Since 1970, monitored wildlife populations have declined an average of 69% globally (WWF Living Planet Report, 2022). That stark number is the beginning of a cautionary story: slow, steady losses that suddenly become crises—think the Atlantic cod fishery, which collapsed after decades of overfishing and led Canada to declare a moratorium in 1992.

Those losses matter because ecosystems provide food, clean water, flood protection and much more. A community that misses early warnings pays later—in livelihoods, safety, and money. Below are eight concrete, observable signs of ecosystem imbalance—biological, physical, human-driven and functional—to watch for and act on.

Biological Indicators

Changes in who lives where—the loss of native species or sudden spikes of newcomers—are often the earliest, most visible signs that an ecosystem is losing resilience. These biological indicators are the ones neighbors and scientists alike notice first, and they can trigger practical responses.

1. Declining native species populations

Population declines of keystone or once-common native species are a top sign of imbalance. The WWF Living Planet Report found an average 69% decline in monitored wildlife since 1970, a broad signal of shrinking resilience.

The Atlantic cod collapse—culminating in a 1992 Canadian moratorium after decades of overfishing—shows how declines can build slowly and then devastate fisheries-dependent communities. Monarch butterflies and many insectivorous birds have shown multi-decade downward trends too.

Practical things to monitor: repeated standardized surveys, catch-per-unit-effort from fisheries, and citizen-science sighting records. Early detection supports measures like catch limits, seasonal closures, protected areas and targeted recovery programs that can reverse trends.

2. Invasive and opportunistic species spreading

The sudden arrival and rapid spread of non-native or opportunistic species often follows disturbance or stress. Economically and ecologically, invasives are costly—some U.S. estimates (Pimentel and others) put annual damages and management near $100–120 billion.

Examples are familiar: zebra mussels clog water intakes and alter lake food webs in North America, and cane toads in Australia rewired predator–prey dynamics after introduction. Invasives can change nutrient cycling, outcompete natives and signal weakened ecosystem resistance.

Managers can act with early-detection networks, boat-cleaning protocols, rapid response teams and public reporting hotlines. Stopping a new invader early is almost always far cheaper and more effective than trying to control it after it’s widespread.

Physical and Chemical Signals

Shifts in soils, water chemistry and other abiotic factors often precede or accompany biological declines, and they’re trackable with instruments and satellites. Watch for measurable changes—soil loss, turbidity spikes, or expanding hot spots of poor water quality—and act early.

3. Soil degradation, erosion, and loss of topsoil

Visible gullying, wind-blown dust, or measurable declines in soil organic matter are strong indicators that an ecosystem’s capacity to support plants and hold water is eroding. The FAO estimates about one-third of the world’s soils are degraded.

The Dust Bowl of the 1930s is an extreme historical example; today, unsustainable cropping and removal of perennial cover cause local topsoil loss in many regions. Consequences include lower yields, more sediment in rivers, and larger runoff events.

Farmers and land managers can look for reduced infiltration, more surface runoff, declining yields, and increased dust. Solutions that work: cover crops, reduced tillage, mulching, agroforestry and riparian buffers to trap sediment and rebuild organic matter.

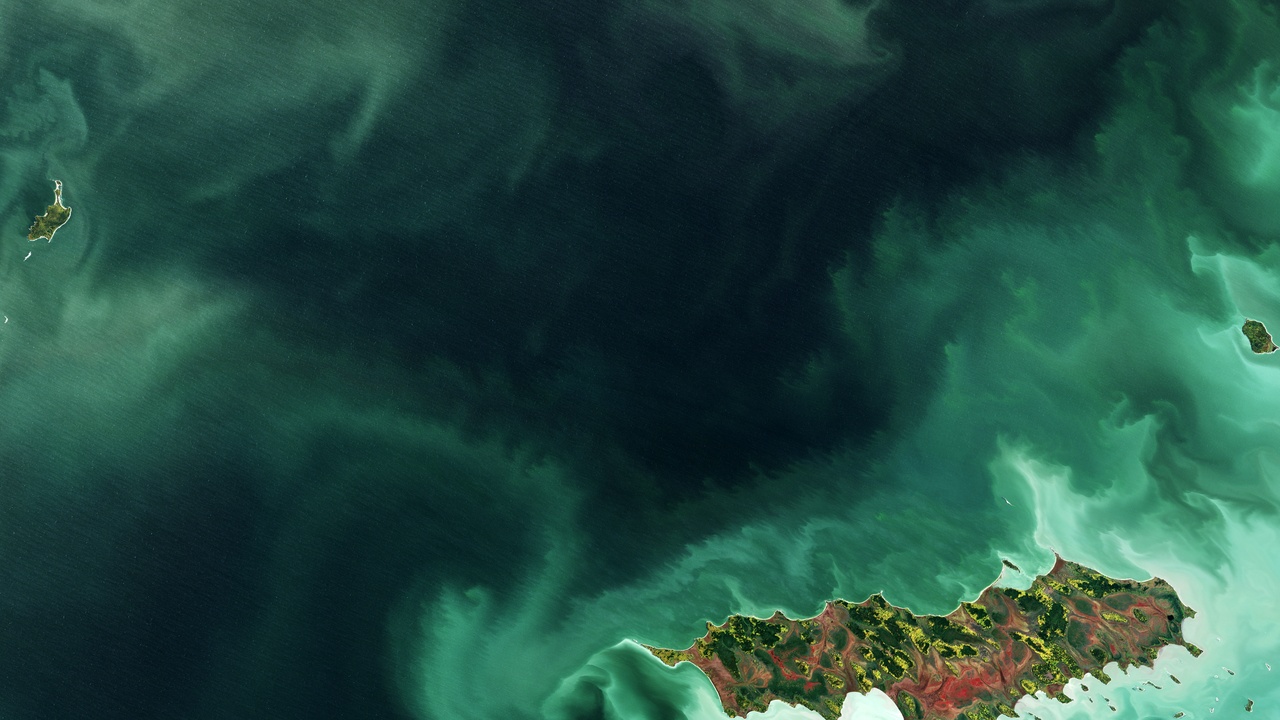

4. Worsening water quality and frequent algal blooms

Spikes in nutrient-driven algal blooms, persistent turbidity or recurring fish kills signal aquatic ecosystems under stress. The 2014 Lake Erie bloom that shut down Toledo’s drinking-water supply is a clear wake-up call.

Coastal hypoxic “dead zones,” like the seasonal Gulf of Mexico area that can span thousands of square miles, reflect nutrient overloads and altered food webs. Effects include fisheries closures, lost tourism and public-health risks.

Simple community indicators: sharp declines in water clarity, foul odors, frequent fish kills or algal mats. Management responses include nutrient-reduction plans, riparian buffers, improved wastewater treatment and better fertilizer practices on farms.

Human and Land-Use Signals

Human footprints—clearing, development and pollution—are often the most direct causes of imbalance. Rapid land-cover change and persistent waste accumulation remove habitat, fragment populations and alter how water moves across the landscape.

5. Rapid land-use change and deforestation

Clear-cutting, urban sprawl and conversion to agriculture can remove habitat faster than species can adapt. Recent Amazon monitoring (INPE and similar efforts) has documented spikes in deforestation, reaching tens of thousands of square kilometers in some years.

Consequences include fragmentation, edge effects and local extinctions as corridors disappear. Satellite time-series, change-detection maps and local land-use records are effective early-warning tools for planners and conservationists.

Actions that help: enforce protected areas, restore connectivity via corridors, zoning that limits conversion, and incentives for sustainable land management that keep working landscapes hospitable for wildlife.

6. Accumulation of pollution and plastic waste

Roughly 8 million metric tons of plastic enter the ocean each year (Jambeck et al., 2015), and persistent chemicals—heavy metals, PCBs and other pollutants—build up in food webs. These inputs create long-term health and ecological problems.

Microplastics show up in seafood, contaminants concentrate in top predators, and shorelines can become clogged with debris. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch and routine shoreline surveys make the problem visible.

Communities can respond with better waste management, bans on certain single-use plastics, extended producer responsibility policies and cleanup programs. Monitoring shoreline debris and contaminant levels in fish helps target interventions.

Disrupted Ecological Processes and Functions

Ecosystems are defined by processes—pollination, nutrient cycling, disturbance regimes. When those processes degrade or shift timing, the whole system’s function changes. Keep an eye on the roles species play and how disturbances are changing.

7. Declines in pollinators and other functional groups

Losses among pollinators, soil microbes or decomposers are less dramatic to spot but critical. IPBES and regional studies document substantial declines in many insect groups and pollinators across multiple regions.

Pollinator declines reduce crop yields and wild-plant reproduction, while declines in soil and detritus organisms slow nutrient cycling. Farmers might notice fewer flower visits, lower fruit set or fewer larvae in monitoring traps.

On-the-ground fixes include restoring native floral resources, reducing pesticide use, creating hedgerows and pollinator corridors, and protecting nesting habitat. These actions often pay off in both biodiversity and productivity gains.

8. Trophic cascades and altered disturbance regimes

Trophic cascades happen when changes at one level ripple through the food web. Yellowstone’s wolf reintroduction is a classic case where predators reshaped herbivore behavior and vegetation, demonstrating how linked systems are.

Contrast that with places where predator loss led to overgrazing and vegetation collapse. At the same time, disturbance regimes are shifting—western North America has seen increases in annual area burned since the 1980s, altering landscapes and recovery patterns.

Monitoring options: predator–prey surveys, fire-frequency records and post-disturbance vegetation sampling. Management tools include targeted reintroductions, managed burns, landscape-scale fuel management and restoring natural connectivity.

Summary

- Biological changes—declines or invasive outbreaks—are the most visible early warnings and often reveal deeper physical or human drivers.

- Abiotic signals, like soil loss and algal blooms, are measurable with instruments and satellites and provide reliable early-warning data for action.

- Land-use change and pollution (including plastic inputs) create chronic pressure that cascades through food webs and local economies.

- Functional disruptions—pollinator declines, trophic shifts, altered fire regimes—change how ecosystems work and require process-focused management to restore balance.

- Spotting these signs early lets communities support monitoring, back targeted policies, and take practical steps like planting natives, reducing runoff, and restoring corridors.