A 19th-century naturalist watching a marsh noticed a tall, silent bird suddenly straighten its long neck and spear a fish in a single, lightning-fast motion — an image that helped define our modern fascination with herons. That scene, embodied today by the Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias), shows how a handful of physical traits and behaviors let these birds thrive along edges of water. Wetlands are under pressure worldwide, so understanding the characteristics of a heron matters for conservation planning: knowing how they feed, nest, and move helps protect the habitats they need. This piece states plainly that herons combine distinct anatomy, feeding strategies, and habitat ties that make them efficient predators and useful indicators of wetland health. Below are ten defining characteristics, grouped into three categories: physical features, behavior and feeding strategies, and habitat, migration, and ecological role.

Physical Features

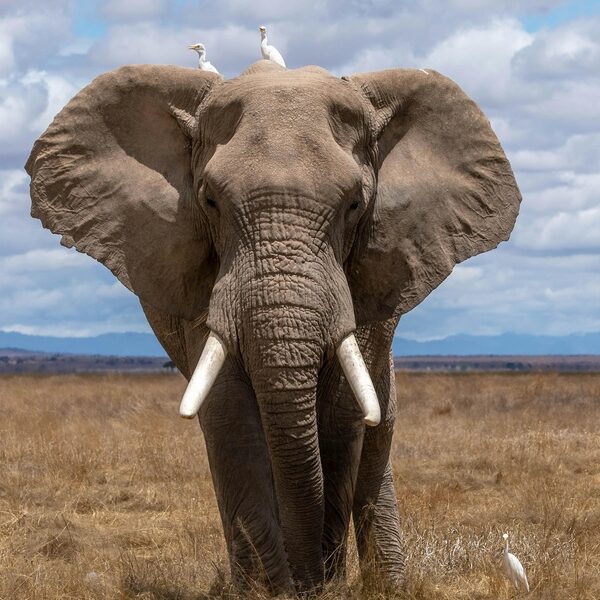

Herons’ physical traits — the long S-shaped neck, dagger-like bill, tall wading legs, and varied plumage — are central to how they hunt and survive along water margins. Measurements and comparisons (Great Blue Heron vs. Grey Heron) illuminate function and scale. Suggested alt text for a category image: “Close-up of a heron’s head and S-shaped neck, showing its dagger-like bill.”

1. Long neck and S-shaped posture

Herons have long, flexible necks that fold into an S-shape, allowing a rapid forward extension during a strike. The neck stores muscular energy and, when released, powers the lightning-fast thrust that impales or seizes prey.

Authoritative field guides and species accounts at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology describe that neck mechanics combine speed and precision in hunting. For scale, an adult Great Blue Heron measures about 97–137 cm in total length with a wingspan commonly 167–201 cm, and stands roughly 1.2–1.4 m tall when upright.

In the field you often see the neck folded close to the body while a heron waits; then, before observers can blink, it unfolds and spears a fish — a marshwatcher’s classic description of a “coil-and-spear” strike.

2. Long, dagger-like bill for spearing and probing

The bill is a heron’s primary tool: long, pointed, and sturdy for stabbing, grasping, and probing. Shape varies by species but the function is consistent — seize slippery fish, probe mud for crustaceans, or snatch frogs and small mammals.

Large species often have bills in the 12–15 cm range (measured from the feather line to the tip), while smaller egrets have proportionally shorter bills. Field guides and accounts from Audubon note that bill morphology correlates with diet breadth: broader diets accompany more generalized bill shapes.

Watch a Great Blue Heron or a Little Egret probe mudflats and you’ll see the bill used both as a spear and as a sensitive probe for hidden prey, demonstrating feeding versatility across habitats from mangroves to urban ponds.

3. Long legs adapted for wading

Herons have long, often scaly legs that let them wade deeply into water to reach prey unavailable to shorter shorebirds. Their long tarsi and toes spread weight on soft substrates, and toes can grip reeds or muddy banks for balance.

Large species like the Great Blue Heron can stand over 1 m tall, allowing them to feed at ankle-to-knee depth or deeper. The leg length and slow, deliberate gait reduce ripples and improve stealth while stalking fish in tidal flats and reedbeds.

Field observers often note a heron’s slow, stalking walk — a strategy that minimizes disturbance and increases prey-capture success in shallow water.

4. Plumage, seasonal colors, and breeding displays

Plumage varies from muted greys to bright whites and often changes seasonally. Many herons develop long breeding plumes, facial ornamentation, or contrasts that are used in courtship displays and to signal species identity.

For example, the Little Egret grows elegant nuptial plumes during the breeding season, while the Grey Heron shows distinguishing facial stripes used to tell similar species apart. In temperate zones breeding plumage and displays typically occur in spring (often March–May).

Plumage also aids camouflage: muted tones help herons blend with reeds and mud while hunting, whereas breeding plumes serve a conspicuous role during courtship.

Behavior and Feeding Strategies

Behavior and feeding strategies are central to heron survival: patient stalking, opportunistic diets, and the dual pattern of solitary foraging with colonial nesting (heronries). Many behaviors draw directly on the neck, bill, and leg adaptations described above. Suggested alt text: “Heron standing motionless in shallow water before striking at a fish.”

5. Patient stalk-and-strike hunting technique

The classic stalk-and-strike method combines long periods of motionless waiting with a rapid forward lunge. Herons will hold still for minutes, watching water movement, then execute a strike typically in under a second.

Observers and field studies summarized by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology report that neck and bill mechanics coordinate to produce that speed and precision, making strikes energetically efficient and highly effective.

In a tidal pool a heron may wait on a rock edge, then launch its neck and bill into a shallow basin and capture a fish before the wave moves — a hunting sequence that conserves energy while maximizing success.

6. Diverse diet and opportunistic feeding

Herons are generalist predators that take a wide range of aquatic and terrestrial prey: fish, amphibians, crustaceans, insects, and even small mammals and birds. Diet composition varies by habitat and season.

Coastal herons often specialize on crabs and small fish, while inland birds feed heavily on frogs and rodents. Urban-adapted Great Blue Herons hunt in stormwater ponds and golf-course lakes, showing how diet flexibility supports persistence in altered landscapes.

By switching prey according to availability, herons maintain feeding success across changing conditions, which helps explain their wide distribution in many wetland types.

7. Solitary foraging but colonial nesting (heronries)

Herons typically feed alone to minimize competition, yet they gather in colonies — called heronries or rookeries — to breed. A heronry is a cluster of nests in trees, reedbeds, or mangroves where multiple pairs nest in proximity.

Clutch size is commonly 3–5 eggs and incubation lasts roughly 25–30 days depending on species, with both parents often sharing incubation and chick-rearing duties. Colonial nesting offers shared vigilance and protection from predators and places nests near productive feeding grounds.

Examples include mixed-species colonies in coastal mangroves and inland rookery trees; conservation groups and local Audubon chapters often monitor these sites for population trends.

Habitat, Migration, and Ecological Role

Herons are tied to water-edge environments, show varied migration strategies depending on latitude, and play key roles as predators and ecosystem indicators. Global distribution examples (Great Blue Heron in the Americas, Grey Heron in Eurasia) highlight both local residency and long-distance movements. Suggested alt text: “A heron standing in a reedbed with water and distant trees.”

8. Preference for wetlands, marshes, and shorelines

>Herons are habitat specialists tied to water-edge environments such as freshwater marshes, estuaries, mangroves, riverbanks, and flooded fields. These habitats supply the foraging opportunities and nesting structures herons need.

Most heron species depend on wetlands for at least part of the year; habitat structure (reedbeds, emergent vegetation, trees) strongly influences local population density. The Great Blue Heron is common along North American coasts and inland wetlands, while the Grey Heron occupies similar niches across Europe and Asia.

Wetland designations by organizations like the Ramsar Convention highlight the global importance of these habitats for waterbirds including herons.

9. Seasonal movement and migration patterns

Migration varies by species and latitude. Temperate populations often migrate in fall and return in spring, while tropical populations may remain resident year-round. Many populations show partial migration: some individuals move while others stay.

For instance, northern Great Blue Herons move south for winter, whereas southern coastal populations remain on territory through the year. Banding studies and summaries from the Cornell Lab document variation in timing and distance linked to temperature and food availability.

Factors such as freeze-over of shallow foraging areas or local prey abundance drive which birds migrate and which remain resident.

10. Ecological role: predator, prey regulator, and ecosystem indicator

Herons are mid-level predators that help regulate fish and amphibian populations and act as bioindicators of wetland health. Because they feed near the top of many aquatic food webs, contaminant accumulation (mercury, PCBs) can reveal environmental pollution levels.

The Ramsar Convention notes that over half of the world’s wetlands have been lost since 1900, a trend that reduces nesting sites and foraging areas for wetland-dependent species. The IUCN assessments show most widespread herons are currently of lower concern, but local declines occur where wetlands are drained or polluted.

Conservation successes — protected estuaries and managed reserves that support stable heronries — demonstrate how targeted wetland protection benefits herons and the wider aquatic community. Understanding the characteristics of a heron therefore directly informs habitat protection and monitoring strategies.

Summary

- Herons pair specialized anatomy (S-shaped neck, long bill and legs, varied plumage) with patient hunting tactics to succeed along water edges.

- They are opportunistic feeders (fish, amphibians, crustaceans, insects, small mammals) and usually forage alone yet nest in colonies with clutches commonly 3–5 eggs and incubation around 25–30 days.

- Herons serve as predators and indicators of wetland health; protecting wetlands under frameworks like Ramsar supports heron populations and broader biodiversity.

- To learn more or take action, visit a nearby wetland or heronry, support local habitat protection, and consult resources such as the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Audubon.