In the 1980s researchers attached the first satellite tags to whales and discovered migrations that spanned entire ocean basins — journeys that redefined how we think about marine life. Those early tags showed not only distance but fidelity: animals returning to the same hotspots year after year. Migration matters because it links distant ecosystems, supports fisheries and coastal ecotourism, and signals changing ocean conditions that affect people. Humpback whales, for example, regularly travel thousands of kilometers between feeding and breeding areas — some populations move up to ~8,000 km one way — and those movements ripple through food webs and economies. Understanding seven essential facts about marine mammal migration explains what drives these trips, how animals navigate, the physiological and social tools they use, the services migrants provide to oceans, the human threats they encounter, and the conservation tools that can protect migration routes.

How and why marine mammals migrate

Seasonal movements in marine mammals are driven mainly by the need to balance feeding and reproduction while managing temperature and safety for young. In high-latitude seas, summer productivity creates dense feeding opportunities, so many species spend months at rich polar or temperate feeding grounds and then move to warmer, lower‑latitude waters to breed and nurse calves. Those shifts involve energetic trade-offs: long travel consumes energy but offers safer, calmer waters for birthing and reduced predator risk. Timing is crucial — animals match departures and returns to plankton blooms or fish migrations. The pattern applies from baleen whales and toothed whales to seals and sea lions, though distances and strategies vary widely. Knowing these movement patterns helps managers predict where animals will be when fisheries or shipping overlap with key life stages.

1. Seasonal drivers and astonishing distances

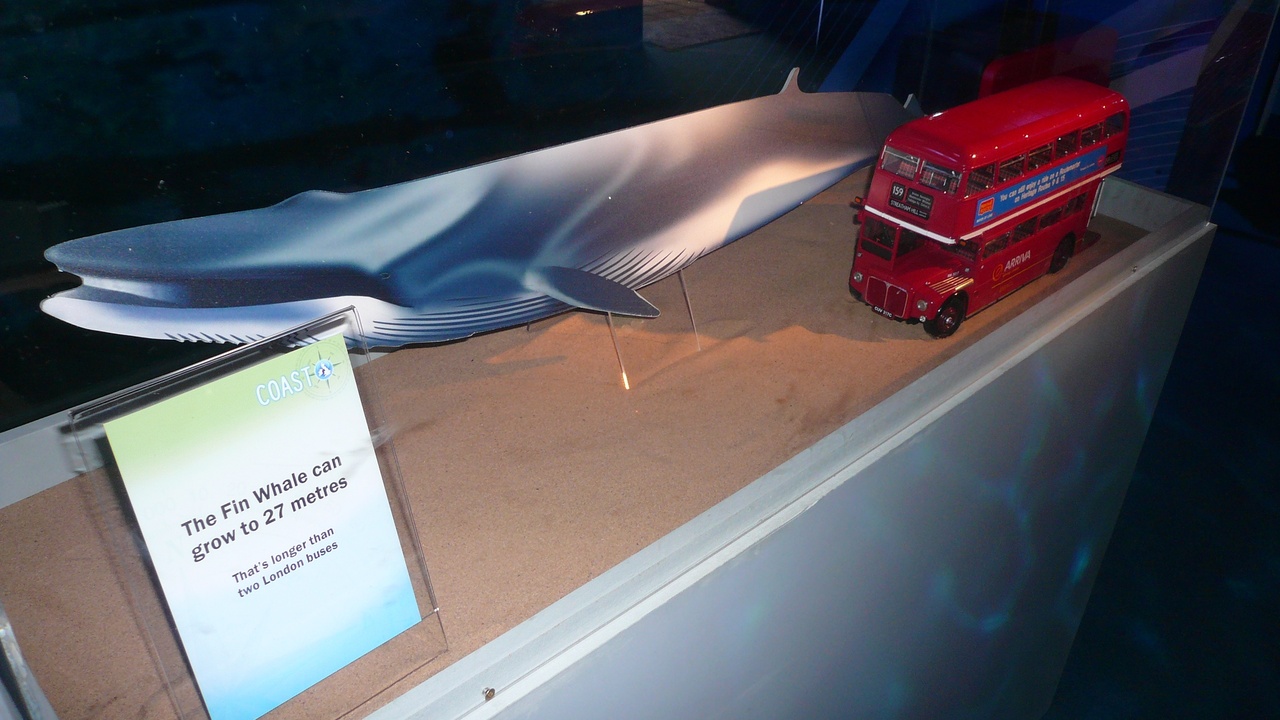

Many marine mammals travel thousands of kilometers between feeding and breeding areas. Humpback whales are among the longest-distance travelers, with some populations recorded moving up to ~8,000 km one way. Gray whales make famous north–south journeys along the eastern Pacific, covering roughly 16,000 km round trip for some individuals. Pinnipeds, such as seals, often commute seasonally between productive offshore feeding zones and coastal haul-outs used for breeding and molting.

Feeding migrations generally target seasonal productivity — polar summers bring plankton and fish to the surface — while breeding migrations favor warmer, shallower waters where calves have higher survival odds. Those long links connect remote ecosystems, so a whale feeding in Arctic waters can influence coastal productivity thousands of kilometers away, with knock-on effects for fisheries and wildlife tourism.

2. How animals navigate oceans

Marine mammals rely on multiple cues to navigate long routes: the Earth’s magnetic field, the sun and stars, ocean currents, and acoustic landmarks like familiar choruses or bathymetric features. Tagging and tracking programs (satellite tags and Argos telemetry first widely used in the 1980s and 1990s) revealed surprisingly straight, repeatable routes, implying reliable internal or learned maps.

Evidence for magnetoreception comes from experiments and correlations between movement and magnetic anomalies, while acoustic studies show animals use soundscapes — whale calls, ice noise, and seafloor echoes — as bearings in low-visibility seas. Social cues also matter: younger animals often follow experienced leaders, so group knowledge helps maintain corridors. Mapping these navigation cues is practical: it lets researchers identify critical corridors for mitigation and design protected zones that align with the animals’ own guidance systems.

3. Physiological adaptations that make long journeys possible

Blubber, fasting strategies, and specialized dive physiology enable long migrations. Thick blubber provides insulation and an energy reserve when animals reduce feeding during breeding seasons. Some pinnipeds and baleen whales fast or eat very little while nursing, relying on stored energy to sustain lactation and travel.

Diving adaptations include efficient oxygen storage and slow heart rates; sperm whales routinely dive deeper than 1,000 m to reach prey, a capability that also influences where they feed during migrations. Female seals and elephant seals can fast for several weeks to over a month while nursing, concentrating energy use on offspring. Understanding those energy budgets helps predict how animals will respond if prey patterns shift due to climate change or human impacts.

Behavior, culture, and ecosystem roles

Migration is more than movement; it’s woven into social lives and ecosystem function. Routes and timing can be culturally transmitted, songs and hunting techniques spread through populations, and the presence of migrating mammals alters nutrient flows and predator–prey dynamics. Migrants transport nutrients vertically and horizontally — the so‑called “whale pump” — and their seasonal arrival or absence can change the timing and intensity of local productivity. These behaviors mean that shifts in migration timing or population structure can ripple through food webs and human economies alike.

4. Migration routes can be cultural — not just instinctual

Many marine mammals learn routes and behaviors from elders rather than relying solely on instinct. Long-term tracking shows populations repeatedly use the same corridors over decades, and behavioral studies document transmission of songs, hunting tactics, and range knowledge across generations. Orca pods display strong matrilineal traditions in range and prey choice, while humpback song patterns can spread across ocean basins.

That cultural aspect has consequences: removing experienced individuals through strandings, hunting, or chronic mortality can erode a population’s navigational memory. When route knowledge disappears, recolonization of former habitats can be slow or fail, making cultural preservation — not just population counts — important for conservation.

5. Migrants shape ecosystems — from polar seas to coastal bays

Migrating mammals move nutrients and energy across ocean zones. When whales feed at depth and defecate near the surface, they bring nitrogen and iron into sunlit waters, stimulating phytoplankton growth that supports the entire food web. Seals and sea lions concentrate nutrients near haul-outs and breeding beaches, affecting nearshore productivity.

The timing of migrations matters: predators arriving with seasonal prey can amplify or dampen local fisheries, and large migrations may influence carbon cycling by shifting where biological productivity occurs. For coastal communities, those effects translate into changing catch rates and opportunities for wildlife viewing that support tourism.

Human impacts and conservation responses

Migration corridors intersect with human activities — shipping lanes, fishing grounds, and coastal development — creating collision, entanglement, and noise risks. Climate change is shifting prey and altering timing, forcing animals to adjust routes. Conservation responses use tools like marine protected areas, seasonal vessel speed restrictions, satellite tagging, and passive acoustic monitoring to reduce risk and track changes. Organizations such as NOAA, the International Whaling Commission (IWC), and regional groups deploy tagging and acoustic arrays to inform policy and design protective measures. These efforts form the backbone of contemporary strategies to keep migrants moving safely.

6. Migration corridors expose animals to human risks

Migration paths frequently overlap busy commercial routes and productive fishing areas, increasing the chance of ship strikes, entanglement in gear, and harmful noise. The North Atlantic right whale illustrates the danger: fewer than 400 individuals remain, and many deaths trace to vessel collisions and rope entanglements. Such losses carry ecological and economic costs, from reduced whale-watching income to strained fisheries when management measures are imposed.

Beyond direct mortality, chronic disturbances — elevated noise levels or repeated nearshore displacement — can reduce feeding efficiency and calf survival, leading to long-term population declines. Managers must weigh both immediate threats and subtle, long-term impacts when protecting corridors.

7. Monitoring and protection are getting smarter — but challenges remain

Modern tools are improving protections. Satellite tags, passive acoustic monitoring (PAM) arrays, and predictive habitat models help map corridors and forecast presence. NOAA tagging programs and international research teams use these data to inform seasonal advisories and dynamic management. Seasonal speed limits (often around 10 knots) and re-routing have produced measurable reductions in strike risk in several regions.

Still, gaps remain: coverage is patchy, enforcement and funding are inconsistent, and climate-driven shifts can outpace static protected areas. Emerging tech — near-real-time tracking, AI-driven acoustic detection, and vessel-alert systems based on predictive models — offers promise for more responsive protections. Combining policy tools (MPAs, seasonal restrictions, gear modifications) with improved monitoring gives the best chance to keep migrants safe as oceans change.

Summary

- Migrations link distant ecosystems and economies: many species travel thousands of kilometers (humpbacks up to ~8,000 km one way), connecting polar feeding grounds with low‑latitude breeding areas.

- Routes are guided by multiple cues and often taught socially: navigation uses magnetic, celestial, current, and acoustic landmarks, and cultural transmission (for example in orca pods and humpback song spread) preserves route knowledge.

- Migrants deliver ecosystem services: whales and seals redistribute nutrients (the “whale pump”), influencing productivity, carbon cycling, and fisheries at regional scales.

- Human threats concentrate along corridors, but improved monitoring and policies — from satellite tagging and PAM arrays to seasonal 10‑knot speed limits and protected corridors promoted by NOAA and the IWC — can reduce risks; continued investment and adaptive management are needed.