In 2005 Coiba National Park earned UNESCO World Heritage status, and that recognition spotlighted Panama’s extraordinary role as a biological bridge between North and South America. The country packs rainforest, cloud forest, mangrove and rich marine realms into a compact landmass, so you can study big‑cat ecology, cloud‑forest birds and sea turtles within a few hours’ travel. That concentration makes Panama an efficient living laboratory for conservation and one of the hemisphere’s best places for nature tourism. This list highlights 12 emblematic species that illustrate Panama’s biodiversity, their ecological roles, cultural meaning and the conservation challenges they face. The entries are grouped by habitat: Rainforest mammals, Colorful birds, Reptiles & amphibians, and Coastal & marine life. Let’s start with the mammals that anchor Panama’s forests.

Rainforest Mammals

Panama’s forests are biologically rich because the isthmus connects continental faunas and still contains important intact corridors such as the Darién (a UNESCO biosphere reserve) and long‑protected areas like Soberanía National Park (established 1980). Roughly 60% of the country remains forested, sustaining large mammals that move seeds, control herbivore numbers and shape vegetation structure (STRI; IUCN). These species underpin ecotourism—camera‑trap safaris and guided hikes draw researchers and visitors alike—and they maintain the ecosystem processes that downstream communities rely on. Yet habitat loss, hunting and road fragmentation threaten those connections. Below are three rainforest mammals that epitomize those roles and pressures.

1. Baird’s Tapir (Tapirus bairdii) — The forest gardener

As Panama’s largest terrestrial herbivore, Baird’s tapir functions as a forest gardener, transporting seeds across long distances and opening light gaps by feeding on understory plants. The species is listed as Endangered by the IUCN and occurs in western Darién, Cerro Hoya and scattered lowland sites. Adults typically measure about 1.8–2.5 m in length and weigh roughly 150–300 kg, giving them the bulk to move large seeds. Camera‑trap studies in Darién and community monitoring programs have documented local declines, prompting corridor proposals to reconnect subpopulations (IUCN; local NGOs). Conservation efforts now emphasize protected corridors and camera‑trap monitoring to track recovery.

2. Jaguar (Panthera onca) — Apex predator and landscape indicator

The jaguar is Panama’s top carnivore and an indicator of intact habitat, preying on peccaries, deer and other medium mammals and helping regulate herbivore populations. Male home ranges in Central American forests often exceed 50 km², and jaguars are listed as Near Threatened by the IUCN at a continental scale. Sightings and camera‑trap records concentrate in Darién and the protected watersheds around Coiba, helping justify new reserves and funding for anti‑poaching patrols. Indigenous communities in eastern Panama also revere the jaguar in cultural traditions, which strengthens local support for corridor initiatives and ecotourism programs started in the 2010s.

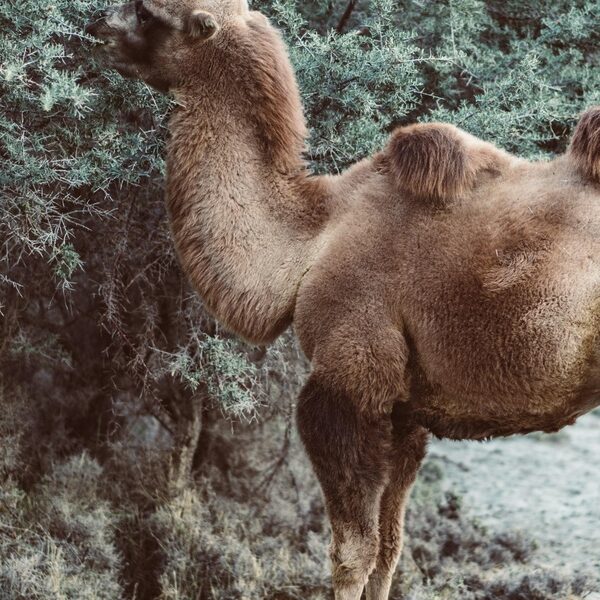

3. Three-toed Sloth (Bradypus variegatus) — Slow-moving specialist of the canopy

The three‑toed sloth is an arboreal specialist and an instantly recognizable symbol of Panama’s canopy life. It feeds almost exclusively on leaves, hosts a microecosystem of algae and moths in its fur, and moves at an average speed of roughly 0.24 km/h while sleeping up to 15 hours per day. By concentrating nutrients in small areas and providing habitat for commensal species, sloths contribute to nutrient cycling and canopy biodiversity. They’re popular with tourists on Gamboa rainforest tours, and rescue centers and rehabilitation programs routinely rehabilitate injured sloths for release back into Soberanía and neighboring reserves.

Colorful Birds

Panama is a birdwatcher’s paradise because it sits on major migratory flyways, spans habitats from cloud forest to mangrove, and hosts renowned birding corridors such as Pipeline Road in Soberanía and the isles of Bocas del Toro. Birding draws thousands of international visitors annually and supports local guide cooperatives and eco‑lodges (STRI, local operators). The nation’s mix of resident specialists and seasonal migrants makes it possible to see cloud‑forest jewels and coastal species in one trip. Below are three birds that represent color, raptor power and montane charm.

4. Resplendent Quetzal (Pharomachrus mocinno) — Cloud-forest jewel

The resplendent quetzal is a high‑elevation cloud‑forest specialist prized by photographers and birders, commonly seen in higher areas such as Volcán Barú and other montane reserves between roughly 1,200–3,000 m. Quetzals nest in tree cavities and feed on fruits and small animals, helping disperse seeds of mountain trees. Their presence indicates intact montane habitat and healthy watershed protection—when cloud forest is conserved, downstream communities benefit from more reliable water supplies. Highland ecotourism focused on quetzal viewing brings photographers and guides to reserves that protect both species and people.

5. Scarlet Macaw (Ara macao) — Flash of color and social intelligence

Scarlet macaws are unmistakable: large, red‑and‑yellow parrots that travel in noisy social flocks and nest in old, tall trees. Key populations remain in eastern Panama, where community monitoring and protection programs have reduced nest disturbance and supported limited reintroduction efforts in the 2000s. Macaws are vulnerable to the pet trade and habitat loss, but protected areas and eco‑lodges offering guided macaw sightings have generated income for local communities and spurred craft traditions that celebrate the birds.

6. Harpy Eagle (Harpia harpyja) — Powerful canopy hunter

One of the Americas’ largest raptors, the harpy eagle is a canopy specialist that preys on monkeys and sloths and requires expansive tracts of mature forest to breed. Wingspans approach 2 m, and the species is considered Near Threatened in many parts of its range. Sightings in Darién and eastern forests have helped spur canopy conservation and rehabilitation efforts; local NGOs and raptor rescue centers document nest sites and work with communities to protect nesting trees. The harpy’s presence signals long‑term habitat quality and gives conservation groups a charismatic ambassador for forest protection.

Reptiles & Amphibians

Panama boasts an exceptional array of herpetofauna, from brightly colored poison dart frogs to large constrictors. Amphibians here are both charismatic and imperiled: chytrid fungus began driving steep declines in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and species like the Panamanian golden frog became emblematic of that crisis. Reptiles and amphibians matter for pest control, cultural traditions and biomedical research—frog alkaloids have informed drug leads—and their status is a sensitive barometer of ecosystem health (IUCN; AmphibiaWeb). Captive‑breeding and field surveys remain central to recovery efforts.

7. Panamanian Golden Frog (Atelopus zeteki) — Symbol of crisis and conservation

The Panamanian golden frog is a national symbol and one of the most visible casualties of chytridiomycosis, with dramatic declines beginning in the late 1990s and major population crashes reported around 2004. The species is considered Critically Endangered and is functionally extinct in the wild in some accounts, which led to captive‑breeding programs in the 2000s (Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project). Those ex situ populations underpin biosecurity research and public outreach, and the frog has become a powerful rallying point for amphibian conservation across the region.

8. Poison Dart Frogs (Dendrobatidae) — Tiny chemists with outsized importance

Poison dart frogs are small, brightly colored amphibians known for potent alkaloid toxins—species such as Oophaga and Dendrobates occur in Panama’s leaf litter and streamside habitats. Panama hosts dozens of dendrobatid populations with varied color morphs, and researchers study their alkaloids for potential biomedical applications. These frogs are voracious insect predators and sensitive indicators of microhabitat quality, so conserving streamside forest and leaf litter preserves both amphibian diversity and the research potential their chemistry offers.

9. Boa Constrictor (Boa constrictor) — Generalist predator of forests and edges

Boa constrictors are adaptable, medium‑large snakes found from pristine forest to agricultural edges, where they prey on rodents, birds and small mammals. Adults commonly reach 2–3 m in length, and their role as natural rodent controllers can reduce crop losses for small farmers. Human‑wildlife conflict sometimes leads to unnecessary killing, so outreach and rescue/relocation programs work to reduce persecution. Field studies and local education campaigns highlight boas’ ecosystem role and provide practical alternatives to lethal responses.

Coastal & Marine Species

Bordered by both the Caribbean and Pacific, Panama supports distinct coastal communities and marine corridors such as the Gulf of Chiriquí and Bocas del Toro. Coastal habitats—mangroves, coral reefs and sandy beaches—sustain fisheries, protect shorelines and support tourism. Marine protected areas like Coiba National Park (UNESCO site, 2005) and regional reserves help safeguard spawning and nursery grounds. Yet overfishing and coral bleaching threaten productivity, so fisheries management and reef monitoring are now priorities for coastal resilience and livelihoods (local fisheries agencies; UNESCO).

10. Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia mydas) — Long-distance migrant and beach guest

Green sea turtles nest on both Caribbean and Pacific beaches in Panama and forage in nearshore seagrass beds. Nesting seasons vary by coast but generally peak between June and September, and average clutch sizes are around 80–120 eggs. Threats include egg poaching, coastal development and bycatch, but community‑led nest monitoring and protection programs have achieved local successes on several beaches. Volunteer programs and NGOs coordinate nightly beach patrols and record seasonal nesting counts to guide protection efforts.

11. Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) — Seasonal ocean visitor and draw for boat-based tourism

Humpback whales migrate along Central American coasts, arriving in Panamanian waters mainly during the boreal winter and early spring—roughly December through April—to breed and calve. Observers in Bocas del Toro and the Gulf of Chiriquí report breaching, singing and small groups typically of 2–6 animals during peak months. Responsible whale‑watching operations offer economic benefits to coastal communities while research projects monitor movements and assess risks like ship strikes and entanglement, informing safer boating practices.

12. American Crocodile (Crocodylus acutus) — Coastal predator between mangroves and estuaries

The American crocodile inhabits estuaries and mangrove coastlines on both coasts of Panama, with adults commonly reaching 3–4 m. They nest on sandy banks and help structure fish communities through predation and habitat engineering. Coexistence programs—nest protection, signage and community education—have reduced conflict in several estuaries, and some monitoring programs have been active since the early 2000s to track population trends and nesting success. Protecting mangroves benefits crocodiles and the fisheries and shorelines people depend on.

Summary

- Panama concentrates remarkable biodiversity in a small area—rainforest, cloud forest, mangroves and rich marine zones—making conservation efforts especially high‑impact.

- Certain species act as ecosystem engineers or indicators: Baird’s tapir and sloths shape forest structure; jaguars and harpy eagles signal intact food webs; the golden frog highlights amphibian vulnerability.

- Wildlife provides clear economic value through ecotourism—birding on Pipeline Road, whale‑watching in Bocas del Toro and turtle‑nest monitoring translate biodiversity into local income.

- Urgent priorities include protecting corridors (Darién–Soberanía links), expanding community conservation programs (e.g., Panama Amphibian Rescue), and supporting marine reserves like Coiba.

- Visit responsibly, support local NGOs and consider joining citizen‑science or volunteer monitoring programs to help safeguard Panama’s wildlife of Panama and the communities that depend on it.