At the turn of the 20th century, French and British botanical teams crisscrossed West Africa, pressing specimens and filing reports that first brought widespread attention to the region’s plant richness. Their journals described markets piled with palm fruit, parkland trees laden with nuts, and coastal mangrove belts—early records that still frame how scientists and communities value Guinea’s vegetation.

Guinea’s tropical flora underpins food security, local medicines, timber and non-timber income, and important carbon and coastal defenses. Below are ten representative species and groups—organized as economic staples, ecosystem-shaping trees, high-value timber and NTFPs, and medicinal and cultural plants—that illustrate ecological roles, real-world uses, and present conservation challenges.

Staple and economic species

These species appear in village markets, household farms and roadside stalls and form the backbone of many rural incomes. They supply edible oils, stimulants and nuts, and often support gendered value chains—especially where women lead collection and processing.

1. Oil palm (Elaeis guineensis): West African staple for oil and livelihoods

Oil palm produces palm oil and palm kernel products that fuel cooking, soap-making and small-scale trade across Guinea. Native to West and Central Africa, it supports both smallholder groves tucked near villages and larger commercial plantations.

Smallholders often sell fresh fruit bunches at roadside markets and extract oil using traditional wooden presses or simple mills; processed palm oil also enters informal urban markets. For production figures and yield ranges, see data from the FAO.

Rising demand pressures land use, with conversion of forest and savanna to monoculture a growing concern; sustainable management and smallholder-inclusive planning are essential to curb habitat loss.

2. Shea (Vitellaria paradoxa): women-led value chains and edible fat

Shea trees yield kernels that women collect and process into shea butter, a vital cooking fat and an ingredient for regional and international cosmetics. Estimates by international agencies indicate the shea sector supports millions of people across West Africa, with large proportions of income captured at the community level through collection and artisanal processing (FAO/UN reports).

Collections follow a seasonal rhythm: villagers gather fallen fruits, sun-dry kernels, and boil or roast before manual crushing and extraction. Women’s cooperatives and small enterprises often add value—refining and packaging butter for urban markets or export.

Shea trees commonly grow in parklands and agroforestry mosaics, so managing grazing, fire and selective harvesting helps maintain yields while preserving the scattered tree cover communities rely on.

3. Kola nut (Cola nitida and Cola acuminata): cultural stimulant and cash crop

Kola nuts are chewed as stimulants, exchanged in ceremonies and sold in local markets across Guinea and beyond. They figure in social rituals, hospitality customs and regional trade networks that predate colonial maps.

Smallholder farmers usually cultivate kola within mixed shade gardens or agroforestry systems; fresh nuts move along informal routes to urban centers and regional markets. Price fluctuations and seasonal harvests shape household cash flows.

Because kola is often grown under tree canopies, it fits into diverse land uses that combine food crops, timber trees and cultural plantings—an important model for resilient rural livelihoods.

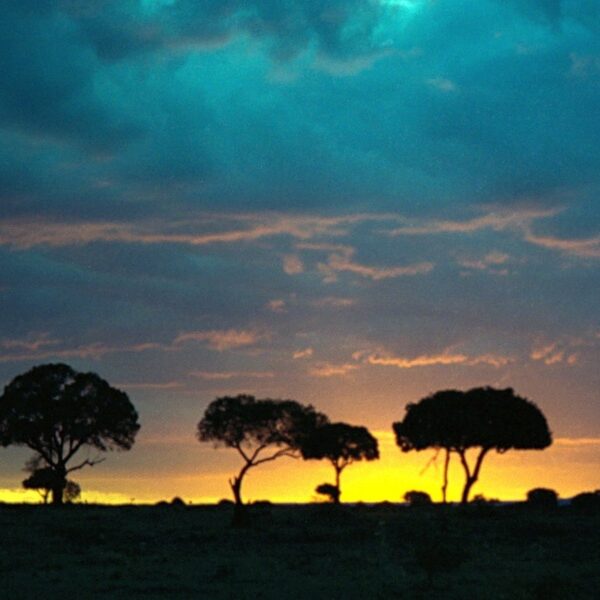

Trees that shape ecosystems

Certain trees and palms act as ecosystem engineers: they stabilize soils and shorelines, feed wildlife, and lock up substantial carbon while providing food, fiber and shelter for people. The next examples show coastal, wetland and savanna-parkland functions that underpin fisheries, agriculture and climate resilience.

4. Baobab (Adansonia digitata): iconic, long-lived multipurpose tree

The baobab, with its huge trunk and millennia-spanning life, supplies fruit pulp rich in vitamin C, oil-bearing seeds and fibrous bark used locally. Villages rely on the fruit season for fresh food and for sun-dried powders that enter markets.

Baobabs serve as living landmarks and sometimes as water storage when trunks hollow; commercial interest in baobab powder and oil has grown in recent years, linking village harvests to export niches. Conservationists have flagged climate-related stress and rare trunk collapses in some regions, so monitoring is active.

5. Raffia palms (Raphia spp.): wetland engineers and craft resources

Raffia palms dominate swampy floodplains and river edges, their stands slowing water flow, trapping sediments and providing shelter for aquatic life. Their long, flexible leaf fibers supply material for mats, baskets and traditional thatch.

Local artisans weave raffia into goods sold in village markets and to tourists; the palms also help maintain nursery habitat for fish that feed coastal communities. Sustainable harvesting—rotating leaf cuts and protecting seed-bearing stands—preserves both livelihoods and wetland function.

6. Mangroves (Rhizophora and Avicennia species): coastal protection and nursery habitat

Guinea’s coastal mangrove belts—dominated by genera such as Rhizophora and Avicennia—shield shorelines from erosion, buffer storm surge and provide nursery grounds for commercially important fish and crustaceans. Mangroves also store disproportionately large amounts of carbon per hectare compared with many upland forests (UNEP).

Fishing communities harvest juvenile fish and use mangrove wood for fuel and small construction projects. Losses from clearance and conversion to agriculture or aquaculture threaten both biodiversity and the fisheries that sustain local diets.

High-value timber and non-timber forest products

Valuable timbers bring income but also create conservation dilemmas: high demand fuels legal and illegal harvest while community needs depend on forest resources. Certification, improved governance and non-timber products offer partial solutions.

7. African mahogany (Khaya spp. / Entandrophragma spp.): prized timber with conservation concerns

African mahogany species produce dense, attractive timber sought by furniture makers and boatbuilders. International demand has historically driven selective logging and export-oriented supply chains, which can deplete mature cohorts if poorly managed.

Local sawmills and loggers supply urban markets while export routes connect to regional buyers; conservation listings and trade rules (see IUCN and CITES where applicable) guide management responses such as community forestry and selective harvest regimes.

8. Iroko (Milicia excelsa) and other durable timbers: locally important, globally traded

Iroko, often called an African teak, supplies long-lived timber for doors, beams and boat planking and is widely used by local carpenters. Its slow growth and canopy role mean sustainable harvest requires long rotations and careful planning.

When communities manage harvests through agreed rules or benefit-sharing schemes, they can retain valuable standing trees while deriving income from selective felling; combining timber management with non-timber products often smooths cash flows between rotations.

Medicinal and culturally significant plants

Plant-based traditional medicine remains a primary health resource in many parts of Guinea, and cultural ties to trees and shrubs weave into rituals, crafts and food customs. Several species have attracted scientific interest for active compounds, but local preparation methods and quality control vary widely.

9. Kapok / Ceiba (Ceiba pentandra): cultural, fiber, and ceremonial uses

Ceiba pentandra grows into a towering village landmark whose kapok fiber fills mattresses and cushions and whose canopy provides welcome shade. Communities often attach cultural significance to large kapok trees, holding ceremonies and meetings beneath them.

Ecologically, kapok flowers feed bats, bees and birds, aiding pollination and seed dispersal. The fiber sees both traditional use and occasional commercial applications, though synthetic alternatives have reduced some market demand.

10. Local medicinal shrubs (e.g., Cryptolepis sanguinolenta and other ethnobotanical species)

Shrubs and herbs supply decoctions and infusions for fevers, digestive complaints and wounds; ethnobotanical surveys across West Africa regularly record species such as Cryptolepis sanguinolenta used for febrile illnesses. Some of these plants have been investigated in peer-reviewed pharmacological studies for antimalarial and antimicrobial activity (WHO and academic literature).

Traditional healers prepare remedies from leaves, roots or bark, but dosage, purity and safety can vary. Where promising compounds are identified, ethical sourcing and benefit-sharing with local communities are crucial before commercial development.

Summary

- Guinea’s plant life supplies food, fuel, fiber and medicine while delivering key ecosystem services—carbon storage, shoreline protection and habitat for fisheries.

- Crops like oil palm, shea and kola underpin household incomes and markets; many value chains (notably shea) are driven by women collectors and processors linked to international demand.

- Tall, long-lived trees and palms—baobab, raffia, mangroves and kapok—shape landscapes and livelihoods, but face pressure from land conversion and unsustainable harvest.

- Sustainable management, community stewardship, and credible tools such as certification and protected-area enforcement can balance economic benefits with conservation; organizations such as FAO, IUCN and UNESCO are useful starting points for best practices and further reading.