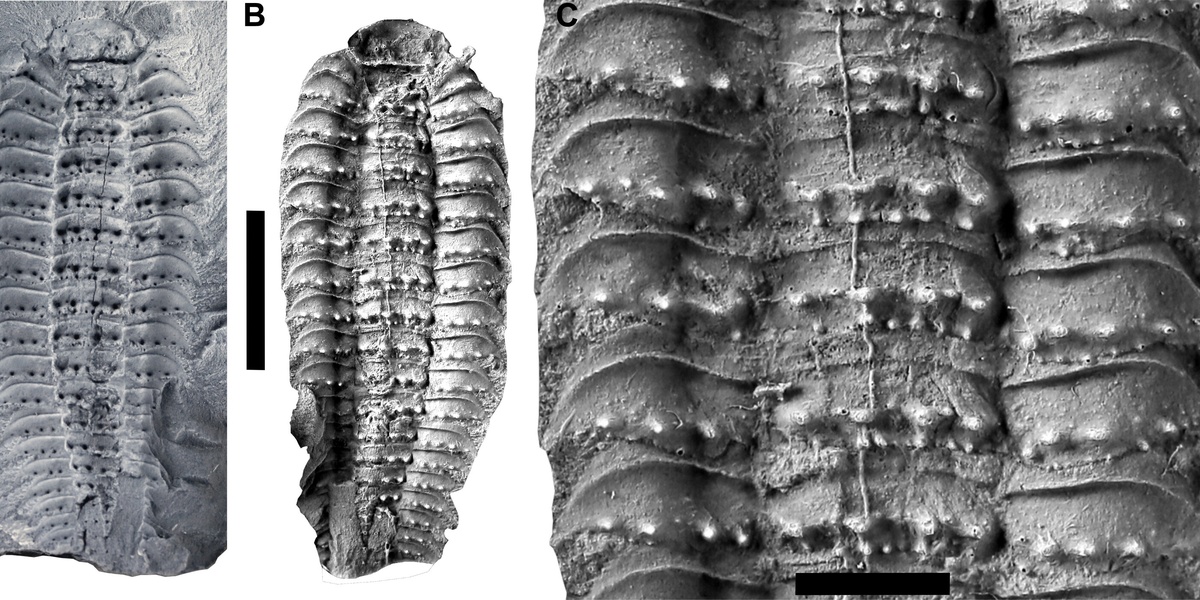

Fossil evidence shows centipede-like myriapods existed roughly 420 million years ago, making them one of the planet’s oldest terrestrial predators.

They matter because they quietly shape invertebrate communities, help control household pests, and have venoms and locomotor systems that interest scientists and engineers. There are about 3,300 described species, and that diversity explains a lot of variation in size, behaviour, and habitat.

This piece outlines 10 clear characteristics of a centipede — traits that span anatomy, behaviour, defense, and interactions with people and research.

Anatomy & Physiology

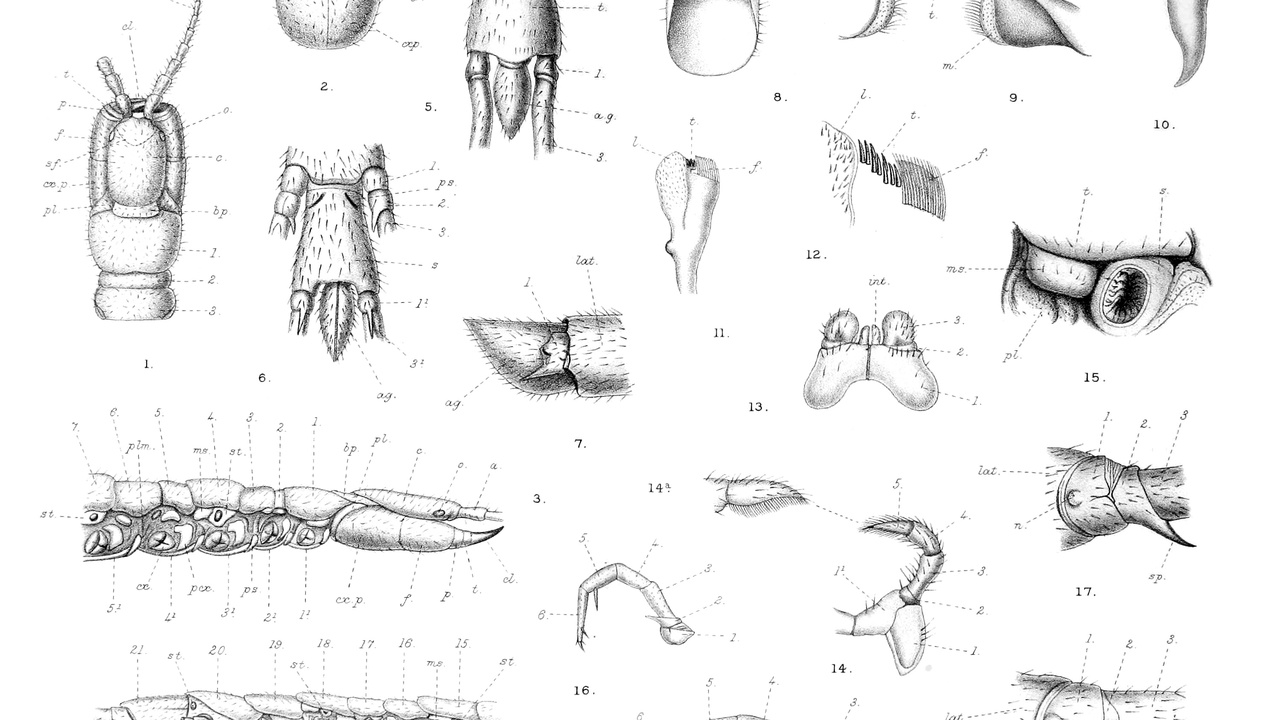

Centipedes have a distinctive body plan among arthropods: a segmented trunk with one pair of legs per segment, a head with antennae, and the first pair of appendages modified into venom-bearing structures. Their respiratory system is tracheal, and eye development varies across groups.

Leg counts and body proportions differ dramatically between species, from compact temperate forms to long, fast tropical hunters. Below are three core anatomical characteristics that explain how centipedes move and capture prey.

1. Body segmentation and leg pairs

Centipedes possess a series of body segments with one pair of legs attached to each segment — that single-pair-per-segment rule is a defining feature.

Leg-pair counts typically range from about 15 to nearly 200 pairs, yielding roughly 30 to almost 400 individual legs in extreme cases. Count varies by taxon and changes as some juveniles add segments through anamorphic development.

Species diversity (around 3,300 described species) helps explain this range: the familiar house centipede Scutigera coleoptrata has 15 pairs of legs, while large tropical Scolopendra can sport many more segments and legs.

2. Forcipules: modified front legs that deliver venom

The first pair of appendages on a centipede are not ordinary legs but forcipules — pincer-like structures that inject venom into prey. Mechanically they grasp and press a venom canal into tissue, combining a bite and envenomation in one action.

Venom composition varies between species, containing peptides and enzymes tuned to immobilize arthropod prey and, in large species, small vertebrates. Human bites typically cause sharp local pain and swelling; serious systemic reactions are uncommon and fatalities are rare.

Medical interest often focuses on large Scolopendra species such as S. subspinipes and S. gigantea, which deliver stronger envenomations and have produced hospital-treated cases in warm regions.

3. Respiratory and sensory systems adapted for life in narrow spaces

Centipedes breathe through a tracheal network rather than lungs, which suits life in soil, leaf litter, and crevices where gas exchange occurs close to the body surface.

Sensory input depends largely on antennae for tactile and chemical cues; eyes range from well-developed ocelli in surface-active species to reduced or absent eyes in cave or burrowing taxa. These adaptations support nocturnal hunting and rapid movement through cluttered substrates.

Behavior & Ecology

Centipedes are mostly nocturnal predators that influence invertebrate populations across a wide range of terrestrial habitats. They occur from tropical rainforests to temperate woodlands, though they’re absent from Antarctica and the highest alpine extremes.

Their behaviours range from active pursuit to ambush hunting, and reproductive and life-history strategies vary among groups. The next three points explore diet, distribution, and life cycle.

4. Predatory diet and hunting techniques

Centipedes feed on insects, spiders, and, in larger species, small vertebrates such as frogs, lizards, and occasionally rodents. Hunting tactics include rapid pursuit, ambush from crevices, and striking with forcipules to inject venom quickly.

Some Scolopendra species can subdue prey of substantial size relative to their body length, using both strength and venom. House centipedes commonly prey on cockroaches and spiders indoors, making them efficient small-scale predators.

Life-history context matters: many species reach sexual maturity in one to two years, while some live several years in the wild and certain tropical Scolopendra have survived five to ten years in captivity.

5. Habitat range and geographic distribution

Centipedes are found on every continent except Antarctica, with the richest species diversity in tropical regions. Roughly 3,300 species are described, and many more likely remain undocumented in remote habitats.

Typical habitats include leaf litter, soil, beneath stones and logs, and human dwellings — the latter often housing Scutigera coleoptrata. Specialized forms live in caves with reduced eyes or along shorelines tolerant of salt spray.

6. Reproduction and developmental patterns

Most centipedes lay eggs, and many groups exhibit anamorphic development: juveniles hatch with fewer segments and add segments and leg pairs as they moult. Clutch sizes range from a handful of eggs to dozens, depending on species and environment.

Parental care appears in numerous taxa: females commonly coil around eggs and sometimes young to protect them for days or weeks. That brooding behaviour increases offspring survival in unstable microhabitats.

Defense & Survival Strategies

Centipedes defend themselves with a mix of speed, venom, camouflage, and occasional limb loss to escape predators. These traits both reduce their risk and help them remain effective hunters.

The next two points describe behavioral escapes and the medical relevance of their chemical defenses.

7. Camouflage, escape, and autotomy

Many centipedes use cryptic coloration and the cover of leaf litter or crevices to avoid detection. When threatened they dart into narrow refuges where larger predators can’t follow.

As a last resort some species autotomize (shed) legs to free themselves from grasping predators. Predators of centipedes include birds, small mammals, reptiles, and larger arthropods, and these defensive options shape predator–prey interactions across ecosystems.

8. Chemical defense and medical implications of venom

Centipede venoms are complex mixes of peptides, proteins, and enzymes that disrupt nervous-system function in prey. The precise cocktail differs by species and has evolved to subdue particular prey types.

In humans most envenomations cause intense local pain, redness, and swelling; occasional cases involve systemic symptoms such as nausea or dizziness. Serious complications are uncommon, though hospital-treated bites from large Scolopendra have been documented in tropical regions.

Because venom peptides target conserved molecular pathways, they’re of interest to biomedical researchers exploring analgesics, antimicrobials, and ion-channel tools for neuroscience.

Interactions with Humans and Scientific Value

Centipedes intersect daily with people as unwelcome sightings, helpful pest controllers, and subjects for scientific study. They play practical roles around homes and contribute to research in pharmacology and robotics.

The next two items highlight benefits for homeowners and why researchers pay attention to these many-legged hunters.

9. Role in pest control and relationship with people

Some centipedes, notably Scutigera coleoptrata (which typically has 15 pairs of legs), commonly enter houses and prey on cockroaches, silverfish, and spiders. Their presence usually signals fewer other arthropod pests.

For homeowners the practical advice is simple: leave small house centipedes alone if you don’t like pests. Avoid handling unfamiliar or large tropical species, and seek medical care if a bite causes severe or unusual symptoms.

10. Scientific research: venom biochemistry and robotic inspiration

Researchers catalogue the characteristics of a centipede to extract two practical lessons: venom peptides as potential biomedical leads, and many-legged coordination as a template for robots that must traverse rubble or dense vegetation.

Laboratories continue to isolate novel venom components that can act on ion channels or microbes, while robotics teams model alternating leg gaits and distributed control to build stable, agile multi-legged prototypes.

Both lines of study turn basic natural-history observations into technical questions with real-world applications.

Summary

- Centipedes display wide anatomical diversity: single leg pairs per segment, leg counts from ~15 to nearly 200 pairs, and specialized forcipules that inject venom.

- They’re primarily nocturnal predators that shape invertebrate communities and can control household pests such as cockroaches and spiders (Scutigera coleoptrata is a common example).

- Defense relies on speed, camouflage, autotomy, and chemically complex venoms that usually cause painful local reactions in humans but are rarely life-threatening.

- Venom biochemistry and many-legged locomotion have practical value for pharmacology and robotics; ongoing research continues to reveal useful peptides and gait strategies.

- Observe centipedes responsibly: appreciate their ecological role, avoid handling unfamiliar species, and follow reputable medical sources for guidance on envenomation.