In 2020 Denmark ordered the cull of roughly 17 million farmed mink after SARS-CoV-2 mutations were detected in animals — a dramatic event that pushed minks into global headlines (BBC report).

That episode highlights how minks are entwined with people in ways weasels rarely are, and many people conflate these animals. Confusion about minks vs weasels leads to misunderstandings about their ecology, management, and conservation. Although both are mustelids, they differ markedly in anatomy, habitat use, behavior, and human relationships; the sections below explain six clear differences and why they matter.

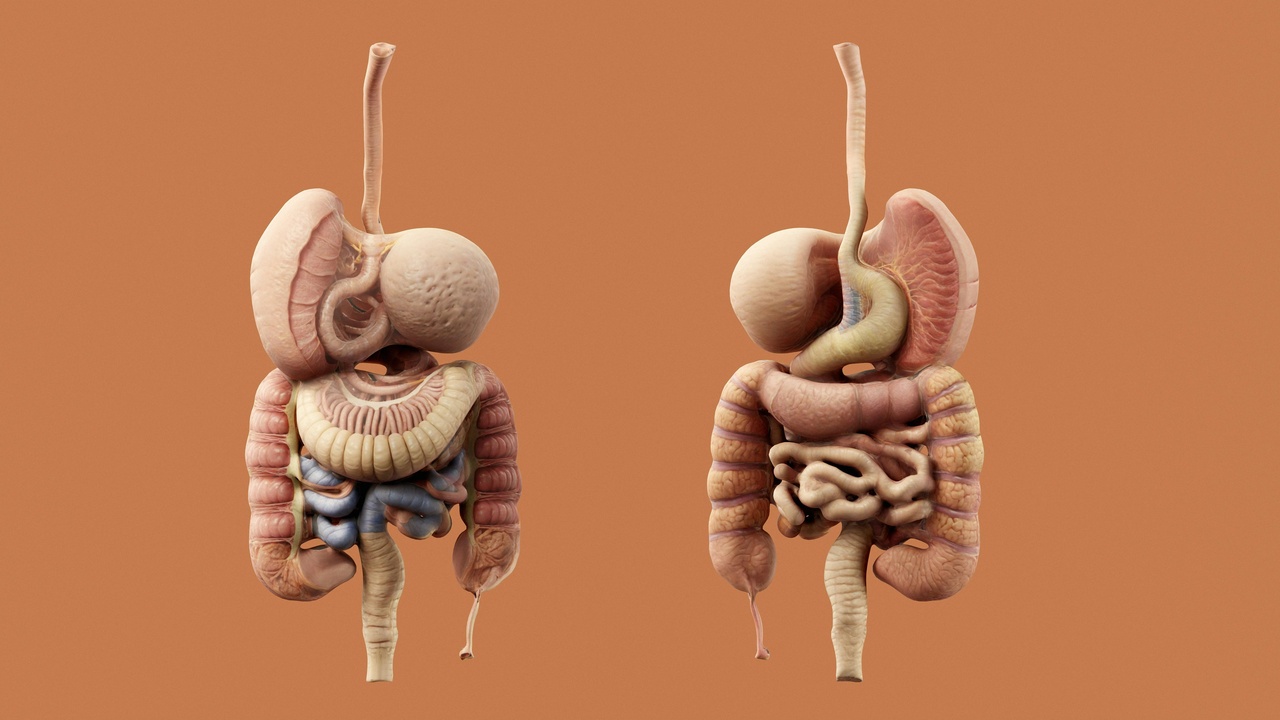

Physical and anatomical differences

Body size, fur density, and limb adaptations mirror different lifestyles: minks are built for semi-aquatic hunting while most weasels are tiny, terrestrial specialists. Below are two core anatomical contrasts that explain those lifestyles.

1. Size and body proportions

Minks are generally larger and heavier than most weasels and have relatively longer tails. For example, American mink (Neovison vison) males commonly weigh about 700–1,600 g and measure roughly 30–45 cm in body length, plus an 18–25 cm tail; by contrast, the least weasel (Mustela nivalis) can weigh as little as 25–250 g with body lengths of about 11–26 cm. Sexual dimorphism is typical in both groups, with males noticeably larger than females.

Those size differences shape hunting style: the larger mink can take fish and crustaceans and handle bigger prey, while the diminutive weasel fits into burrows and chases mice and voles in tight tunnels. This contrast helps explain why you’ll more often see mink tracks along shorelines and weasel sign around fields and burrows.

2. Fur, feet, and swimming adaptations

Mink coats have a dense underfur plus oily guard hairs that shed water, and their feet are slightly flattened—features that aid swimming and insulation in cold water. That water-resistant pelt is a big reason American mink became the primary species in the fur trade.

Weasels, by contrast, have sleeker fur optimized for stealth and rapid terrestrial movement rather than prolonged water exposure. Functionally, this means minks regularly hunt aquatic prey and are competent swimmers (able to swim and dive for short distances), whereas weasels rely on speed, agility, and slender bodies to pursue rodents in grass, brush, and underground tunnels.

Behavior, diet, and ecological roles

Behavioral ecology diverges: minks are opportunistic, semi-aquatic predators often tied to riparian zones, while weasels are high-metabolism terrestrial hunters focused on small mammals. The following two points describe diet and hunting strategies with ecological consequences.

3. Diet: fish and amphibians versus rodents

The primary dietary difference is straightforward: minks take more fish, amphibians, crustaceans and water-edge birds, while weasels specialize on small mammals such as mice, voles, and shrews. In riparian habitats, studies frequently find fish and amphibians make up a majority of wild mink diets; by contrast, weasels may consume an extremely high proportion of their body mass each day—often cited as roughly 30–50% of their weight—to meet energetic demands.

Those diets have ecological effects. Escaped American mink have been documented preying on water voles and ground-nesting birds in Europe, contributing to local declines in vulnerable populations. Meanwhile, weasels can suppress vole outbreaks on farmland, making them useful predators in some agricultural systems (regional variation applies).

4. Hunting tactics and territory use

Minks typically hunt along waterways, using swimming and ambush to catch prey, while weasels use speed, stealth, and the ability to enter burrows to extract rodents. Activity patterns are variable—many minks are crepuscular or nocturnal near water, and many weasels are active day or night depending on prey availability.

Home-range structure reflects these tactics: mink territories are often linear along river corridors and can span several kilometers of shoreline, whereas weasel home ranges are much smaller—frequently only a few hectares—concentrated where rodents are abundant. Those spatial differences affect vulnerability to habitat fragmentation, trapping, and human encounters.

Human interactions, management, and conservation

Humans engage with minks and weasels very differently: one group has driven a global industry and invasive impacts, while the other is often overlooked or treated as a pest. The next two points cover farming and invasion issues, plus legal and conservation outcomes.

5. Relationship with people: fur farming and invasive impacts

American mink is the primary species in global fur farming; large-scale captive production and escape events led to established feral populations in parts of Europe and South America after introductions beginning in the early 20th century. A dramatic management moment came in 2020 when Denmark culled about 17 million farmed mink to control SARS-CoV-2 mutations linked to mink farms.

Escaped mink can severely affect native species—water vole declines in parts of Europe are a well-documented example—and governments have used eradication campaigns, tighter biosecurity, and regulatory changes to respond. Policy responses vary from outright farm bans to stricter containment and monitoring (see national wildlife agencies and FAO statistics for country-level figures).

6. Legal status, conservation, and cultural perceptions

Certain mustelids receive protection while others are regulated as pests. The European mink (Mustela lutreola), for example, is listed as threatened on the IUCN Red List and is the focus of reintroduction and captive-breeding programs (IUCN). By contrast, many weasel species maintain stable populations and may be legally trapped or controlled in some regions to protect poultry or game.

Cultural perceptions shape policy: minks are associated with fashion, controversy, and large-scale farming, while weasels often appear in folklore or are tolerated for rodent control. That leads to different legal outcomes—protected lists and recovery plans for some species, trapping regulations or pest rules for others—so check local wildlife authorities for region-specific guidance.

Summary

- Minks are larger, semi-aquatic, and built for swimming and fishing; many weasels are tiny, terrestrial rodent specialists.

- Key numbers to remember: the 2020 Denmark cull (~17 million farmed mink), American mink males ~700–1,600 g, least weasels 25–250 g, and weasels may eat ~30–50% of their body weight daily.

- Different diets and territory use produce different ecological impacts—minks can harm water-edge species; weasels often help control rodent populations.

- When identifying in the field, use size, tail length, and habitat: see a small, slender mustelid in a burrow or field and you’re likely looking at a weasel; see a larger animal along water with a longer tail and dense, water-repellent fur and you’re likely seeing a mink.

- For management or conservation action, consult IUCN species accounts or your national wildlife agency and support local conservation groups working on vulnerable mustelids.