The Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) — a 250 km long, roughly 4 km wide buffer created in 1953 — has unintentionally become one of the Korean Peninsula’s richest wildlife refuges. Left largely undisturbed for seven decades, its patchwork of forests, wetlands and grasslands shelters species that have become rare elsewhere on the peninsula. South Korea also manages 22 national parks, from Seoraksan’s granite spires to Hallasan’s volcanic summit on Jeju, that add formal protection to this mosaic of habitats.

You should care because these places supply clear benefits: they maintain biodiversity, anchor cultural identities, and support livelihoods through eco-tourism, fisheries and flood protection. Conservation here matters globally — migratory birds cross continents using Korean tidal flats, while mountain forests sustain mammals that help regenerate woodlands. The wildlife of south korea is surprisingly rich, and the stories that follow show why eight species deserve attention for science, culture and local communities.

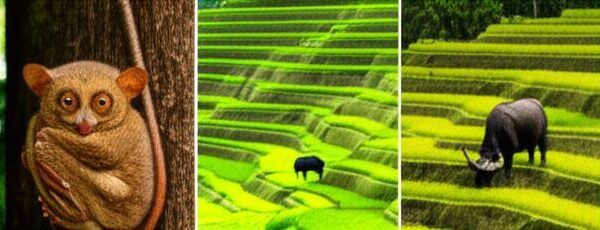

Mountain and Forest Mammals

Korea’s rugged spine — the Baekdudaegan range and high parks like Seoraksan, Jirisan and Hallasan — shelter larger mammals that need continuous forest and steep refuges. These montane woodlands are critical for seed dispersers, predators and species found at the edge of their ranges.

Protected areas and the accidental protection offered by the DMZ help preserve populations, but threats persist: roadbuilding fragments habitat, poaching still occurs in remote valleys, and warming climates are shifting suitable ranges uphill. The Korea National Park Service (K-NPS) runs monitoring and rewilding pilots to reconnect forest blocks and reduce human-wildlife conflict.

Conservation work here blends science and local stewardship: camera-trap monitoring, ranger patrols, community education and targeted restoration. Below are three mammals that illustrate why these mountains matter.

1. Asiatic Black Bear (Moon Bear) — Ursus thibetanus

The Asiatic black bear, known regionally as the moon bear for the pale crescent on its chest, is remarkable in Korea both culturally and ecologically. Bears figure in Korean folklore and modern awareness campaigns, yet populations suffered steep declines through the 20th century.

Globally the species is listed as Vulnerable by IUCN, and Korea’s remnant populations are fragmented and small. K-NPS and university teams have documented bears using remote camera traps in Jirisan and along the Baekdudaegan ridgeline (camera-trap records increased in the 2010s as monitoring intensified), providing baseline data for conservation planning.

Practical conservation includes conflict-mitigation measures (livestock enclosures and community compensation), rehabilitation centers that care for injured bears, and public education to reduce illegal capture. Bears also boost ecotourism interest when sightings or signs are managed responsibly, and as seed dispersers they play a key role in forest regeneration.

2. Korean Goral — Naemorhedus caudatus

The Korean goral is a sure-footed, cliff-loving ungulate that clings to steep slopes and rocky outcrops. Its compact body and specialized hooves let it exploit habitats few other mammals use, making it an indicator of intact montane terrain.

Goral populations are patchy across the Baekdudaegan and Seoraksan ranges and are vulnerable to poaching and disturbance from poorly sited trails. Seoraksan National Park regularly records goral sightings along high ridgelines, and park managers adjusted trail routing and seasonal closures in the 2000s to reduce disturbance near known concentrations.

For hikers and wildlife watchers, gorals are a draw; for managers, they are useful monitors of habitat quality. Local ranger patrol programs and targeted anti-poaching enforcement have helped stabilize some populations where implemented.

3. Korean Water Deer — Hydropotes inermis (the ‘vampire deer’)

The Korean water deer is instantly recognizable for its prominent upward-pointing canine tusks and lack of antlers, earning it the nickname ‘vampire deer’ in popular media. Unlike the more secretive mountain species, water deer thrive near wetlands, river edges and even suburban green belts.

They tolerate fragmented landscapes better than many ungulates, which leads to frequent human-wildlife interactions: garden browsing, agricultural damage and collisions on roads near park boundaries. Road mortality hotspots are regularly reported around national park exits and Seoul’s outer green belts, and citizen science apps now collect many local sightings.

Managing the water deer illustrates the urban-wildlife interface: measures include better signage and fencing on roads, community reporting platforms, and using deer presence for public education about coexistence.

Wetlands and Coastal Birds

The west coast’s tidal flats and southern estuaries (places like Suncheon Bay, Cheonsu Bay and the islands near the southwest) are essential stopovers and wintering sites on the East Asian–Australasian Flyway. These intertidal zones support huge flocks of shorebirds, breeding waterbirds, and dense invertebrate life that sustains them.

South Korea hosts several Ramsar-listed wetlands and coastal reserves, and local communities often lead protection and tourism efforts. Yet large-scale land reclamation, most famously at Saemangeum, has altered mudflat habitat and sparked national and international debate about balancing development and biodiversity.

Community stewardship, wetland restoration projects and legal protections have mitigated some losses. Birdwatching generates local income through guided tours and festivals, creating incentives to maintain healthy tidal ecosystems.

4. Black-faced Spoonbill — Platalea minor

The black-faced spoonbill is emblematic of Korea’s tidal-flat conservation challenge: globally threatened and heavily dependent on tidal foraging grounds along Korea’s coastlines. Historically numbered under 4,000 individuals worldwide, it remains a high-priority species for flyway conservation.

Korea provides key breeding and feeding sites; Suncheon Bay is one notable monitoring location where regular counts and volunteer surveys track seasonal numbers. Local volunteers and NGOs coordinate roost counts in winter, and cross-border cooperation with China, Taiwan and Japan supports the species across its range.

Black-faced spoonbills also fuel a modest birdwatching economy: guided tours and interpretive centers at wetlands translate conservation into jobs for local residents while reinforcing protective measures.

5. Red-crowned Crane — Grus japonensis

The red-crowned crane is one of East Asia’s best-known cultural icons and a conservation flagship in Korea. Revered in folklore and art, cranes attract tourists to wetland viewing sites and interpretive centers in the southwest and near Suncheon.

Conservation actions include wetland restoration, protected wintering grounds, and captive-breeding and release programs that support small local populations. These efforts benefit broad wetland ecosystems, improving habitat for fish, invertebrates and other bird species.

Despite successes, cranes still face habitat loss and disturbance. Continued investment in protected wetlands and coordination with neighboring countries remain essential for long-term survival.

6. White-naped Crane — Antigone vipio (migratory visitor)

The white-naped crane is a seasonal visitor that relies on Korean wetlands and the DMZ buffer as stopovers during migration. Large winter counts in certain estuaries and DMZ wetlands can number in the hundreds, making these sites internationally significant.

Migration timing typically peaks in late autumn and returns in spring, and citizen science counts and winter festivals around crane concentrations help raise awareness while contributing data to flyway conservation plans.

Monitoring seasonal numbers in the DMZ and adjacent Ramsar sites informs international strategies for protecting critical stopover habitats across East Asia.

Marine Species and Small Carnivores

Korea’s coastal seas, estuaries and offshore islands host marine mammals and small carnivores whose fortunes reflect ocean health and coastal management. Fisheries interactions, bycatch in gillnets, and coastal pollution are the main threats these species face.

Local fishing communities, academic groups and NGOs run mitigation trials and monitoring programs that combine acoustic surveys, bycatch reduction gear tests and protected areas around important island habitats.

These efforts are pragmatic: healthy marine mammals and predators indicate robust fisheries, while island conservation projects protect breeding seabirds and endemic species.

7. East Asian Finless Porpoise — Neophocaena asiaeorientalis

The East Asian finless porpoise is a shy, nearshore cetacean seen in Korean waters, and it serves as an indicator of coastal ecosystem health. Subpopulations in the Yellow Sea and adjacent waters are vulnerable to gillnet bycatch and habitat degradation.

Recent acoustic monitoring and visual survey projects conducted by universities and NGOs have helped estimate local densities and identify high-use areas. Acoustic surveys off Korea’s west coast have revealed persistent porpoise presence but also highlighted zones where bycatch risk is high.

Practical measures include bycatch-reduction trials, gear modification workshops with fishers, and marine-noise management around important foraging grounds. Porpoise-focused ecotours also provide alternative income and raise public support for protective measures.

8. Korean Leopard Cat — Prionailurus bengalensis euptilura

The leopard cat is Korea’s small wild felid, often overlooked but ecologically valuable as a mesopredator that helps regulate rodent populations. It occupies forest edges, agricultural mosaics and, on Jeju Island, more contiguous forest habitat.

Camera-trap and genetic studies in Gyeonggi Province and Jeju have documented leopard cat presence and movement corridors, revealing threats from road mortality and habitat loss around expanding farmland and suburbs.

Conservation actions combine roadside fencing in hot-spot areas, outreach to farmers about livestock protections, and citizen camera-trap programs that engage nature enthusiasts while producing valuable distribution data.

Summary

South Korea’s landscapes — the DMZ refuge, 22 national parks, tidal flats and coastal islands — sustain species of global and cultural importance. Effective conservation combines protected areas, community stewardship and science-driven monitoring.

- DMZ and national parks provide unexpected refuges for mammals and birds across Korea’s mountains and wetlands.

- Tidal flats (Ramsar sites like Suncheon Bay) are critical for migratory shorebirds, including the globally threatened black-faced spoonbill (historically under 4,000 individuals).

- Practical conservation blends camera-trap monitoring, acoustic surveys, bycatch-reduction trials and local stewardship to deliver ecological and economic benefits.

- Flagship species — the Asiatic black bear, red-crowned crane, finless porpoise and leopard cat — help focus conservation that also safeguards fisheries, flood protection and cultural values.

Support trusted local NGOs, visit wetlands and parks responsibly, and consider contributing sightings to citizen-science platforms to help track these species. Small actions add up for the wildlife and communities that depend on Korea’s remarkable natural heritage.