In 1995, the rediscovery of the tamaraw on Mindoro grabbed headlines and refocused conservation efforts across the Philippines — a reminder that a single species can reshape national priorities. That moment helped crystallize a new public awareness: the archipelago is home to an extraordinary array of endemic species and charismatic wildlife, and a handful of animals do more than inspire pride; they drive tourism, sustain local livelihoods, and signal ecosystem health.

This list of famous animals of the Philippines profiles twelve iconic species grouped into three categories — Endemic Forest Icons, Land Icons (domestic, wild and elusive), and Marine and Coastal Celebrities — explaining each animal’s cultural role, ecological importance, conservation status, and where you can see or support protection efforts. Along the way you’ll find concrete examples (Philippine Eagle Foundation, Mabuwaya Foundation, community hatcheries) and a few hard numbers to show why these animals matter.

Endemic Forest Icons

These land-based endemics live in mature forests and upland habitats; they are often national symbols and are especially sensitive to deforestation and fragmentation. “Endemic” means a species occurs naturally only in the Philippines, and that uniqueness makes protecting remaining forest tracts critical for global biodiversity.

Many forest species here are threatened by logging, agricultural expansion, and hunting. Conservation programs — from captive breeding and rescue centers to protected-area patrols — aim to stabilize populations: the Katala Foundation and the Philippine Eagle Foundation are two NGOs working on species-specific recovery. The country also protects millions of hectares of forest through national parks and reserves, though enforcement and connectivity remain urgent challenges.

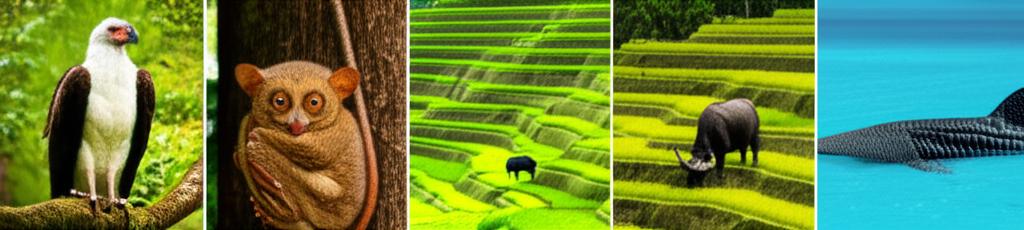

1. Philippine eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi)

The Philippine eagle is the national bird and one of the world’s largest forest raptors, instantly recognizable by its shaggy crest and broad wings. IUCN lists it as Critically Endangered; current estimates describe a very small, fragmented breeding population (estimates vary but are often cited in the low hundreds of mature individuals) — a reminder that this species needs large tracts of intact forest to survive.

As an apex predator, the eagle indicates mature forest health and helps regulate prey populations. Conservation work includes captive-breeding and rehabilitation (Philippine Eagle Foundation) and nest monitoring in Mindanao, Luzon, Leyte and Samar. You can support recovery by donating to vetted groups, following responsible ecotourism practices, and advocating for protected-forest corridors.

2. Philippine tarsier (Carlito syrichta)

The Philippine tarsier is one of the world’s smallest primates, famous for enormous eyes and delicate hands; it has become a symbol of Bohol’s wildlife tourism. IUCN currently lists the species as Near Threatened, with a patchy range across Bohol, Leyte, Samar and nearby islets.

Local sanctuaries (for example, the Tarsier Conservation Area in Corella, Bohol) attract thousands of visitors yearly, providing income for communities but also creating risks from habituation, flash photography and habitat loss. Responsible viewing guidelines — quiet observation, no flash, and maintaining distance — help balance tourism benefits with the species’ sensitivity.

3. Tamaraw (Bubalus mindorensis)

The tamaraw is a dwarf buffalo found only on Mindoro and a potent emblem of Philippine conservation. Classified as Critically Endangered by IUCN, its population has been reduced to small, isolated groups; recent monitoring by the DENR and protected-area staff reports population counts in the low hundreds (estimates vary by year and survey method).

Protecting tamaraw habitat—notably Mount Iglit-Baco National Park—also safeguards other endemic species and watersheds. Community-based patrols, anti-poaching measures and national recovery plans have stabilized some local populations, showing how focused conservation can yield measurable gains.

4. Palawan peacock-pheasant (Polyplectron napoleonis)

The Palawan peacock-pheasant is a visually striking bird restricted to Palawan’s lowland forests. IUCN lists the species as Vulnerable due to its limited range and ongoing habitat loss from logging and conversion.

Its showy plumes and secretive behavior make it a draw for birdwatchers visiting Palawan reserves and community sanctuaries. Conservation measures focus on habitat protection, anti-poaching patrols, and locally guided birding that channels tourism dollars into conservation and community livelihoods.

Land Icons: Domestic, Wild and Elusive

This group mixes domestic cultural icons like the carabao with small, cryptic endemics and rare larger species. These animals shape agriculture, folklore and conservation priorities, and they often sit at the center of human-wildlife conflicts that require local solutions.

Numbers matter: many rural households still rely on carabaos for draft power, while species like the Visayan warty pig and Philippine crocodile survive in small, fragmented populations. Community-based conservation and coexistence strategies are central to both protecting biodiversity and supporting livelihoods.

5. Carabao (Water buffalo)

The carabao is the Philippines’ national animal and a long-standing workhorse on small farms, used for plowing, hauling and transport. While mechanization has reduced reliance in some areas, many smallholder farmers still keep carabaos for fieldwork and as cultural symbols in festivals.

Carabao festivals celebrate the animal’s economic and cultural value, and government programs (breed improvement, veterinary outreach) aim to boost productivity and animal health. Supporting sustainable livestock programs helps rural communities while reducing pressures that can lead to habitat conversion.

6. Visayan warty pig (Sus cebifrons)

The Visayan warty pig once ranged across Panay, Negros and nearby islands but is now Critically Endangered, surviving in small forest fragments. Hunting and habitat loss drove dramatic declines during the 20th century, and remaining populations are isolated and vulnerable.

Captive-breeding programs, zoo partnerships and community awareness campaigns aim to prevent extinction and restore local populations. Recovering the warty pig would also benefit other forest species and help restore ecological functions in remaining lowland forests.

7. Philippine crocodile (Crocodylus mindorensis)

The Philippine crocodile is one of the world’s most threatened crocodilians and is endemic to the archipelago. IUCN lists it as Critically Endangered; only a handful of subpopulations remain, monitored by groups like the Mabuwaya Foundation in Luzon and partner agencies.

Protecting the crocodile conserves freshwater wetlands that local fishers and farmers rely on. Community-based protection, nest monitoring and education have produced local successes, proving that people and crocodiles can coexist when incentives and stewardship are aligned.

8. Philippine mouse-deer / Pilandok (Tragulus spp.)

The pilandok is a tiny, shy ungulate that appears in Visayan folktales and lives in lowland forests and secondary growth. Several local species or subspecies occupy different islands; habitat loss and hunting are the main threats.

Though small and seldom seen, mouse-deer play a role in seed dispersal and forest regeneration. Protecting their habitat through community-managed reserves and including them in local education helps preserve both biodiversity and cultural heritage.

Marine and Coastal Celebrities

The Philippines sits at the heart of the Coral Triangle, which contains roughly 76% of the world’s coral species. Its coastal waters host grand megafauna that attract divers and nature-lovers, but pressures from overfishing, pollution and boat strikes put those animals at risk.

Marine megafauna act as conservation flags: protecting whale sharks, turtles, dugongs and mantas helps conserve seagrass beds, coral reefs and fisheries that millions of people depend on. Local tourism, fisher-led patrols and national agencies (DENR-BFAR, NGOs like WWF) partner on protection and sustainable-use initiatives.

9. Whale shark / Butanding (Rhincodon typus)

The whale shark, locally called butanding, is the world’s largest fish and a major ecotourism draw in Donsol, Oslob and other sites. Globally the species is listed as Endangered by IUCN, and seasonal aggregations can bring significant income to coastal communities.

Tourism benefits can conflict with animal welfare when feeding, close approaches or overcrowding occur. Responsible-viewing rules, boat-operator training and community monitoring (often coordinated with local tourism offices) help reduce disturbance while keeping economic gains for residents.

10. Dugong (Dugong dugon)

The dugong is a gentle seagrass grazer whose presence signals healthy seagrass meadows. IUCN lists dugongs as Vulnerable at the global level, and in the Philippines they face habitat loss, boat strikes and fishing-gear entanglement.

Protecting dugongs requires safeguarding seagrass beds, which store carbon and support fish stocks. Community patrols, seagrass restoration projects and locally managed marine areas in Palawan and parts of the south help maintain the habitats dugongs need.

11. Sea turtles (Hawksbill and Green turtles)

Hawksbill and green turtles nest on Philippine beaches across Palawan, La Union, Davao Oriental and other provinces. Both species are listed as Threatened (hawksbill often Critically Endangered regionally, green turtles Vulnerable), and nesting beaches are critical conservation targets.

Community hatcheries and beach-protection programs have released thousands of hatchlings in some areas, while night patrols and sustainable-tourism guidelines reduce poaching and disturbance. Supporting these local efforts helps protect nesting sites and the coastal livelihoods they sustain.

12. Manta ray (Manta spp.) and mobulids

Manta rays and related mobulids are charismatic filter-feeders valued by dive tourism. Regional protections and research have increased awareness, but bycatch and targeted fisheries for gill plates remain threats in parts of Southeast Asia.

Well-managed dive sites, no-take zones and operator codes of conduct help ensure sightings benefit local economies without harming populations. Popular manta sites in the Philippines provide steady income to dive operators who invest in marine protection.

Summary

- The Philippines hosts an exceptional array of endemic species and iconic wildlife; this article covered twelve flagship animals that shape culture, tourism and conservation.

- Flagship species — from the Philippine eagle and tamaraw to whale sharks and dugongs — both reveal ecosystem health and motivate protection; local NGOs (Philippine Eagle Foundation, Mabuwaya Foundation) and community programs have delivered measurable wins.

- Many species remain threatened by habitat loss, hunting, bycatch and coastal degradation; targeted actions such as protected areas, captive-breeding, community hatcheries and responsible tourism reduce those pressures.

- Practical steps readers can take: support reputable conservation groups, follow viewing guidelines when visiting wildlife, reduce single-use plastics, and choose operators who reinvest in local conservation.

- Want to learn more or help? Consider donating or volunteering with organizations working on these species and their habitats, and spread the word about the value of these famous animals of the Philippines.