A 19th-century fur-trapping map of North America shows beavers and river otters in overlapping river systems — animals humans once valued for pelts that shaped economies and habitats.

Today those same rivers are focal points for rewilding projects, backyard stream stewardship, and debates about how to manage aquatic wildlife. People often mix up these semi-aquatic mammals or assume they perform the same role in a watershed.

Otters and beavers look similar at a glance, but they differ in anatomy, behavior, ecology, and the ways they shape landscapes; understanding those differences clarifies why each species matters in its own right.

The rest of the article lists exactly six key differences between otters and beavers and explains why each difference matters for ecosystems and people. River otters commonly live about 8–9 years in the wild, which helps set expectations for population recovery timelines.

Physical and Anatomical Differences

Body form reflects lifestyle: beavers are built for digging and construction while otters are built for pursuit and maneuvering in water. Look for tail shape, body profile, and paw structure when identifying animals in the field.

1. Body shape and swimming adaptations

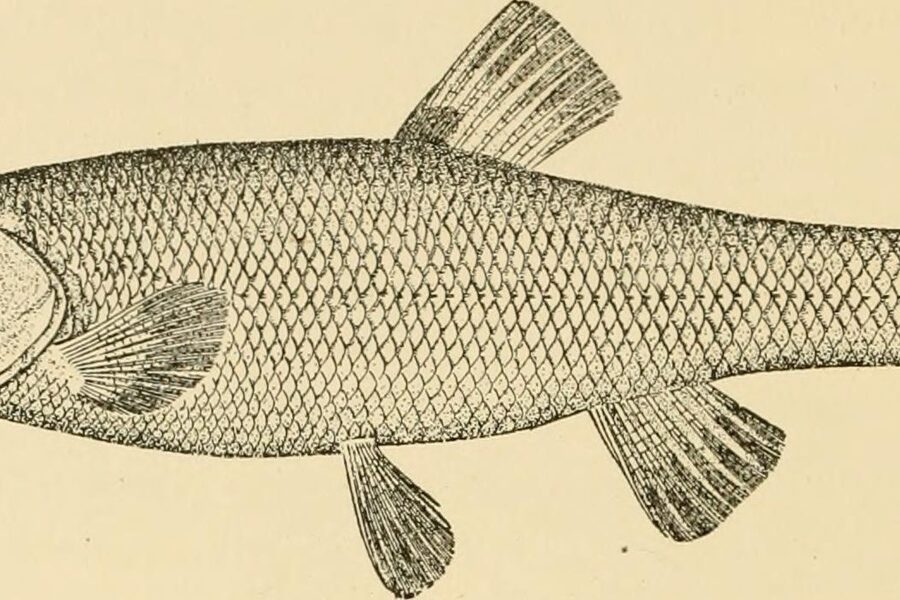

Otters are streamlined and built for speed and agility; North American river otters (Lontra canadensis) typically weigh about 5–14 kg and measure roughly 0.9–1.2 m including the tail (state and provincial fact sheets). They have long, tapered tails, webbed feet, and flexible spines for rapid turns and underwater chases. By contrast, North American beavers (Castor canadensis) are stockier, generally 11–30 kg with body lengths up to ~1.2 m (not including the tail). Beavers have broad, flat, paddle-like tails and powerful hindquarters designed for pushing logs, anchoring dams, and stability in slow water. In the field, tail shape (tapered vs. flattened), gait on land (otters bound or gallop; beavers lumber), and the presence of gnaw marks on trees are reliable ID clues (wildlife agency field guides).

2. Fur, teeth, and sensory adaptations

Fur structure, dentition, and sensory gear match each species’ niche. Otters have extremely dense underfur and frequent grooming to trap air for insulation; sea otter studies report extraordinarily high hair densities (used cautiously as a comparative example for insulating fur). River otters also rely on thick, sleek fur but groom less obsessively than sea otters. Beavers have layered fur with long guard hairs and an oily, water-repellent outer coat suited to sitting in ponds for long periods.

Dental differences are striking: beavers are rodents with ever-growing incisors; the orange hue of beaver front teeth comes from iron-rich enamel and those teeth can fell trees and strip bark repeatedly. Otter dentition is adapted for carnivory—sharp carnassials and molars for crushing shells and fish bones. Sensory adaptations differ too: otters use highly sensitive whiskers (vibrissae) to detect fish in murky water, while beavers rely on tactile cues and hearing when working at night. These traits affect handling in rehabilitation, trapping histories, and field forensic signs like tooth marks on wood (marine mammal and rodent physiology sources).

Behavior and Social Structure

Behaviorally, otters are more mobile and play-oriented; beavers are deliberate, territorial ecosystem engineers. Activity patterns, foraging strategies, and family structure all follow from those broad contrasts.

3. Foraging and diet differences

Otters are primarily carnivorous piscivores: river otters feed on fish, crustaceans, amphibians and occasionally small mammals, while sea otters consume large numbers of invertebrates. Sea otter studies estimate adults eat roughly 20–30% of their body weight per day, a useful comparative benchmark for how energy-intensive carnivory can be. River otters can significantly influence local fish populations, especially in small streams or lakes where they concentrate hunting.

Beavers are herbivores that eat bark, cambium, and aquatic plants. They fell trees like willow and aspen to access food and building materials and create food caches of branches for winter. A single beaver family can girdle multiple trees along a stream bank over a season, reshaping riparian vegetation. These dietary differences explain why otters impact fisheries and beavers reshuffle forest composition and shoreline vegetation (conservation agency reports and field studies).

4. Social structure and territory

Otters show social flexibility: individuals range from solitary hunters to small groups. River otter family groups are commonly 2–5 animals, often a female with her young or small sibling groups observed playing together. Activity timing varies with food availability and human disturbance; they can be active day or night.

Beavers form stable, territorial family units—typically 4–8 individuals—that cooperate to maintain dams, lodges, and food stores. Territories are actively defended with scent mounds, tail slaps, and vocalizations; boundaries are monitored and repaired regularly. From a management perspective, beaver social cohesion makes colony-level interventions (flow devices, relocation) effective, whereas otter issues tend to be addressed at the population or habitat scale (wildlife manager observations).

Ecological Roles and Human Interactions

Although both change ecosystems, they do so differently: beavers physically reconfigure waterways by building structures, while otters influence food webs through predation. Comparing otters vs beavers side-by-side highlights complementary but distinct ecosystem services and management needs.

5. Landscape engineering: dams, lodges, and habitat creation

Beavers are classic ecosystem engineers that convert flowing streams into ponds and wetlands by building dams and lodges. These ponds increase habitat complexity, create breeding sites for amphibians, and support aquatic plants and bird life. Regional projects—such as the River Otter Beaver Trial in Devon, U.K., and numerous western U.S. watershed restorations—have documented restored marshes, improved floodplain connectivity, and greater seasonal water retention after beaver activity.

Otters do not construct long-lived structures; instead, they use riparian connectivity and predation to shape species composition. For example, sea otter recoveries have been linked to kelp forest rebounds through predation on sea urchins—a trophic effect rather than physical engineering. In rivers, otters help maintain healthy fish populations and serve as mobile indicators of habitat quality, but they rely on the physical alterations beavers and geomorphology provide.

6. Conservation, conflicts, and human uses

Both species suffered dramatic declines in the fur trade era: millions of beaver pelts and vast numbers of otters were taken in the 18th–19th centuries, with sea otters reduced to a few hundred individuals by the early 20th century in some regions. Since then, legal protections and reintroduction efforts have enabled many local recoveries, though status varies by region (IUCN and national wildlife agencies).

Human-wildlife conflicts differ. Beavers can cause localized flooding, tree loss, or infrastructure damage; practical mitigations include flow devices (e.g., the “beaver deceiver” or engineered culvert protections), tree wrapping, and targeted relocation. Otters can conflict with fisheries or fish farms, and solutions focus on deterrents, habitat buffering, and cooperative fisheries management. Both species provide benefits: beaver wetlands improve water storage and biodiversity, while otters indicate clean waterways and attract ecotourism. Contact your state wildlife agency or local NGO for site-specific guidance and to report sightings.

Summary

- Body form: otters are streamlined pursuit predators; beavers are heavyset builders with paddle tails.

- Fur and teeth: otter fur and whiskers support hunting; beaver incisors grow continuously and enable tree-felling.

- Behavior: otters hunt and move widely; beavers live in territorial family units that maintain dams and lodges.

- Ecological role: beavers engineer wetlands and hydrology; otters shape food webs and act as indicators of healthy water.

- Management: use species-specific strategies (flow devices and exclusion for beavers; habitat buffering and collaborative fisheries plans for otters); report sightings and work with local wildlife programs.