Roughly one in three bites of food worldwide depends on animal pollinators — a single statistic that links backyard flowers to global food security.

Naturalists from the 18th and 19th centuries noticed insects visiting blossoms and wrote the first careful observations tying those visits to seed set and fruiting. Over the next two centuries scientists learned that many plants and animals have coevolved traits that fit together like lock and key.

Plant–pollinator interactions are foundational to ecosystems, agriculture, culture, and human health; understanding eight key facts about these relationships reveals why they deserve urgent attention. Below are eight evidence-based facts about plant–pollinator interactions covering ecological roles, economic effects, cultural links, and conservation responses. The phrase “facts about plant pollinator interactions” appears sparingly in this piece, and the rest of the text uses natural variations such as “plant–pollinator relationships” and “pollination services.”

Ecological Foundations of Plant–Pollinator Interactions

1. Pollination is the gateway to plant reproduction

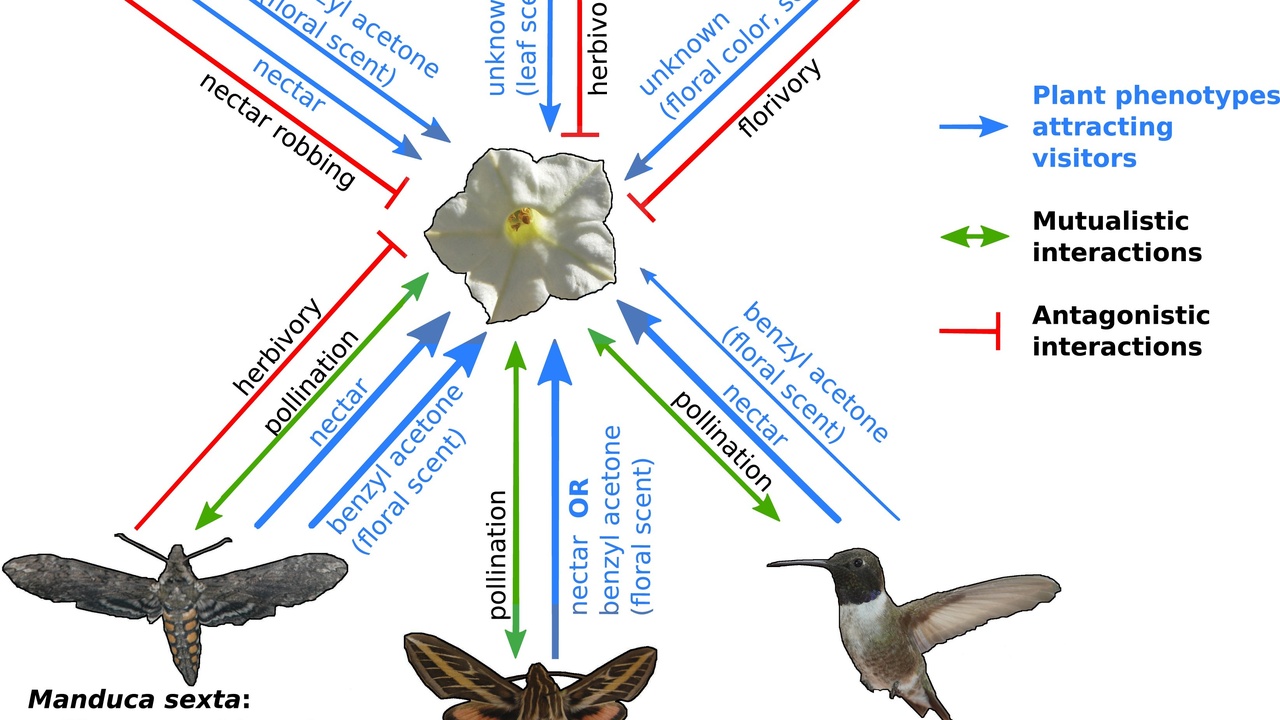

Pollination moves pollen from the male parts of a flower to the female parts, enabling fertilization and the production of seeds and fruit. Many flowering plants rely on animals to carry pollen between flowers, attracted by nectar, pollen, scent, or showy petals.

This transfer underpins seed and fruit production across wild ecosystems and farms; apples, almonds, and coffee are clear examples where animal visitors substantially increase yield and quality. Almond orchards in California, for instance, rent thousands of honeybee hives each spring to secure pollination for nut set.

That reproductive role links directly to biodiversity: fewer successful pollination events mean fewer seeds and weaker plant recruitment, which alters community composition over time.

2. Pollinators sustain biodiversity and plant communities

Animal pollinators maintain plant diversity by enabling sexual reproduction and gene flow across landscapes. Some plants are generalized, visited by many insects, while others have highly specialized relationships that drive coevolution and sometimes speciation.

Examples include fig trees (Ficus) that depend on specific fig wasps, and many orchids that rely on a single pollinator species to reproduce. Those tight pairings can create unique ecological niches and help shape entire plant communities.

When pollination networks remain intact they support fruit-bearing plants that feed birds and mammals, linking pollination directly to broader food webs and ecosystem function.

3. Pollinator networks boost ecosystem resilience

Diverse pollinator communities increase resilience because redundancy and complementarity mean several species can service the same plant. If one pollinator declines, others can maintain reproductive function for many plants.

Research shows that ecosystems with multiple pollinator functional groups—solitary bees, bumblebees, butterflies, hoverflies, and birds—tend to buffer plant reproduction against weather variability and local species losses.

Practical restoration work—such as planting native wildflower strips or hedgerows—strengthens network diversity and helps stabilize pollination services across disturbed agricultural landscapes.

Economic and Agricultural Impacts

Among the key facts about plant pollinator interactions is how directly those relationships translate into farm income and food availability. Pollination services affect yield, fruit quality, and the economic viability of many specialty and staple crops.

4. Many staple and specialty crops rely on animal pollination

A substantial share of global crops—fruits, nuts, some vegetables, and many stimulants like coffee and cocoa—benefit from animal visits. Estimates commonly cited suggest roughly three-quarters of leading global food crops receive some benefit from animal pollination, though dependence varies by crop and region.

Some crops are highly dependent: almonds, apples, blueberries, vanilla, and many tree fruits need animal pollination for commercial yields. Others show partial dependence—crops such as tomatoes and cucurbits may set fruit without animals but produce higher yields or better-shaped produce when pollinators visit.

Loss of pollinators would not only reduce yields but also narrow dietary diversity, since many nutrient-rich foods—berries, nuts, and a range of vegetables—rely on animal-assisted pollination.

5. Pollination services have large economic value

Valuation studies often place the global economic value of animal pollination in the low hundreds of billions of US dollars per year, though methods and estimates vary. Those figures reflect added yield, improved quality, and market premiums for well-formed fruits and nuts.

On farms this value appears as higher income for producers and lower volatility in supply. For example, almond growers pay rental fees for honeybee hives in the spring, and coffee producers in some regions report measurable yield increases when bee diversity is high.

When pollination fails, farmers may face reduced harvests, higher per-unit costs, and consumers may see price spikes for pollinator-dependent commodities during poor pollination years.

6. Farming practices and landscape design shape pollination outcomes

Agricultural management and the surrounding landscape largely determine whether pollinators thrive. Monocultures and large-scale pesticide use reduce floral and nesting resources, while diversified farms and habitat patches support richer pollinator communities.

Practical measures that increase pollination include planting hedgerows, establishing wildflower strips, rotating crops, and adopting integrated pest management to cut unnecessary insecticide use. European agri-environment schemes and pilot projects in Latin America show yield and biodiversity gains where such practices are applied.

Those landscape-level changes pay off by increasing pollinator visitation rates and stabilizing production across seasons.

Human Health, Culture and Conservation

Pollination links directly to human nutrition, traditional medicine, and cultural identity in many places. At the same time, pollinators face multiple threats that require action at household, farm, and policy levels.

7. Pollinators support nutrition, medicine, and cultural practices

Many micronutrient-rich foods—fruit, nuts, and certain vegetables—depend on animal pollinators, so healthy pollination supports dietary diversity and human health. Smallholder farmers often rely on those crops for both food and income.

Traditional medicines and cultural foods also trace back to pollinated plants: native berries, herbs, and tree fruits used in remedies and ceremonies depend on insect or bird pollination in numerous regions. Harvest festivals and local markets celebrate those seasonal relationships.

Community-based projects that revive native pollinator plants can therefore bolster nutrition, cultural continuity, and livelihoods at once.

8. Threats to pollinators and how people can help

Main threats include habitat loss from land conversion, pesticide exposure (neonicotinoids are a widely discussed example), parasites and diseases such as the Varroa mite in honeybees, and the shifting timing and ranges caused by climate change. These pressures often interact and compound one another.

Policy and landscape responses range from pesticide regulation and protected-area expansion to incentives for pollinator-friendly farming. Citizen science programs—bee monitoring and floral surveys—provide valuable data and engage communities in conservation.

Practical actions individuals and farmers can take include planting native wildflowers that bloom across the growing season, leaving small bare-soil patches for ground-nesting bees, avoiding sprays during bloom, installing simple bee hotels where appropriate, and supporting integrated pest management on farms.

Collective action—voting for policies that protect habitats, backing research, and joining local restoration events—helps scale those local steps into meaningful landscape change.

Summary

- Pollination underpins both wild plant reproduction and many crops; diverse pollinators keep ecosystems productive and resilient.

- Animal pollination supports nutrition and livelihoods, with substantial economic value—protecting pollinators helps secure food quality and farmer income.

- Simple actions—plant native flowers, reduce pesticide use, support habitat on farms and in towns, and join monitoring or policy efforts—make a measurable difference for pollinators.