In 1976 The Land Institute was founded with a bold idea: breed perennial grains to mimic prairie ecosystems and reduce the environmental toll of annual cropping.

That idea matters now more than ever. Food security, soil health, climate resilience, and farm profitability are all under pressure. Farmers, researchers, and policymakers are testing long-lived crops and mixed perennial systems to address those challenges.

Perennial agriculture offers a suite of ecological, economic, and resilience benefits that make it a powerful complement to—and in some cases an alternative to—today’s annual‑based farming systems.

Below are 10 specific advantages grouped into four practical categories: soil & environment, water & climate resilience, farm economics & productivity, and biodiversity & ecosystem services. Expect numbers, examples (Kernza®, prairie strips, switchgrass), and actionable takeaways.

Environmental and Soil-Health Benefits

Perennial root systems differ from annuals in three big ways: they go deeper, they persist year-round, and they cut out repeated tillage. Deep, fibrous roots build soil structure and organic matter. Year-round cover limits erosion and keeps living roots feeding soil life. And less tillage preserves pore networks and carbon. The Land Institute (1976) and prairie restoration projects on the Great Plains show why this matters for long-term productivity.

1. Increased Soil Carbon Storage

Perennial systems tend to store more soil carbon than annual systems because roots deposit carbon deeper and soils see less disturbance. Many perennial grass systems sequester roughly 0.5–1.5 tonnes of carbon per hectare per year (t C/ha/yr), though rates vary by climate and species.

Deep roots push carbon into subsoil horizons where it persists longer. Trials with miscanthus and switchgrass (used for bioenergy) and temperate prairie restorations have demonstrated measurable gains. That creates on‑farm fertility and creates potential revenue through carbon payments or ecosystem‑service programs (USDA and peer‑reviewed studies report these ranges).

2. Reduced Soil Erosion and Improved Structure

Perennial cover protects soil year‑round and cuts erosion versus tilled annuals. Depending on slope and rainfall, perennial cover can reduce sheet and rill erosion by roughly 50–90% compared with bare, tilled fields.

Living roots and surface residue bind aggregates and keep pore networks intact. Fewer sediment loads reach streams, lowering dredging and water‑treatment costs. Prairie strips at Iowa State are a concrete example—small perennial strips in row‑crop landscapes reduced runoff and nutrient loss in field trials.

3. Improved Soil Fertility and Microbial Health

Perennials build biological fertility by supporting diverse microbial and mycorrhizal communities. Continuous root exudates feed microbes, and deeper roots mine nutrients from subsoil layers and recycle them to the surface.

Mixed perennial‑legume systems and agroforestry plots can reduce synthetic nitrogen demand substantially—reports range from 20–50% lower N needs in some systems—although results vary. Practically, that means fewer fertilizer applications, lower input costs, and steadier nutrient availability for forage and food crops.

Water Management and Climate Resilience

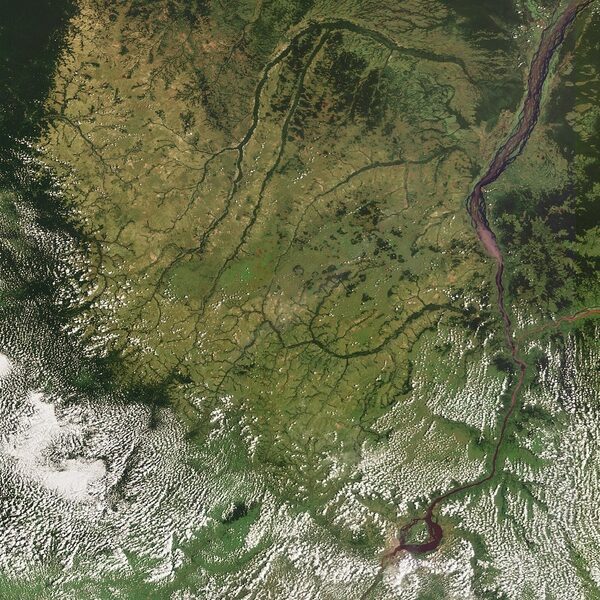

Perennial systems change how water moves through the landscape. By increasing infiltration and holding water in the soil, they reduce runoff and buffer farms from floods and droughts. Benefits depend on species selection and where plants are placed—riparian buffers, prairie strips, and deep‑rooted grasses all perform differently, but the trend is clear.

4. Enhanced Water Infiltration and Retention

Deep roots and intact pore networks increase infiltration rates. Infiltration can rise several‑fold versus compacted, tilled soils. Many perennial roots reach 1–3 meters; switchgrass roots have been documented to 2–3 m in some trials.

That stored water reduces ponding, lowers irrigation needs, and improves drought survival. Field trials with prairie strips and perennial cover crops in the Midwest showed noticeably less surface runoff after heavy storms.

5. Reduced Nutrient Runoff and Cleaner Waterways

Perennial buffers, intercropped perennials, and riparian plantings capture and cycle nutrients before they reach streams. Vegetation buffers and prairie strips have been shown to cut sediment and phosphorus runoff by roughly 30–90% depending on design and context.

Cleaner waterways mean lower drinking‑water treatment costs and healthier fisheries. Practical examples include buffer strips beside corn and soybean fields in the U.S. Midwest and riparian restoration projects that reconnect floodplains and slow nutrient transport.

6. Greater Resilience to Drought and Extreme Weather

Perennial systems often outperform annuals during drought and extreme events because roots tap deeper moisture and soils stay more stable. Multi‑year trials show some perennial pastures maintain higher forage yields in drought years than shallow‑rooted annuals.

That resilience stabilizes farm income and supplies. Silvopasture and perennial bioenergy plots are practical examples—these systems retained productive biomass through variable seasons where annuals failed.

Economic and Farm-Productivity Benefits

Perennial practices alter farm economics in three ways: they lower recurring inputs, reduce labor peaks, and open new markets. Upfront transition costs and learning curves exist, but long‑term margins can improve. Kernza® commercialization and agroforestry enterprises illustrate new revenue pathways.

7. Lower Input Costs and Reduced Labor

Fewer tillage passes and less annual replanting lower fuel, seed, and labor costs. Some farmers report fuel and labor reductions in the 20–40% range after moving to reduced‑till perennial systems, though savings vary by operation.

That change evens out labor through the year, reduces machine wear, and frees cash flow during busy planting seasons. Pasture‑based dairies and perennial forage operations often see immediate reductions in tractor hours and seed purchases.

8. Stable Yields and New Market Opportunities

Perennial crops and agroforestry can deliver steady multi‑year yields after establishment. Perennials often yield less in year one, then stabilize in years two and beyond, giving producers predictable returns across seasons.

Kernza® (intermediate wheatgrass) is a tangible example: commercial trials and partnerships with millers and bakers are building demand for perennial grain products. Other markets—bioenergy, specialty fibers, timber, nuts—plus payments for ecosystem services, diversify income and reduce seasonal risk.

Biodiversity and Ecosystem-Service Benefits

Perennial systems support above‑ and below‑ground biodiversity in ways annual monocultures rarely do. Continuous floral resources, structural habitat, and stable soils boost pollinators, beneficial insects, birds, and microbes. On a landscape scale, perennial plantings improve habitat connectivity and ecological corridors.

9. Enhanced Habitat for Pollinators and Wildlife

Perennials provide continuous nectar, pollen, and shelter, which increases pollinator abundance and diversity. Field studies of wildflower strips and hedgerows record measurable increases in pollinator visitation and local species richness.

That boosts pollination services for nearby crops and helps conservation goals. Many agri‑environment schemes and farm pollinator programs in Europe and North America promote perennial plantings for these reasons.

10. Natural Pest Regulation and Ecosystem Services

Perennial habitats often harbor predators and parasitoids that suppress pests, lowering the need for insecticide sprays. Greater landscape complexity and stable refugia let natural enemies persist between cropping seasons.

Examples include beetle banks, agroforestry borders, and hedgerows that reduce aphid and other pest outbreaks on adjacent fields. The practical outcome: fewer sprays, lower costs, and healthier on‑farm ecosystems.

Summary

Together these 10 benefits make a strong case for perennial cropping systems as tools for more resilient, profitable, and ecologically healthier farming. Soil carbon gains, water buffering, cost savings, and biodiversity improvements stack up across landscapes and enterprises.

- Perennial systems can sequester 0.5–1.5 t C/ha/yr and push roots to 1–3 m depth, locking carbon belowground.

- Perennial cover and prairie strips have cut runoff and nutrient loss by roughly 30–90% in field trials (Iowa State and others).

- Farmers report 20–40% reductions in fuel and labor on some perennial enterprises; Kernza® and silvopasture show practical market and income options.

- Perennial plantings support pollinators, natural pest enemies, and wider ecosystem services—good for yields and conservation.

Explore local trials, visit demonstration sites (Kernza, prairie strips, silvopasture), and support policies that reward long‑lived crops and ecosystem services. Practical pilots—backed by research from The Land Institute (1976) and USDA studies—are the next step for farmers and communities ready to act.