Montenegro’s coastline is only about 293 km long, yet it hosts a surprising mix of Mediterranean habitats — from sandy bays to karst cliffs and the expansive Skadar Lake wetlands.

That short stretch includes long sandy beaches like Velika Plaža near Ulcinj (roughly 12 km of shoreline), rocky coves around Budva and Kotor, and river mouths that feed rich estuaries.

Below are eight emblematic species that illustrate the fauna of montenegro across marine, wetland and terrestrial zones, why each matters, and simple actions people can take to help.

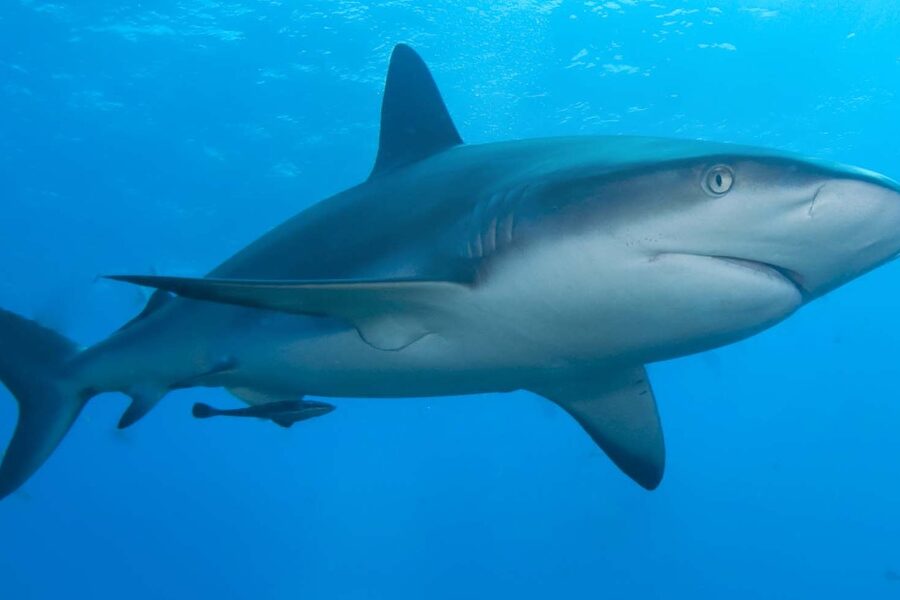

Marine and Coastal Species

Montenegro’s Adriatic waters and long sandy shores provide habitat for both resident and migratory marine life, even along a coastline of only about 293 km. Velika Plaža near Ulcinj (≈12 km long) and nearby shoals offer important foraging and occasional nesting sites for species that move between open sea, shallow bays and beaches.

Coastal development, high-season tourism, bycatch in small-scale fisheries, heavy boat traffic and light pollution on beaches threaten many species, from turtles to dolphins. Local NGOs and volunteer beach patrols—often working with park authorities and regional research groups—monitor nesting beaches, report marine mammal sightings and run outreach during summer months.

Regional protections vary by species, but measures such as boat-speed limits near key bays, dark-sky lighting on nesting beaches, and coordinated sighting networks help reduce direct human impacts while supporting responsible wildlife-watching opportunities.

1. Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus)

Small to medium-sized pods of bottlenose dolphins (typically 2–20 individuals) are regular visitors to Montenegro’s Adriatic waters, with frequent sightings in bays off Budva, near Bar and over the continental shelf. As an apex coastal predator they help keep fish communities balanced, and they also attract dolphin-watching boats that can support local ecotourism when managed responsibly. Regional survey work (for example coordinated reporting with groups like the Blue World Institute) has improved records since the 2000s, and local authorities now advise keeping 50–100 m distance, limiting chase behavior and reducing engine noise to lower disturbance and bycatch risk.

2. Loggerhead Sea Turtle (Caretta caretta)

Loggerhead sea turtles forage across the Adriatic and occasionally nest on Montenegro’s southern sandy beaches, notably around Ulcinj and the deltaic area of Ada Bojana; the long, gently sloping sand of Velika Plaža (≈12 km) creates suitable nesting substrate in some seasons. Major threats include fisheries bycatch, plastic ingestion and coastal lighting that disorients hatchlings, so volunteer nest patrols and rehabilitation centres in the region record and care for stranded animals. Practical conservation steps include implementing dark-sky measures on nesting stretches, running volunteer nest monitoring programs and promptly reporting injured or nesting turtles to local rescue networks or park authorities; writers should reference local NGO or park nest counts for recent nest totals.

3. Mediterranean Monk Seal (Monachus monachus)

The Mediterranean monk seal is among Europe’s most endangered marine mammals, with global population estimates at fewer than 700 individuals; historical records indicate the southern Adriatic once supported pockets of seals, so any contemporary sighting near Montenegro would be highly significant. Causes of decline include hunting in earlier centuries, loss of undisturbed cave haul-outs, disturbance from boats and entanglement in fishing gear, which is why current conservation focuses on protecting coastal caves, enforcing no-disturbance zones and transnational monitoring. Conservationists emphasize strict access limits to known caves, rapid reporting of sightings to coordinated networks and working with fishers to reduce gear-related mortality.

Wetland and Lake Birds (Skadar Lake Region)

Skadar Lake National Park spans a large, seasonally fluctuating wetland on the Montenegro–Albania border and is the largest lake in the Balkans, roughly 391 km² at high-water levels. Its mosaic of reedbeds, flooded islands and marshes supports dense concentrations of waterbirds during breeding and migration, and the site carries Ramsar and national park protections to help safeguard those values.

Threats around Skadar Lake include changing water levels from upstream use, invasive species and diffuse pollution, but coordinated bird-monitoring programs run by the park, BirdLife partners and NGOs have improved knowledge of breeding colonies and seasonal visitors. Local communities derive value from birdwatching tourism while also sometimes competing with waterbirds for small-scale fisheries, making collaborative management essential.

4. Dalmatian Pelican (Pelecanus crispus)

The Dalmatian pelican is a conspicuous large waterbird that uses Skadar Lake for feeding and roosting, with wingspans reaching up to about 3.5 m and adult weights reflecting their heavy build. Where pelicans nest on islands or secure islets, conservation efforts—like nest protection and minimizing disturbance—have helped local persistence and created attractions for birdwatching trips on the lake. Agencies and NGOs (Ramsar, WWF and BirdLife partners) recommend using protected routes for tours, maintaining distance from roosts and supporting island-based nest protection to reduce disturbance and accidental egg loss.

5. Pygmy Cormorant (Microcarbo pygmaeus)

The pygmy cormorant is a small, sociable cormorant common among Skadar Lake’s reedbeds and islands; colonies can swell from dozens to several hundred birds in productive seasons and they forage by diving in shallow water for small fish. Their presence is a good indicator of healthy wetland fisheries, but they remain sensitive to reedbed loss and abrupt water-level changes that flood nests or expose chicks. Park rangers and local NGOs often install nest platforms and monitor colonies, so maintaining reedbed management that balances fishing needs and bird habitat supports both livelihoods and biodiversity.

Terrestrial Reptiles and Mammals

Coastal and lowland areas of Montenegro—rocky karst, maquis scrub and riparian corridors—support a range of reptiles and semi-aquatic mammals that link sea and inland systems. These habitats around towns like Budva and Bar, and river estuaries flowing to the Adriatic, are important for species that need both terrestrial shelter and nearby water or fish resources.

Major pressures include habitat fragmentation from coastal development, agricultural intensification, roads that increase mortality and invasive plants that change shrub structure. Simple land-management choices—retaining hedgerows, limiting roadside lighting and protecting river buffers—benefit tortoises, geckos and otters alike.

6. Hermann’s Tortoise (Testudo hermanni)

Hermann’s tortoise lives in coastal maquis and lowland scrub around places like Budva and Bar, where open sunny clearings, rocky outcrops and dense shrub provide feeding and shelter; they are herbivores with long lifespans and depend on a mosaic of habitats for nesting and foraging. Threats include collection for the pet trade, road mortality and loss of habitat to development, so regional awareness campaigns and protected-area policies aim to reduce illegal take and maintain habitat corridors. Landowners can help by retaining rock piles, low hedgerows and patches of scrub, which support tortoises and a host of other small Mediterranean species.

7. Mediterranean House Gecko (Hemidactylus turcicus)

The Mediterranean house gecko is a small, nocturnal insectivore often seen on old stone walls, ruins and coastal hotels in towns such as Kotor, where it silently hunts moths and mosquitoes attracted to lights. It plays a handy ecological role as natural pest control around homes and seaside restaurants, and it tolerates human presence better than many reptiles. Still, heavy pesticide use and intense night-time lighting reduce insect prey and can disrupt gecko activity, so simple measures like reducing pesticides and using softer, directional lighting help maintain local populations.

8. European Otter (Lutra lutra)

The European otter signals healthy river, estuary and lagoon systems and has been recorded around river mouths entering the Adriatic and in coastal lagoons near Ulcinj and Bar. Otters feed largely on fish and are territorial and mainly active at dusk and night, so they need clean water, unobstructed river corridors and places to den along banks. Threats include water pollution, barriers from poorly sited hydropower or weirs, and entanglement in fishing gear; protecting riparian buffers, reducing pollutants and promoting safe fishery practices benefits otters and improves water quality for people too.

Summary

Montenegro packs a lot of biodiversity into a short coastline and a large, variable lake basin, bringing together marine, wetland and terrestrial species that are both charismatic and vulnerable.

- Even with just ~293 km of coast, habitats from Velika Plaža (~12 km) to karst cliffs and Skadar Lake (~391 km² at high water) support a wide range of species.

- Conservation wins rely on managing tourism, reducing bycatch and light pollution, and protecting reedbeds and river corridors.

- Local monitoring—NGOs, park staff and volunteer patrols—has improved records for dolphins, turtles, pelicans and cormorants, and made targeted protection possible.

- Get involved: respect boat and beach rules, report sightings to local groups, and support Skadar Lake National Park and local conservation organizations to help safeguard the region’s wildlife and habitats.