In the Victorian era, botanical explorers sent home entire trunks of strangling lianas and packets of delicate tendril specimens, baffling gardeners who tried to treat all climbing plants the same way.

That confusion still shows up in modern gardens. Gardeners, landscapers, and ecologists need to know whether a plant will add weight, cling to brick, return every spring, or vanish with frost. Practical decisions—what support to build, when to prune, and which species to favor for habitat—depend on these differences.

This piece lays out 8 differences between vines vs climbers grouped into three parts: biological and morphological traits, growth and seasonal behavior, and practical/ecological implications. Each point includes examples and clear takeaways you can use when selecting and managing climbing plants.

Biological and Morphological Differences

Many of the clearest distinctions start with plant form—stem type, leaves, and attachment organs. Some climbers are herbaceous and short-lived above ground; others are woody lianas that persist and thicken year after year.

Those basic differences affect weight, pruning, and where a plant can be grown. Below are three specific morphological contrasts with examples and practical tips.

1. Stem structure: woody lianas versus herbaceous climbers

Some climbing plants develop woody, long-lived stems (lianas) while others remain herbaceous and die back each season.

Woody lianas can produce stems several centimetres across and persist for decades, adding substantial mass to fences and host trees. Herbaceous climbers tend to have thinner shoots and regrow from roots or crowns each year.

That difference matters for pruning and supports. A heavy, woody wisteria will need a robust, load-bearing pergola and regular structural pruning; a morning glory can be trained on lightweight netting and pulled out at season’s end.

For more on woody climbers and their management see resources from Kew Gardens and pruning guidance at the Royal Horticultural Society.

2. Attachment organs: tendrils, adhesive roots, and twining stems

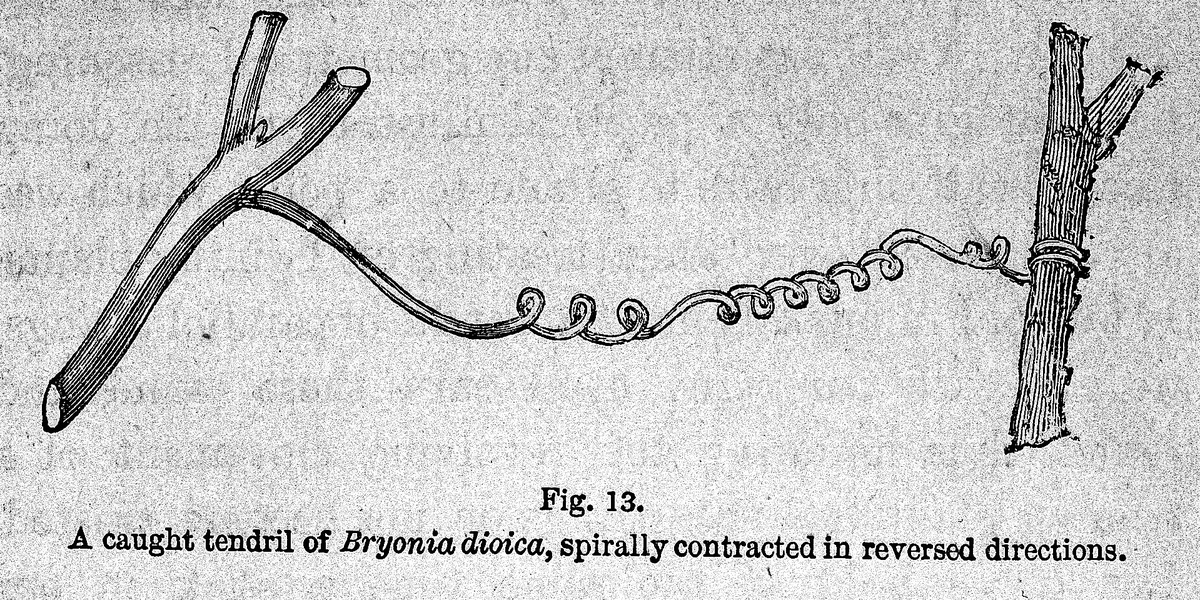

Climbers attach using different tools: slender tendrils, adhesive rootlets or pads, and stems that twine around supports.

Tendrils coil when they touch an object (a thigmotropic response), allowing plants like grapevine to grip thin wires or lattices. Plants such as Parthenocissus (Boston ivy) form adhesive pads that stick to masonry. Twining stems (honeysuckle, morning glory) wrap around rods or other plants.

Attachment type determines the climbing substrate you can use. Tendril climbers do well on open trellis; adhesive climbers will cling to smooth walls but can damage mortar over time. Avoid adhesive species on historic brick and choose trellis material to match the mechanism.

See practical notes on attachment and masonry from the RHS and regional extension services for repair risks.

3. Leaf and organ modifications: tendrils, petiole changes, and specialized structures

Many climbers have leaves or leaf parts modified to aid climbing and light capture.

Peas and sweet peas turn leaflets or stipules into tendrils that seek supports. Some passionflowers (Passiflora) pair dramatic leaf shapes with grasping organs. Others reduce leaf area and put resources into thickened stems for water storage.

Knowing whether tendrils come from leaflets or stems helps identify the plant and suggests training methods. For example, tendril climbers need close, evenly spaced supports where a twining stem might only need a single pole.

Growth Strategies and Seasonal Behavior

Climbing plants use a range of strategies to reach light while reducing investment in supportive tissue. These choices determine growth rate, seasonal habit, and reproductive placement.

Below are three behavioral traits—energy allocation, seasonal habits, and where plants put their flowers and fruit—with practical notes on timing and garden use.

4. Energy allocation: investing in vertical reach rather than supportive tissue

Many climbers allocate proportionally less biomass to trunks and more to rapid shoot elongation so they can reach canopy light quickly.

That trade-off lowers the carbon and time cost of building heavy support tissue. In practice, climbers can produce long annual shoots quickly—grapevine can add 30–50 cm of new growth in a week during peak season—so lightweight supports often suffice early on, but long-term woody vines will demand sturdier structures.

Match support strength to expected long-term load: temporary netting for annuals, welded frames or beams for heavy lianas. See viticulture and arboriculture notes at UC ANR for growth-rate guidance on common vineyard cultivars.

5. Seasonal strategies: deciduous versus evergreen climbers

Some climbers are deciduous and die back to the root in winter; others keep foliage and structure year-round.

Deciduous types like wisteria offer strong spring displays and are usually pruned in late winter when dormant. Evergreens such as English ivy provide winter cover and habitat but can conceal damage and conceal pests.

Plan seasonal maintenance accordingly: prune deciduous climbers in their dormant window; monitor evergreen covers to prevent hidden rot or structural strain.

6. Reproductive placement: flowers and fruit in the canopy versus near the ground

Many climbers position flowers and fruit high in the canopy to attract pollinators and seed dispersers that move through the treetops.

This placement affects ecology and harvest. Fruit up in the canopy is more visible to birds and bats, aiding dispersal and forest regeneration. In a garden, trellised grape clusters are easier to harvest when training puts the fruit within reach.

Positioning for pollinators also matters. Showy Passiflora flowers placed on uprights catch hummingbirds and bees, so place those vines where pollinators can access them.

Practical, Ecological, and Management Implications

Biological traits translate directly into real-world outcomes: structural risk to buildings and trees, benefits for wildlife, and the potential for some climbers to become invasive.

The two points below focus on damage risk and the balance between useful species and those to avoid.

7. Structural impact: weight, host damage, and building risks

Woody vines can add substantial weight to host trees and structures, and adhesive climbers can damage mortar, paint, and siding.

Reported cases from building-conservation and arboriculture sources note that mature woody vines can impose loads measured in tens to hundreds of kilograms on fences and small trees, and roots or adhesive pads may loosen mortar joints over years (see guidance from RHS and regional arboriculture services).

Management tips: inspect attachment points annually, use sacrificial trellis systems that keep vines off masonry, and avoid planting adhesive species on historic walls. For heavy lianas, design supports as you would for a small tree—stout posts, firm anchoring, and access for pruning.

8. Uses and benefits versus invasiveness: ornamental value, habitat, and risks

When choosing between vines vs climbers for a site, balance the clear benefits—shade, screening, nectar and fruit for wildlife—against invasive potential.

Some species are invaluable in restoration and gardens. Native clematis and Vitis species supply nectar and fruit for birds. By contrast, species such as kudzu and Japanese honeysuckle can spread rapidly; kudzu, for example, is known to grow up to about a foot per day in ideal conditions and has covered large tracts in parts of the U.S. Southeast according to USDA reports.

Practical advice: favor native climbers for habitat creation, avoid known invasives in vulnerable regions, and check local extension or invasive-species councils for region-specific lists and control methods.

Summary

- Stem type and attachment method drive maintenance: woody lianas need strong supports and regular structural pruning; herbaceous climbers can use lightweight trellis.

- Attachment organs matter—tendrils, twining stems, and adhesive pads determine suitable supports and potential building damage.

- Seasonal habit and reproductive placement affect pruning timing, wildlife benefits, and harvest accessibility.

- Weigh benefits against risks: choose native species for habitat and erosion control, avoid invasives like kudzu where they’re a problem, and consult local extension for recommendations.

- Practical next steps: pick trellis type to match attachment, inspect structures annually, and contact your local extension or arboretum for species suited to your site.