation work in Tanzania.

1. African elephant

The African elephant is Tanzania’s largest land mammal and an unmistakable savanna engineer. Adult elephants commonly weigh between about 3,000 and 6,000 kg and males can stand over 3 m tall at the shoulder, allowing them to push over trees and open pathways across the landscape.

Tanzania hosts one of East Africa’s significant elephant populations, concentrated in places like Tarangire National Park, Ruaha and parts of the Serengeti ecosystem; surveys vary by year, but these populations are crucial for regional connectivity. In Tarangire, regular elephant herds shape acacia and baobab distributions, and many safari operators list elephant sightings among their top-selling highlights.

Ecologically, elephants disperse seeds, create water access points by scraping for water in dry seasons and maintain open savanna for grazers. Economically, they underpin lodge bookings and photographic safaris. Threats remain: poaching for ivory, habitat loss and crop raiding that fuels local resentment. On the conservation front, Tanzania supports anti-poaching patrols, community-based elephant monitoring and transboundary collaboration with neighboring countries under CITES frameworks and national enforcement programs.

2. Giraffe (Masai giraffe)

The Masai giraffe is instantly recognizable by its ragged, leaf-shaped patches and towering neck; adults often reach about 4.5–5.5 m in height, with large males weighing up to around 1,200 kg. Their patchwork coat is both identification and camouflage among trees.

As browsers, Masai giraffes prune tree canopies and shape the vertical structure of savannas, benefiting bird species that use the mid- and upper-canopy. They’re also a visitor favorite — a Masai giraffe sighting in the northern Serengeti or Tarangire is often a highlight in lodge photo galleries and marketing.

Conservation efforts include population monitoring across the Serengeti-Mara ecosystem, targeted translocations where local numbers have dipped, and anti-poaching measures. Habitat fragmentation and localized poaching are concerns, but where monitoring is consistent, some local populations have shown stability or modest recovery.

3. Hippopotamus

Hippos are semi-aquatic giants that spend daylight hours in rivers and lakes, then graze at night; adults typically weigh between 1,300 and 1,800 kg. Despite a lumbering appearance, they retain surprising territoriality in water and can be dangerous to people who venture too close.

Hippos shape waterways by creating and maintaining channels, and their dung transports nutrients from land to aquatic systems, supporting fish and invertebrate communities. In Tanzania, hippo pods are a common sight on Rufiji River boat safaris and in parts of the Selous (now Nyerere) ecosystem, drawing wildlife tourists while occasionally causing conflict with riverside communities when access to water or fishing is affected.

Conservation issues include habitat change from upstream water extraction or pollution, and local safety concerns that require designated river corridors and community education. Where boat-based tourism is well managed, hippos contribute substantial income through guided safaris and river cruises.

Apex Predators

Apex predators — lions, leopards and cheetahs — regulate herbivore numbers, remove weak individuals and help maintain ecological balance. They also occupy a potent place in culture and tourism: predator encounters produce some of the most sought-after photographs and stories from Tanzania’s parks. Predators can clash with pastoral livelihoods, leading to retaliatory killings, and their populations are sensitive to human pressures and prey availability. In several parks, lion densities can exceed ten adults per 100 km² in high-quality habitat, underlining how spatial protection matters. This section highlights how top predators function ecologically, where to see them and the conservation strategies used to monitor and mitigate conflict.

4. Lion

The lion is Tanzania’s most emblematic big cat, a cultural symbol and safari staple. Prides vary in size but commonly range from half a dozen to a dozen or more individuals; males are distinguished by manes that can vary with region and age.

As apex predators, lions influence prey behavior and population dynamics, shaping the savanna mosaic. They are a major draw for photographers and lodges, with central Serengeti and the Ngorongoro Conservation Area among the best places to observe pride dynamics and cooperative hunting.

Conservation responses include lion monitoring programs using field observations and GPS collars, community compensation schemes to reduce retaliatory killings, and livelihood projects to reduce dependence on vulnerable livestock grazing areas. Despite these efforts, habitat loss, reduced prey and conflict remain ongoing challenges.

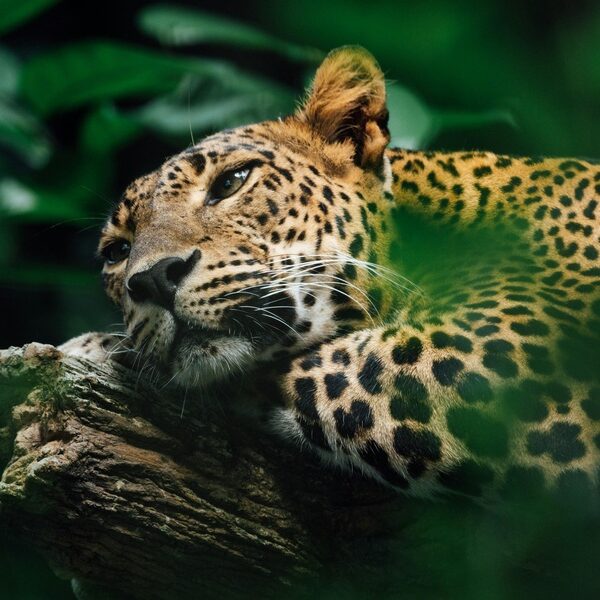

5. Leopard

Leopards are famous for their stealth and tree-climbing habits, where they often stash kills away from scavengers. Adults typically weigh between about 30 and 65 kg, and solitary territories can span tens to hundreds of square kilometers depending on prey density.

Leopards are flexible predators that occupy forests, rocky outcrops and even human-dominated landscapes, preying on a range of small-to-medium mammals and thus helping control those populations. Their ability to haul prey into trees makes for dramatic photographic opportunities — you’ll sometimes see leopards photographed aloft in acacias in the southern highlands and parts of the Serengeti.

Their secretive nature makes population estimates difficult, so camera traps and genetic analyses are widely used for monitoring. Threats include snaring, habitat fragmentation and retaliatory killing; targeted anti-poaching work and improved community reporting systems are key conservation tools.

6. Cheetah

The cheetah is the fastest land animal, capable of short sprints of roughly 100–120 km/h, and it prefers open plains where it can accelerate quickly. Adults are relatively light and built for speed, with narrow bodies and long legs adapted to burst hunting.

Cheetahs help regulate medium-sized ungulate populations and provide spectacular viewing when high-speed hunts succeed. In Tanzania, the open plains of the Serengeti remain the most reliable place to observe cheetah family groups and their hunting technique, though sightings are rarer than for lions or leopards.

Conservation concerns include loss of contiguous habitat, competition and kleptoparasitism from lions and hyenas, and limited genetic diversity in some groups. Programs that monitor cheetah family units and protect important open-country habitats are central to maintaining local populations.

Herds, Grazers, and the Great Migration

The Great Migration is the defining rhythm of Tanzania’s grasslands; roughly 1.5 million blue wildebeest (and hundreds of thousands of zebras and gazelles) move seasonally in search of fresh grazing and water. Seasonal rains drive the timing and routes, and the mass movements shape predator-prey dynamics, grassland regeneration and nutrient cycling across the Serengeti–Mara landscape.

Tourism around the migration is tightly calendared — operators market river-crossing windows at the Mara-Serengeti border and spawning calving seasons on the southern plains — bringing substantial revenue to protected areas and adjacent communities. Grazers like wildebeest and plains zebra create grazing pressure that rejuvenates grasses, while cape buffaloes and other large herbivores maintain wetland edges and support predator diets. This category highlights the migration’s scale and the species that make it a global spectacle.

7. Blue wildebeest

The blue wildebeest is the migration’s flagship — estimates of the migrating population range roughly between 1.2 and 1.5 million animals. They move in vast herds that follow seasonal growth of pasture across the Serengeti-Mara ecosystem.

Wildebeest grazing pressure promotes grass turnover, which benefits short-grass specialists and resets succession after rainy seasons. Their mass crossings of rivers like the Mara create dramatic predator-prey interactions and are a major global wildlife spectacle that attracts photographers and natural-history film crews.

Threats to migration include fences, land conversion and climate variability that alter rainfall patterns. Protecting migratory corridors (such as the Mara-Serengeti border crossings) and coordinating land use with pastoral communities are essential to maintain the migration’s scale and timing.

8. Plains zebra

Plains zebra are conspicuous, striped grazers that often move in mixed herds with wildebeest; their herd sizes can range from small family groups to large aggregations during migration. The striping serves multiple hypothesized functions, from predator confusion to insect deterrence.

Zebras graze differently from wildebeest, often cropping taller grasses and facilitating a mosaic of swards that benefits a diversity of grazers. They are important prey for large predators and are exceptionally photogenic, making them a favorite for safari guests in central Serengeti and surrounding plains.

Reliable zebra congregations are a staple of many game drives, and their presence helps safari operators plan photographic itineraries during migration seasons.

9. Cape buffalo

Cape buffalo are formidable, social grazers often found in wetlands and floodplain edges; herds can range from a handful of individuals to hundreds, and they are known for defensive group behavior that deters predators. They are one of the classic “Big Five” species that many safari guests seek.

Buffalo influence vegetation structure through heavy grazing and create predictable predator opportunities, which in turn sustain lions and hyenas. Their presence near watering holes also concentrates wildlife viewing and supports lodge itineraries that advertise Big Five sightings.

Challenges include disease transmission between buffalo and livestock (e.g., bovine tuberculosis concerns in some areas) and local management of shared water resources. Effective veterinary surveillance, controlled grazing zones and community engagement help reduce conflict and maintain healthy buffalo populations.

Wetland Wonders and Conservation Icons

Tanzania’s wetlands, saline lakes and critically endangered species bring a different kind of value: unique ecological processes, spectacular shorebird gatherings and flagship mammals that attract international attention and funding. Specialized habitats — from the soda waters of Lake Natron to the braided Rufiji River system — host species found nowhere else, and those species often require targeted protection. Conservation icons like the black rhinoceros focus fundraising and policy effort, while wetland services support fisheries, grazing and local livelihoods. This section considers freshwater and saline specialists and the conservation actions protecting them.

10. Nile crocodile

The Nile crocodile is a top freshwater predator in Tanzania’s rivers and lakes, commonly reaching lengths of 3–5 m and employing ambush predation from submerged waits. They are effective scavengers and hunters, influencing fish populations and riverbank ecology.

Visitors encounter Nile crocodiles on boat safaris in the Rufiji and in sections of the former Selous (now Nyerere) Game Reserve, where careful boat routes and ranger guidance keep wildlife viewing safe. Crocodiles also create hot spots of scavenging activity that benefit other species.

Human-crocodile conflict arises where people fish or bathe at river edges; management responses include designated safe access points, signage, and community awareness programs coordinated by reserve managers to reduce risk while preserving crocodile populations.

11. Lesser flamingo

The lesser flamingo breeds in spectacular gatherings on saline lakes; Lake Natron in northern Tanzania is one of East Africa’s most important breeding sites (hosting tens to hundreds of thousands of birds in strong years). Their pink flocks form dense, photogenic colonies on alkaline flats that few other species can use.

Flamingos depend on specialized algae and cyanobacteria, so any change in water chemistry or hydrology can quickly undermine breeding. Photographers and birdwatchers travel specifically to see these colonies, supporting local guides and camps near Lake Natron and other soda lakes.

Threats include upstream water extraction and proposed industrial developments that would alter lake chemistry; conservation designations and advocacy by NGOs and local communities aim to protect these critical breeding sites and the unique algae-based food webs they support.

12. Black rhinoceros

The black rhinoceros is a high-profile conservation icon and remains critically endangered; Tanzania’s role in rhino protection includes active anti-poaching units, horn removal and secure translocation to intensively managed sanctuaries. Regional numbers were decimated in the late 20th century, and current national populations are small but protected through coordinated programs.

Rhinos are ecological browsers that influence shrub and sapling dynamics, and they attract international conservation funding that benefits wider landscapes. Protection depends on vigilant anti-poaching patrols, aerial surveillance, fence-based sanctuaries and community-based incentive programs that give local people a stake in rhino survival.

Successful actions include targeted translocations into secure reserves and collaborative monitoring with partners; continued investment is needed to keep poaching pressures low and expand safe habitat where feasible.

Summary

Tanzania’s wildlife — from the giants that shape savannas to the shorebirds of alkaline lakes — underpins the country’s global profile and local economies. The Great Migration (roughly 1.2–1.5 million migrating wildebeest) remains a defining natural event, while species like the black rhino highlight ongoing conservation urgency and the payoff from intensive protection measures.

- The scale of the Great Migration is extraordinary and central to Tanzania’s ecological identity and tourism economy.

- Large-bodied species (elephants, giraffes, hippos) act as ecosystem engineers and tourism anchors, but they also create human-wildlife conflict that requires community-focused solutions.

- Apex predators and grazers together maintain savanna balance, yet many carnivores and browsers face habitat loss, snaring and competition that need monitoring and mitigation.

- Flagship species such as the black rhinoceros and lesser flamingo mobilize funding and policy action; continuing support for anti-poaching, translocations and wetland protection is essential.