The Republic of Seychelles comprises 115 islands spread across the western Indian Ocean, and that small land area hosts a surprisingly rich and unique plant life.

On tiny granite hills and low coral atolls, endemic palms, seabird-fed forests and useful shoreline trees provide food, shelter and cultural material for island communities — and many species are conservation icons. Vallée de Mai on Praslin (UNESCO 1983) is one famous example where island plants are protected and celebrated.

Why care? Endemic species embody evolutionary history, plant communities deliver services like shoreline protection and fish nurseries, and local uses (from woven baskets to tamanu oil) tie plants to livelihoods. This article profiles seven representative plants and plant groups to show how Seychelles plant life supports people and wildlife and why active conservation matters.

Iconic Endemics: Symbols of Seychelles’ Plant Heritage

Island endemics often become national symbols because they occur nowhere else and visibly shape landscapes. On the granitic inner islands a handful of plants — especially palms — dominate the imagination and conservation effort. Vallée de Mai (UNESCO 1983) remains the best-known reserve, where intact palm groves and understory plants show classic island biogeography in action.

1. Coco de Mer (Lodoicea maldivica): The giant-seeded wonder

The coco de mer is perhaps the Seychelles’ most famous plant, famed for producing the largest seed in the plant kingdom. Individual seeds can weigh up to about 30 kg, and mature trees occur naturally almost exclusively on Praslin and nearby Curieuse.

Those huge, heart-shaped nuts and the palms themselves are cultural emblems — they appear on stamps, coins and souvenirs — and draw visitors to protected groves such as Vallée de Mai. Park guides still remark that many tourists “stop in their tracks” at first sight, a reminder of the species’ appeal.

Because of its rarity and tourist value, the coco de mer is tightly regulated: seeds and whole palms cannot be exported without permits, and protected areas and local laws aim to curb illegal trade and habitat loss.

2. Seychelles Fan Palm (Phoenicophorium borsigianum): The understorey specialist

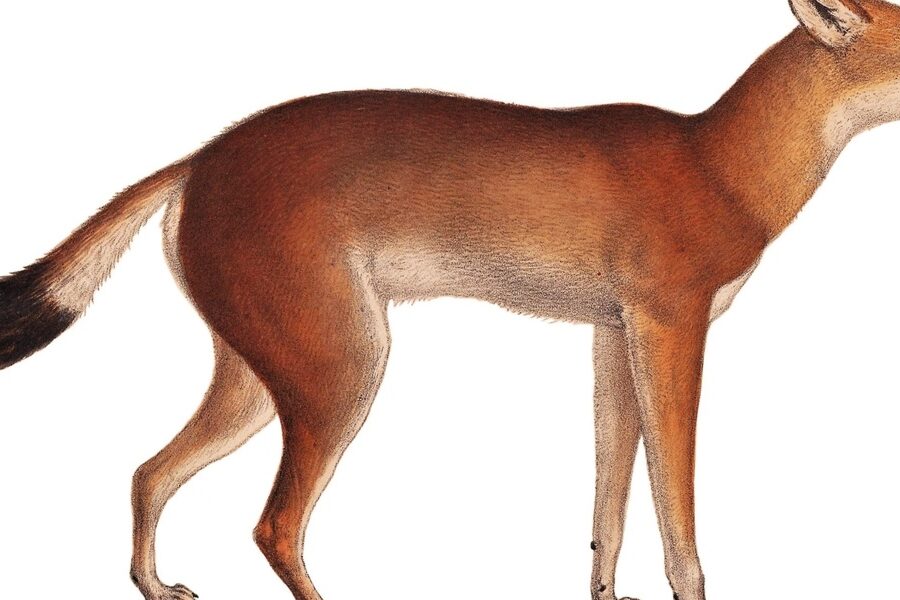

The fan palm is a widespread endemic on the granitic islands, often forming dense understorey stands on Mahé, Praslin and nearby islands. Its compact, wind-tolerant form makes it well suited to coastal slopes and exposed ridges.

Locally, fronds are harvested for traditional weaving — baskets, mats and simple roofing — sold in island markets and at craft stalls. Those products provide income and preserve craft knowledge while connecting people to native plants.

Threats include development pressure and invasive plants that change understorey light and competition, so sustaining fan-palm groves is a conservation priority for maintaining both biodiversity and cultural crafts.

3. Seychelles Pandanus (Pandanus sechellarum): Coastal screwpine with island niches

Pandanus is a distinctive coastal and near-shore plant with prop roots and spiralled leaves that often line beaches and rocky shorelines. Its structure helps trap sediment and stabilise shorelines after storms.

Leaves are used locally for weaving mats and thatch, and dense Pandanus stands form useful windbreaks and habitat for coastal birds. In many places these plants act as a first line of defence against erosion and salt spray.

Maintaining Pandanus belts supports shoreline resilience and cultural uses, but pressure from development and shoreline modification can reduce their protective role.

Coastal and Atoll Flora: Plants that Shape Coral Island Life

Vegetation on the granitic inner islands differs strongly from coralline atolls and outer islands. Atolls like Aldabra (UNESCO 1982) host plant communities shaped by salt spray, seabird nutrient inputs and low, porous soils. Two plant groups stand out for their ecosystem roles: seabird-associated trees such as Pisonia and mangrove species like Avicennia marina.

4. Pisonia grandis: Seabird forests that recycle the ocean

Pisonia grandis often dominates low coral islets where dense seabird colonies nest in the canopy. Bird droppings (guano), feathers and food remains bring marine nutrients ashore, fertilising soils and allowing Pisonia to grow in otherwise nutrient-poor substrates.

Those seabird forests are keystone habitats: they sustain terns, noddies and other colonial nesters, and by concentrating nutrients they help support nearby fisheries indirectly. Where rats or human disturbance arrive, nesting success can crash and the whole nutrient cycle unravels.

Conservation work often focuses on invasive predator removal and access control to protect nesting colonies and the Pisonia stands they depend on — restoring even a small islet can quickly boost seabird numbers and plant health.

5. Mangroves (Avicennia marina and associates): Coastal defense and nursery habitat

Mangroves line sheltered lagoons and tidal creeks across the inner islands and atolls. Avicennia marina is a common, salt-tolerant species that forms dense stands in intertidal zones and helps trap sediment.

Healthy mangroves provide nursery habitat for juvenile fish and crustaceans, store carbon in their soils, and reduce wave energy during storms — benefits that directly support fisheries and protect coastal settlements.

Still, mangroves are sensitive to sea-level rise, sediment changes and coastal development, so conserving them is central to atoll resilience and local livelihoods.

Useful Plants, Medicine and Restoration: People and Plants

Many Seychelles plants have direct human uses — traditional medicine, timber, shade and artisan materials — and they’re also central to restoration projects that rebuild degraded forest. Local botanical knowledge and nursery networks are vital for island resilience.

6. Takamaka (Calophyllum inophyllum): Traditional medicine meets modern skincare

Takamaka is a common shoreline tree valued for shade, timber and the oil extracted from its seeds. Tamanu (takamaka) oil has a long history of topical use for wound care and skin ailments.

Today tamanu oil appears in boutique natural skincare lines and artisanal balms sold in island markets. Small community presses and cottage producers make salves and oils that are purchased by visitors and exported in limited runs, connecting traditional knowledge to local incomes.

Protecting takamaka stands preserves a resource that serves health, shade and small-scale enterprise while buffering shorelines from erosion.

7. Native species in restoration: nurseries, replanting and island recovery

Restoration programs on Mahé, Praslin and other islands increasingly rely on native palms, canopy trees and shrubs grown in community and government nurseries. Seedlings of endemic palms, Pandanus and canopy species are planted on degraded slopes and coastal sites to rebuild structure.

Benefits include improved watershed protection, carbon storage and the return of native birds and insects. Multi-year planting runs and community nursery training have led to measurable habitat gains and the reappearance of nesting sites in several restored patches.

Long-term success depends on local involvement, proper species selection and maintenance — restoration is ecological work and social work rolled together.

Summary

- The Republic’s 115 islands support a remarkable range of plant communities, from coco de mer groves to mangrove fringes.

- Coco de Mer (seeds up to about 30 kg) and fan palms are cultural and ecological icons protected in places like Vallée de Mai (UNESCO 1983).

- Pisonia seabird forests and mangroves (Avicennia-dominated stands) transfer marine nutrients and protect fisheries and shorelines.

- Takamaka oil links traditional medicine to artisanal products, and native nurseries are restoring habitat and supporting livelihoods.

- Protected sites such as Aldabra (UNESCO 1982) show that concerted conservation can keep island plant communities intact.

Learn more about The flora of the seychelles by supporting local nurseries and conservation groups, visiting protected sites responsibly, or checking UNESCO and island NGO resources.