Local co-management arrangements that integrate Indigenous knowledge with science have proved effective in many areas for setting quotas, timing hunts and identifying sensitive habitats.

Industrial noise and shipping can interfere with echolocation and cause displacement from feeding areas. Regulated subsistence hunts remain an important local practice; across Greenland and Canadian waters, catches typically number in the hundreds to a few thousand animals annually, managed regionally to balance cultural needs and population health.

Local co-management arrangements that integrate Indigenous knowledge with science have proved effective in many areas for setting quotas, timing hunts and identifying sensitive habitats.

10. Cultural importance and research value: Indigenous knowledge and scientific insights

Narwhals are central to Inuit life—for food, tools (including historically important tusks) and seasonal calendars that guide travel and hunting. Community knowledge about migration timing and fjord fidelity complements scientific data.

Collaborative programs combine tagging, acoustics and genetics with local monitoring—community-led aerial counts and shore-based observations are common. Museum tusk records have also been used in historical analyses of trade and distribution.

Together, Indigenous stewardship and international science provide the best path to informed management and long-term conservation of narwhals and the Arctic systems they help reveal.

Summary

- The tusk is unique—an elongated canine with sensory capacity and social roles, and a reason narwhals entered European lore.

- Narwhals are deep-diving, ice-adapted predators (dives commonly >800 m) that link surface and deep food webs and rely on thick blubber for insulation and energy.

- Populations are regionally variable (global estimates on the order of ~170,000) and vulnerable to sea-ice loss, noise and industrial activity; sustainable, locally led management matters.

- Indigenous knowledge and scientific research—tagging, acoustics and genetics—are both essential to understanding narwhal ecology and guiding conservation.

Learn more by reading IUCN and NOAA summaries, supporting reputable Arctic research groups, and exploring Indigenous perspectives on narwhal stewardship.

Because narwhals return to the same fjords and have low reproductive rates, local declines can be slow to reverse, so regional management and reliable monitoring are essential (IUCN, WWF and national agencies provide ongoing assessments).

9. Threats: climate change, industrial activity and hunting pressures

Key threats include loss of sea ice from climate warming, increased ship traffic and noise, oil and gas exploration, and subsistence hunting. Each pressure affects narwhals differently depending on location and timing.

Summer Arctic sea-ice minimums have declined substantially since satellite records began in 1979—by roughly 40% in September extent—which alters habitat and can shift prey deeper or poleward. Changes in prey distribution force narwhals to expend more energy or alter long-established routes.

Industrial noise and shipping can interfere with echolocation and cause displacement from feeding areas. Regulated subsistence hunts remain an important local practice; across Greenland and Canadian waters, catches typically number in the hundreds to a few thousand animals annually, managed regionally to balance cultural needs and population health.

Local co-management arrangements that integrate Indigenous knowledge with science have proved effective in many areas for setting quotas, timing hunts and identifying sensitive habitats.

10. Cultural importance and research value: Indigenous knowledge and scientific insights

Narwhals are central to Inuit life—for food, tools (including historically important tusks) and seasonal calendars that guide travel and hunting. Community knowledge about migration timing and fjord fidelity complements scientific data.

Collaborative programs combine tagging, acoustics and genetics with local monitoring—community-led aerial counts and shore-based observations are common. Museum tusk records have also been used in historical analyses of trade and distribution.

Together, Indigenous stewardship and international science provide the best path to informed management and long-term conservation of narwhals and the Arctic systems they help reveal.

Summary

- The tusk is unique—an elongated canine with sensory capacity and social roles, and a reason narwhals entered European lore.

- Narwhals are deep-diving, ice-adapted predators (dives commonly >800 m) that link surface and deep food webs and rely on thick blubber for insulation and energy.

- Populations are regionally variable (global estimates on the order of ~170,000) and vulnerable to sea-ice loss, noise and industrial activity; sustainable, locally led management matters.

- Indigenous knowledge and scientific research—tagging, acoustics and genetics—are both essential to understanding narwhal ecology and guiding conservation.

Learn more by reading IUCN and NOAA summaries, supporting reputable Arctic research groups, and exploring Indigenous perspectives on narwhal stewardship.

Predictable movements matter: they guide subsistence hunting schedules, enable focused scientific monitoring, and create opportunities to protect key habitat during critical life stages.

Human interactions and conservation

Narwhals are tightly linked to human cultures, especially Inuit communities that rely on them for food, materials and seasonal knowledge. Conservation involves local stewardship, national agencies and international bodies working together.

8. Population size and conservation status: limited populations with regional differences

Global population estimates are on the order of a few hundred thousand; a commonly cited figure is roughly 170,000 individuals worldwide, though regional abundances vary and estimates carry uncertainty.

The IUCN currently lists narwhals as Near Threatened, reflecting region-specific pressures and the species’ vulnerability due to slow reproduction and site fidelity. Some aggregations—like West Greenland and parts of Canada—are closely monitored through combined scientific and Indigenous programs.

Because narwhals return to the same fjords and have low reproductive rates, local declines can be slow to reverse, so regional management and reliable monitoring are essential (IUCN, WWF and national agencies provide ongoing assessments).

9. Threats: climate change, industrial activity and hunting pressures

Key threats include loss of sea ice from climate warming, increased ship traffic and noise, oil and gas exploration, and subsistence hunting. Each pressure affects narwhals differently depending on location and timing.

Summer Arctic sea-ice minimums have declined substantially since satellite records began in 1979—by roughly 40% in September extent—which alters habitat and can shift prey deeper or poleward. Changes in prey distribution force narwhals to expend more energy or alter long-established routes.

Industrial noise and shipping can interfere with echolocation and cause displacement from feeding areas. Regulated subsistence hunts remain an important local practice; across Greenland and Canadian waters, catches typically number in the hundreds to a few thousand animals annually, managed regionally to balance cultural needs and population health.

Local co-management arrangements that integrate Indigenous knowledge with science have proved effective in many areas for setting quotas, timing hunts and identifying sensitive habitats.

10. Cultural importance and research value: Indigenous knowledge and scientific insights

Narwhals are central to Inuit life—for food, tools (including historically important tusks) and seasonal calendars that guide travel and hunting. Community knowledge about migration timing and fjord fidelity complements scientific data.

Collaborative programs combine tagging, acoustics and genetics with local monitoring—community-led aerial counts and shore-based observations are common. Museum tusk records have also been used in historical analyses of trade and distribution.

Together, Indigenous stewardship and international science provide the best path to informed management and long-term conservation of narwhals and the Arctic systems they help reveal.

Summary

- The tusk is unique—an elongated canine with sensory capacity and social roles, and a reason narwhals entered European lore.

- Narwhals are deep-diving, ice-adapted predators (dives commonly >800 m) that link surface and deep food webs and rely on thick blubber for insulation and energy.

- Populations are regionally variable (global estimates on the order of ~170,000) and vulnerable to sea-ice loss, noise and industrial activity; sustainable, locally led management matters.

- Indigenous knowledge and scientific research—tagging, acoustics and genetics—are both essential to understanding narwhal ecology and guiding conservation.

Learn more by reading IUCN and NOAA summaries, supporting reputable Arctic research groups, and exploring Indigenous perspectives on narwhal stewardship.

Sound is central to narwhal survival: noise from ships or industry can mask echolocation signals and displace animals from important feeding or breathing sites.

7. Social structure and migration: pods, seasonal movements and ice fidelity

Narwhals form variable pods—small groups in winter and larger aggregations in summer fjords. Hunters and scientists report typical winter groups of a few to a few dozen, while summer gatherings can number hundreds in favored coastal bays.

Seasonal migrations move narwhals from offshore, ice-edge wintering grounds into protected fjords and estuaries for summer calving and feeding. Tagging and Inuit knowledge show many populations return to the same fjords year after year.

Predictable movements matter: they guide subsistence hunting schedules, enable focused scientific monitoring, and create opportunities to protect key habitat during critical life stages.

Human interactions and conservation

Narwhals are tightly linked to human cultures, especially Inuit communities that rely on them for food, materials and seasonal knowledge. Conservation involves local stewardship, national agencies and international bodies working together.

8. Population size and conservation status: limited populations with regional differences

Global population estimates are on the order of a few hundred thousand; a commonly cited figure is roughly 170,000 individuals worldwide, though regional abundances vary and estimates carry uncertainty.

The IUCN currently lists narwhals as Near Threatened, reflecting region-specific pressures and the species’ vulnerability due to slow reproduction and site fidelity. Some aggregations—like West Greenland and parts of Canada—are closely monitored through combined scientific and Indigenous programs.

Because narwhals return to the same fjords and have low reproductive rates, local declines can be slow to reverse, so regional management and reliable monitoring are essential (IUCN, WWF and national agencies provide ongoing assessments).

9. Threats: climate change, industrial activity and hunting pressures

Key threats include loss of sea ice from climate warming, increased ship traffic and noise, oil and gas exploration, and subsistence hunting. Each pressure affects narwhals differently depending on location and timing.

Summer Arctic sea-ice minimums have declined substantially since satellite records began in 1979—by roughly 40% in September extent—which alters habitat and can shift prey deeper or poleward. Changes in prey distribution force narwhals to expend more energy or alter long-established routes.

Industrial noise and shipping can interfere with echolocation and cause displacement from feeding areas. Regulated subsistence hunts remain an important local practice; across Greenland and Canadian waters, catches typically number in the hundreds to a few thousand animals annually, managed regionally to balance cultural needs and population health.

Local co-management arrangements that integrate Indigenous knowledge with science have proved effective in many areas for setting quotas, timing hunts and identifying sensitive habitats.

10. Cultural importance and research value: Indigenous knowledge and scientific insights

Narwhals are central to Inuit life—for food, tools (including historically important tusks) and seasonal calendars that guide travel and hunting. Community knowledge about migration timing and fjord fidelity complements scientific data.

Collaborative programs combine tagging, acoustics and genetics with local monitoring—community-led aerial counts and shore-based observations are common. Museum tusk records have also been used in historical analyses of trade and distribution.

Together, Indigenous stewardship and international science provide the best path to informed management and long-term conservation of narwhals and the Arctic systems they help reveal.

Summary

- The tusk is unique—an elongated canine with sensory capacity and social roles, and a reason narwhals entered European lore.

- Narwhals are deep-diving, ice-adapted predators (dives commonly >800 m) that link surface and deep food webs and rely on thick blubber for insulation and energy.

- Populations are regionally variable (global estimates on the order of ~170,000) and vulnerable to sea-ice loss, noise and industrial activity; sustainable, locally led management matters.

- Indigenous knowledge and scientific research—tagging, acoustics and genetics—are both essential to understanding narwhal ecology and guiding conservation.

Learn more by reading IUCN and NOAA summaries, supporting reputable Arctic research groups, and exploring Indigenous perspectives on narwhal stewardship.

Acoustic and tag studies reveal repeated deep-forage patterns: day-to-day trips to the same slope features. That specialization makes narwhals sensitive to shifts in prey depth or location caused by warming waters and changing oceanographic conditions.

6. Echolocation and sensory abilities: navigating under ice

Narwhals use echolocation clicks, whistles and pulsed calls to navigate, find prey and communicate beneath ice where light is limited. Echolocation lets them detect prey and cracks in the ice to reach air.

Acoustic monitoring has documented dozens of distinct call types and broadband clicks adapted to complex, ice-covered habitats (see NOAA and IWC acoustic studies). The tusk’s sensory capacity likely complements sonar by providing direct, close-range information about water chemistry and local vibrations.

Sound is central to narwhal survival: noise from ships or industry can mask echolocation signals and displace animals from important feeding or breathing sites.

7. Social structure and migration: pods, seasonal movements and ice fidelity

Narwhals form variable pods—small groups in winter and larger aggregations in summer fjords. Hunters and scientists report typical winter groups of a few to a few dozen, while summer gatherings can number hundreds in favored coastal bays.

Seasonal migrations move narwhals from offshore, ice-edge wintering grounds into protected fjords and estuaries for summer calving and feeding. Tagging and Inuit knowledge show many populations return to the same fjords year after year.

Predictable movements matter: they guide subsistence hunting schedules, enable focused scientific monitoring, and create opportunities to protect key habitat during critical life stages.

Human interactions and conservation

Narwhals are tightly linked to human cultures, especially Inuit communities that rely on them for food, materials and seasonal knowledge. Conservation involves local stewardship, national agencies and international bodies working together.

8. Population size and conservation status: limited populations with regional differences

Global population estimates are on the order of a few hundred thousand; a commonly cited figure is roughly 170,000 individuals worldwide, though regional abundances vary and estimates carry uncertainty.

The IUCN currently lists narwhals as Near Threatened, reflecting region-specific pressures and the species’ vulnerability due to slow reproduction and site fidelity. Some aggregations—like West Greenland and parts of Canada—are closely monitored through combined scientific and Indigenous programs.

Because narwhals return to the same fjords and have low reproductive rates, local declines can be slow to reverse, so regional management and reliable monitoring are essential (IUCN, WWF and national agencies provide ongoing assessments).

9. Threats: climate change, industrial activity and hunting pressures

Key threats include loss of sea ice from climate warming, increased ship traffic and noise, oil and gas exploration, and subsistence hunting. Each pressure affects narwhals differently depending on location and timing.

Summer Arctic sea-ice minimums have declined substantially since satellite records began in 1979—by roughly 40% in September extent—which alters habitat and can shift prey deeper or poleward. Changes in prey distribution force narwhals to expend more energy or alter long-established routes.

Industrial noise and shipping can interfere with echolocation and cause displacement from feeding areas. Regulated subsistence hunts remain an important local practice; across Greenland and Canadian waters, catches typically number in the hundreds to a few thousand animals annually, managed regionally to balance cultural needs and population health.

Local co-management arrangements that integrate Indigenous knowledge with science have proved effective in many areas for setting quotas, timing hunts and identifying sensitive habitats.

10. Cultural importance and research value: Indigenous knowledge and scientific insights

Narwhals are central to Inuit life—for food, tools (including historically important tusks) and seasonal calendars that guide travel and hunting. Community knowledge about migration timing and fjord fidelity complements scientific data.

Collaborative programs combine tagging, acoustics and genetics with local monitoring—community-led aerial counts and shore-based observations are common. Museum tusk records have also been used in historical analyses of trade and distribution.

Together, Indigenous stewardship and international science provide the best path to informed management and long-term conservation of narwhals and the Arctic systems they help reveal.

Summary

- The tusk is unique—an elongated canine with sensory capacity and social roles, and a reason narwhals entered European lore.

- Narwhals are deep-diving, ice-adapted predators (dives commonly >800 m) that link surface and deep food webs and rely on thick blubber for insulation and energy.

- Populations are regionally variable (global estimates on the order of ~170,000) and vulnerable to sea-ice loss, noise and industrial activity; sustainable, locally led management matters.

- Indigenous knowledge and scientific research—tagging, acoustics and genetics—are both essential to understanding narwhal ecology and guiding conservation.

Learn more by reading IUCN and NOAA summaries, supporting reputable Arctic research groups, and exploring Indigenous perspectives on narwhal stewardship.

Behavioral observations add other functions: tusks appear in social signaling, and males sometimes use them in low-intensity sparring. A minority of females have small tusks or both canines fused, showing some variation in expression across the species.

Historically, demand for “unicorn horns” shaped European perceptions of narwhals and fed an ivory trade that still echoes in cultural records.

2. Body shape, skin and coloration: countershading and seasonal mottling

Narwhals have a slender, elongated body with a small dorsal ridge rather than a prominent fin, and a mottled gray pattern that changes with age.

Juveniles are generally darker and adults develop the patchy, blotched look—older animals can appear almost white in places. Like other marine mammals, they show countershading: darker backs and lighter bellies to reduce visibility from above and below.

Adults typically measure about 3–5 meters long, making them smaller than some baleen whales but similar in length to belugas, which tend to be uniformly white at maturity. The mottled pattern helps narwhals blend into icy, broken-light conditions when hunting beneath ice.

3. Thick blubber and cold adaptation: life in frigid waters

Narwhals rely on a substantial blubber layer for insulation in near-freezing water; that fat layer is their primary thermal barrier and an energy reserve through lean periods.

Blubber also buffers energy during migrations and seasonal fasting, and contributes to the buoyancy and streamlined shape that help with long, deep dives. Researchers note that blubber thickness correlates with body condition and survival through winters when prey can be scarce.

As sea ice patterns shift and prey distribution changes, changes in feeding opportunities can directly affect blubber stores and overall energy budgets for narwhal populations.

4. Size, growth and lifespan: medium-sized Arctic whale with multi-decade lifespan

Adult narwhals usually measure about 3–5 meters long, with males often a bit larger than females. Individuals can live for several decades—commonly up to around 50 years.

Reproduction is slow: gestation lasts roughly 14 months and females typically give birth to a single calf. Calves are sizeable at birth and are nursed and protected in coastal summer areas.

Slow reproduction and long lifespans mean populations recover slowly from elevated mortality, which is one reason careful monitoring and management are necessary.

Behavior and ecology

Narwhals are deep-diving, social toothed whales that feed in ice-associated waters and link surface and deep-sea food webs. They act as a mesopredator—connecting benthic and midwater prey to larger predators and people.

5. Deep diving and feeding: accessing prey on the continental slope

Narwhals are among the deepest-diving Arctic cetaceans. Tagging studies show routine dives well beyond 800 meters, with records approaching 1,500 meters, and dive durations commonly up to 20–25 minutes.

Their diet includes Greenland halibut, Arctic cod and squid, so foraging connects them to both benthic (sea-floor) and midwater food webs. Narwhals often target continental slopes and submarine canyons where prey aggregates.

Acoustic and tag studies reveal repeated deep-forage patterns: day-to-day trips to the same slope features. That specialization makes narwhals sensitive to shifts in prey depth or location caused by warming waters and changing oceanographic conditions.

6. Echolocation and sensory abilities: navigating under ice

Narwhals use echolocation clicks, whistles and pulsed calls to navigate, find prey and communicate beneath ice where light is limited. Echolocation lets them detect prey and cracks in the ice to reach air.

Acoustic monitoring has documented dozens of distinct call types and broadband clicks adapted to complex, ice-covered habitats (see NOAA and IWC acoustic studies). The tusk’s sensory capacity likely complements sonar by providing direct, close-range information about water chemistry and local vibrations.

Sound is central to narwhal survival: noise from ships or industry can mask echolocation signals and displace animals from important feeding or breathing sites.

7. Social structure and migration: pods, seasonal movements and ice fidelity

Narwhals form variable pods—small groups in winter and larger aggregations in summer fjords. Hunters and scientists report typical winter groups of a few to a few dozen, while summer gatherings can number hundreds in favored coastal bays.

Seasonal migrations move narwhals from offshore, ice-edge wintering grounds into protected fjords and estuaries for summer calving and feeding. Tagging and Inuit knowledge show many populations return to the same fjords year after year.

Predictable movements matter: they guide subsistence hunting schedules, enable focused scientific monitoring, and create opportunities to protect key habitat during critical life stages.

Human interactions and conservation

Narwhals are tightly linked to human cultures, especially Inuit communities that rely on them for food, materials and seasonal knowledge. Conservation involves local stewardship, national agencies and international bodies working together.

8. Population size and conservation status: limited populations with regional differences

Global population estimates are on the order of a few hundred thousand; a commonly cited figure is roughly 170,000 individuals worldwide, though regional abundances vary and estimates carry uncertainty.

The IUCN currently lists narwhals as Near Threatened, reflecting region-specific pressures and the species’ vulnerability due to slow reproduction and site fidelity. Some aggregations—like West Greenland and parts of Canada—are closely monitored through combined scientific and Indigenous programs.

Because narwhals return to the same fjords and have low reproductive rates, local declines can be slow to reverse, so regional management and reliable monitoring are essential (IUCN, WWF and national agencies provide ongoing assessments).

9. Threats: climate change, industrial activity and hunting pressures

Key threats include loss of sea ice from climate warming, increased ship traffic and noise, oil and gas exploration, and subsistence hunting. Each pressure affects narwhals differently depending on location and timing.

Summer Arctic sea-ice minimums have declined substantially since satellite records began in 1979—by roughly 40% in September extent—which alters habitat and can shift prey deeper or poleward. Changes in prey distribution force narwhals to expend more energy or alter long-established routes.

Industrial noise and shipping can interfere with echolocation and cause displacement from feeding areas. Regulated subsistence hunts remain an important local practice; across Greenland and Canadian waters, catches typically number in the hundreds to a few thousand animals annually, managed regionally to balance cultural needs and population health.

Local co-management arrangements that integrate Indigenous knowledge with science have proved effective in many areas for setting quotas, timing hunts and identifying sensitive habitats.

10. Cultural importance and research value: Indigenous knowledge and scientific insights

Narwhals are central to Inuit life—for food, tools (including historically important tusks) and seasonal calendars that guide travel and hunting. Community knowledge about migration timing and fjord fidelity complements scientific data.

Collaborative programs combine tagging, acoustics and genetics with local monitoring—community-led aerial counts and shore-based observations are common. Museum tusk records have also been used in historical analyses of trade and distribution.

Together, Indigenous stewardship and international science provide the best path to informed management and long-term conservation of narwhals and the Arctic systems they help reveal.

Summary

- The tusk is unique—an elongated canine with sensory capacity and social roles, and a reason narwhals entered European lore.

- Narwhals are deep-diving, ice-adapted predators (dives commonly >800 m) that link surface and deep food webs and rely on thick blubber for insulation and energy.

- Populations are regionally variable (global estimates on the order of ~170,000) and vulnerable to sea-ice loss, noise and industrial activity; sustainable, locally led management matters.

- Indigenous knowledge and scientific research—tagging, acoustics and genetics—are both essential to understanding narwhal ecology and guiding conservation.

Learn more by reading IUCN and NOAA summaries, supporting reputable Arctic research groups, and exploring Indigenous perspectives on narwhal stewardship.

For centuries, Arctic hunters brought narwhal tusks to European markets and called them “unicorn horns”—a prized curiosity that blurred myth and natural history.

Those tusks and the animals that carry them matter beyond legend. Narwhals are a window into how Arctic ecosystems function and why rapid changes in sea ice affect people and wildlife alike.

This article breaks down 10 defining characteristics of a narwhal—Monodon monoceros—mixing biology, behavior, and human connections to explain what makes this Arctic whale unique. Expect three groups of traits: physical features, life-history and ecology, and human interactions plus conservation. Narwhals live in Arctic waters around Greenland, Canada and Russia, often close to sea ice and deep continental slopes.

Physical characteristics

These features—tusk, body shape, thick blubber and overall size—were shaped by life in near-freezing waters. Each trait helps narwhals hunt under ice, store energy and survive long dives.

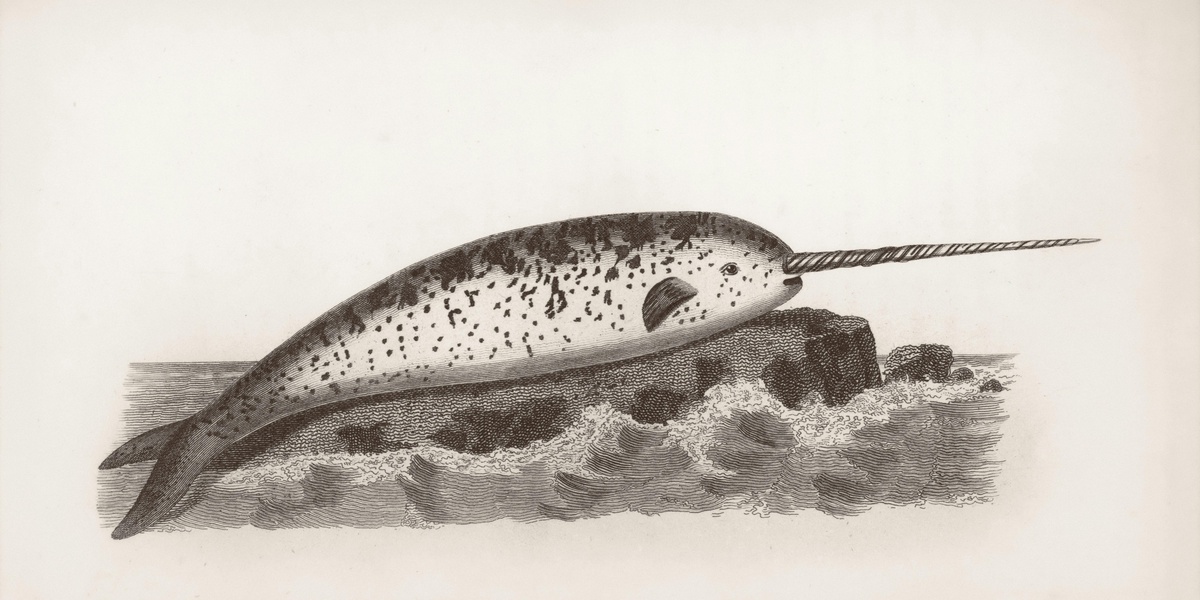

1. Tusk: an elongated canine tooth used as a sensory organ

The classic narwhal tusk is an elongated upper left canine tooth, most commonly seen in males. It projects forward in a left-handed spiral and can reach about 3 meters (9.8 feet) in museum specimens.

Research shows the tusk isn’t just for show: its core contains millions of nerve endings that detect temperature, salinity and subtle vibrations in the water, giving males a large, sensitive probe for the environment (see IUCN and peer-reviewed sensory studies).

Behavioral observations add other functions: tusks appear in social signaling, and males sometimes use them in low-intensity sparring. A minority of females have small tusks or both canines fused, showing some variation in expression across the species.

Historically, demand for “unicorn horns” shaped European perceptions of narwhals and fed an ivory trade that still echoes in cultural records.

2. Body shape, skin and coloration: countershading and seasonal mottling

Narwhals have a slender, elongated body with a small dorsal ridge rather than a prominent fin, and a mottled gray pattern that changes with age.

Juveniles are generally darker and adults develop the patchy, blotched look—older animals can appear almost white in places. Like other marine mammals, they show countershading: darker backs and lighter bellies to reduce visibility from above and below.

Adults typically measure about 3–5 meters long, making them smaller than some baleen whales but similar in length to belugas, which tend to be uniformly white at maturity. The mottled pattern helps narwhals blend into icy, broken-light conditions when hunting beneath ice.

3. Thick blubber and cold adaptation: life in frigid waters

Narwhals rely on a substantial blubber layer for insulation in near-freezing water; that fat layer is their primary thermal barrier and an energy reserve through lean periods.

Blubber also buffers energy during migrations and seasonal fasting, and contributes to the buoyancy and streamlined shape that help with long, deep dives. Researchers note that blubber thickness correlates with body condition and survival through winters when prey can be scarce.

As sea ice patterns shift and prey distribution changes, changes in feeding opportunities can directly affect blubber stores and overall energy budgets for narwhal populations.

4. Size, growth and lifespan: medium-sized Arctic whale with multi-decade lifespan

Adult narwhals usually measure about 3–5 meters long, with males often a bit larger than females. Individuals can live for several decades—commonly up to around 50 years.

Reproduction is slow: gestation lasts roughly 14 months and females typically give birth to a single calf. Calves are sizeable at birth and are nursed and protected in coastal summer areas.

Slow reproduction and long lifespans mean populations recover slowly from elevated mortality, which is one reason careful monitoring and management are necessary.

Behavior and ecology

Narwhals are deep-diving, social toothed whales that feed in ice-associated waters and link surface and deep-sea food webs. They act as a mesopredator—connecting benthic and midwater prey to larger predators and people.

5. Deep diving and feeding: accessing prey on the continental slope

Narwhals are among the deepest-diving Arctic cetaceans. Tagging studies show routine dives well beyond 800 meters, with records approaching 1,500 meters, and dive durations commonly up to 20–25 minutes.

Their diet includes Greenland halibut, Arctic cod and squid, so foraging connects them to both benthic (sea-floor) and midwater food webs. Narwhals often target continental slopes and submarine canyons where prey aggregates.

Acoustic and tag studies reveal repeated deep-forage patterns: day-to-day trips to the same slope features. That specialization makes narwhals sensitive to shifts in prey depth or location caused by warming waters and changing oceanographic conditions.

6. Echolocation and sensory abilities: navigating under ice

Narwhals use echolocation clicks, whistles and pulsed calls to navigate, find prey and communicate beneath ice where light is limited. Echolocation lets them detect prey and cracks in the ice to reach air.

Acoustic monitoring has documented dozens of distinct call types and broadband clicks adapted to complex, ice-covered habitats (see NOAA and IWC acoustic studies). The tusk’s sensory capacity likely complements sonar by providing direct, close-range information about water chemistry and local vibrations.

Sound is central to narwhal survival: noise from ships or industry can mask echolocation signals and displace animals from important feeding or breathing sites.

7. Social structure and migration: pods, seasonal movements and ice fidelity

Narwhals form variable pods—small groups in winter and larger aggregations in summer fjords. Hunters and scientists report typical winter groups of a few to a few dozen, while summer gatherings can number hundreds in favored coastal bays.

Seasonal migrations move narwhals from offshore, ice-edge wintering grounds into protected fjords and estuaries for summer calving and feeding. Tagging and Inuit knowledge show many populations return to the same fjords year after year.

Predictable movements matter: they guide subsistence hunting schedules, enable focused scientific monitoring, and create opportunities to protect key habitat during critical life stages.

Human interactions and conservation

Narwhals are tightly linked to human cultures, especially Inuit communities that rely on them for food, materials and seasonal knowledge. Conservation involves local stewardship, national agencies and international bodies working together.

8. Population size and conservation status: limited populations with regional differences

Global population estimates are on the order of a few hundred thousand; a commonly cited figure is roughly 170,000 individuals worldwide, though regional abundances vary and estimates carry uncertainty.

The IUCN currently lists narwhals as Near Threatened, reflecting region-specific pressures and the species’ vulnerability due to slow reproduction and site fidelity. Some aggregations—like West Greenland and parts of Canada—are closely monitored through combined scientific and Indigenous programs.

Because narwhals return to the same fjords and have low reproductive rates, local declines can be slow to reverse, so regional management and reliable monitoring are essential (IUCN, WWF and national agencies provide ongoing assessments).

9. Threats: climate change, industrial activity and hunting pressures

Key threats include loss of sea ice from climate warming, increased ship traffic and noise, oil and gas exploration, and subsistence hunting. Each pressure affects narwhals differently depending on location and timing.

Summer Arctic sea-ice minimums have declined substantially since satellite records began in 1979—by roughly 40% in September extent—which alters habitat and can shift prey deeper or poleward. Changes in prey distribution force narwhals to expend more energy or alter long-established routes.

Industrial noise and shipping can interfere with echolocation and cause displacement from feeding areas. Regulated subsistence hunts remain an important local practice; across Greenland and Canadian waters, catches typically number in the hundreds to a few thousand animals annually, managed regionally to balance cultural needs and population health.

Local co-management arrangements that integrate Indigenous knowledge with science have proved effective in many areas for setting quotas, timing hunts and identifying sensitive habitats.

10. Cultural importance and research value: Indigenous knowledge and scientific insights

Narwhals are central to Inuit life—for food, tools (including historically important tusks) and seasonal calendars that guide travel and hunting. Community knowledge about migration timing and fjord fidelity complements scientific data.

Collaborative programs combine tagging, acoustics and genetics with local monitoring—community-led aerial counts and shore-based observations are common. Museum tusk records have also been used in historical analyses of trade and distribution.

Together, Indigenous stewardship and international science provide the best path to informed management and long-term conservation of narwhals and the Arctic systems they help reveal.

Summary

- The tusk is unique—an elongated canine with sensory capacity and social roles, and a reason narwhals entered European lore.

- Narwhals are deep-diving, ice-adapted predators (dives commonly >800 m) that link surface and deep food webs and rely on thick blubber for insulation and energy.

- Populations are regionally variable (global estimates on the order of ~170,000) and vulnerable to sea-ice loss, noise and industrial activity; sustainable, locally led management matters.

- Indigenous knowledge and scientific research—tagging, acoustics and genetics—are both essential to understanding narwhal ecology and guiding conservation.

Learn more by reading IUCN and NOAA summaries, supporting reputable Arctic research groups, and exploring Indigenous perspectives on narwhal stewardship.