Every year, some migratory birds travel astonishing distances: the Arctic tern averages roughly 71,000 km annually between Arctic breeding grounds and Antarctic feeding areas.

Migration is essential for ecosystem function, but species face mounting threats from habitat loss, climate change, and increasing collision and lighting hazards. Migratory birds share a suite of physical, behavioral, and ecological characteristics that enable seasonal long-distance movement — understanding those traits explains how migration works and why it matters for ecosystems and human activities. For example, the bar-tailed godwit has been recorded flying roughly 11,000 km nonstop (Alaska to New Zealand), a striking anecdote that shows how extreme some migrations can be.

This article uses concrete examples (Arctic tern, bar-tailed godwit, red knot, ruby-throated hummingbird) and authoritative sources (Cornell Lab of Ornithology, BirdLife International, and peer-reviewed studies) to examine eight defining traits organized across four lenses: navigation; physiology and endurance; timing and behavior; and ecology and population dynamics.

Navigation & Orientation

Migratory birds find their way across thousands of kilometers by combining multiple orientation cues so navigation is reliable even when one cue is unavailable. Accurate navigation is foundational: it determines whether individuals reach breeding grounds on time and return to wintering sites safely.

Below we look at two core orientation systems commonly used by migrants: magnetoreception and celestial/solar compasses.

1. Magnetoreception (internal magnetic compass)

Many migratory species detect Earth’s magnetic field and use it as a compass during long flights.

Laboratory and field studies implicate light-sensitive proteins called cryptochromes in the retina (a light‑dependent magnetic sense) and, in some cases, iron‑based receptors (magnetite) elsewhere in the head. Classic experiments show that artificially altering local magnetic fields can change the preferred migratory headings of captive birds (European robin studies in the late 20th century demonstrated predictable reorientation under shifted magnetic fields).

Magnetoreception has applied importance: electromagnetic noise in and around cities can interfere with orientation, and understanding the mechanism helps explain collision patterns and suggests mitigation options. Ongoing research (including work cited by the Cornell Lab) continues to refine how cryptochrome chemistry and magnetite receptors contribute to navigation.

2. Celestial and solar compasses (stars and sun)

Many migrants use the sun by day and stars by night to maintain headings, integrating those cues with an internal clock to compensate for the sun’s movement across the sky.

Mid-20th-century planetarium experiments (Emlen-style orientation trials) showed that night-migrating songbirds orient to star patterns, while controlled photoperiod studies demonstrated how birds calibrate a sun-compass using circadian timing. Observationally, many thrushes and warblers depart at night and appear to time their flights to stable celestial cues.

Light pollution degrades those celestial cues and increases disorientation and collision risk; mitigation approaches include shielding lights, adopting dark-sky policies, and timing lights-down periods during peak migration nights (recommendations supported by BirdLife and other conservation groups).

Physiology & Endurance

Migration demands remarkable physiological shifts: birds build fuel, remodel organs and muscles, and benefit from aerodynamic bodies and wings tuned for their strategy. These adaptations enable nonstop flights of thousands of kilometers in some species and rapid recovery during stopovers.

3. Fat accumulation and metabolic adaptations

Many migrants build large fat reserves before departure and alter metabolism to burn fat efficiently during sustained flight.

Some species increase body mass by roughly 20–40% (or more) before migration. Metabolic changes include higher mitochondrial densities and enzyme shifts that favor fat oxidation. Those changes let small birds like ruby-throated hummingbirds cross the Gulf of Mexico (~800 km) on stored fat, and let larger shorebirds undertake transoceanic legs.

Refueling needs make specific habitats essential: the red knot times its stopover on Delaware Bay to feed on horseshoe crab eggs and can gain many grams per day there. Loss or degradation of such refueling sites has driven measurable population declines, so protecting staging areas is a conservation priority.

4. Wing morphology and flight mechanics

Wing shape and power-to-weight ratios are tailored to migratory strategy — pointed, high-aspect-ratio wings favor sustained, efficient flight, while broader wings favor maneuverability.

Comparative studies link wing aspect ratio and wing loading with migration distance: long-distance migrants (albatrosses, shearwaters) have very long, narrow wings for dynamic soaring, while swifts and swallows have pointed wings for fast, sustained flapping. Wing morphology affects flight speed, altitude, and the number of stopovers required.

Understanding flight mechanics helps manage collision risks (knowing altitude and timing) and explains why some species can sustain oceanic crossings like the Arctic tern (~71,000 km annually) while others rely on frequent short hops.

Timing, Cues & Stopover Behavior

Seasonal timing, environmental cues, and stopover strategies determine when and how birds travel. Precise timing is crucial for arriving when food and breeding conditions peak.

5. Seasonal timing and hormonal control (zugunruhe)

Zugunruhe — migratory restlessness — reflects internal circannual rhythms and hormonal changes that drive migratory readiness.

Photoperiod is a dominant predictive cue; manipulating day length in captive birds shifts their migratory behavior. Hormonal shifts (including changes in corticosterone and reproductive hormones) accompany pre-migratory fueling. Captive songbirds show nocturnal restlessness during migration seasons, a behavioral record of endogenous timing first documented in controlled studies.

Climate-driven phenological shifts have already produced mismatches in some populations where spring arrival no longer coincides with insect or plant food peaks, affecting breeding success (observations summarized by BirdLife and research networks).

6. Stopover ecology and refueling strategies

Stopover sites are essential for replenishing energy reserves; many migrants need multiple stopovers to complete journeys, and refueling rates determine stopover length and survival.

Habitat quality controls how fast birds can refuel—some shorebirds double body mass on rich staging areas. Counts at key sites can reach tens to hundreds of thousands during peak migration, concentrating conservation value. Management actions—protecting wetlands, conserving intertidal beaches, and timing human activities like beach recreation—directly boost refueling success.

Concrete examples include the red knot’s dependence on Delaware Bay horseshoe crab eggs and the large shorebird aggregations in East Asian intertidal wetlands, both of which have documented links between site condition, refueling rate, and population trends.

Ecology, Routes & Social Behavior

Migration also reflects species ecology, defined routes, and social behaviors that influence conservation planning across borders.

7. Species-specific routes and flyways

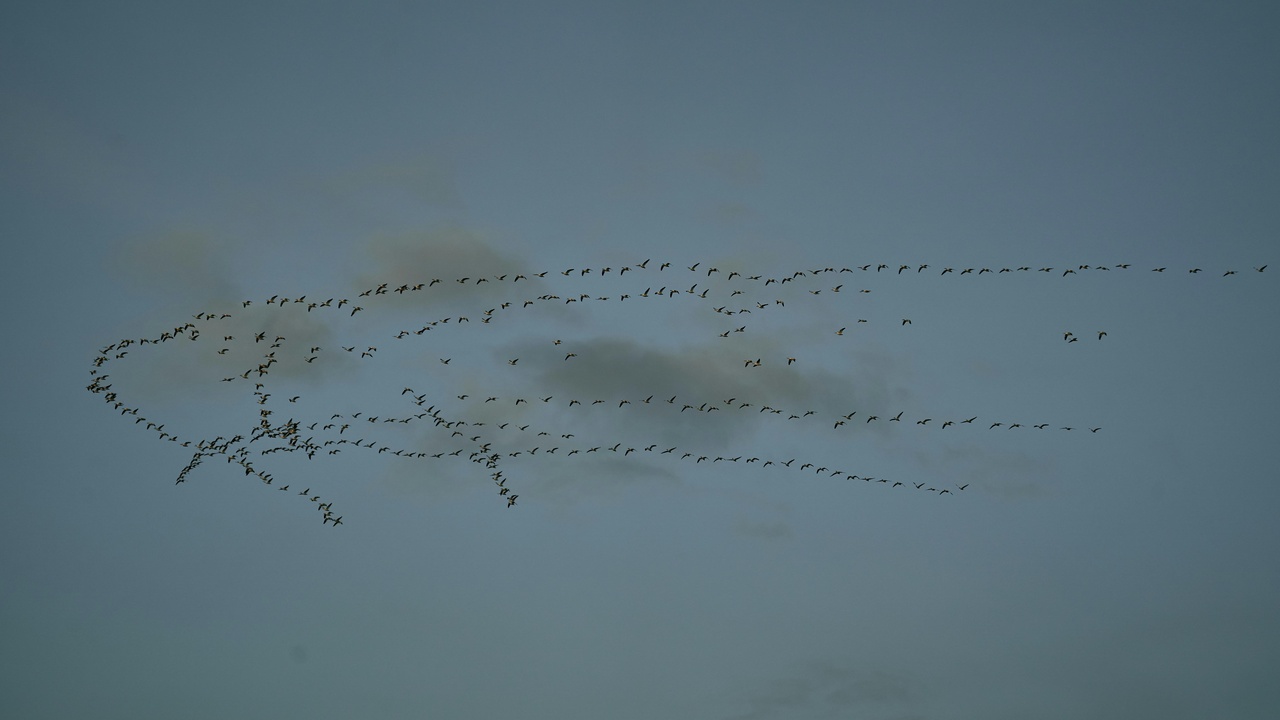

Many migrants follow predictable routes known as flyways that concentrate movements and identify priority habitats.

Major flyways (e.g., East Atlantic, Mississippi, East Asian–Australasian) can carry tens of millions of birds seasonally. Protecting intertidal wetlands and staging sites along a flyway benefits large numbers of species; international cooperation via flyway partnerships and agreements is therefore essential (BirdLife and flyway networks document these needs). About ~1,800 long-distance migratory bird species use intercontinental or significant seasonal movements worldwide, underscoring the scale of conservation coordination required.

The East Asian–Australasian Flyway illustrates how loss of intertidal habitat can shrink populations of shorebirds that rely on a chain of key sites during migration.

8. Social behavior: flocking, leadership, and information transfer

Many migrants travel in groups and use social information for route choice, departure timing, and predator avoidance.

V‑formations in geese reduce individual energy expenditure by a measurable margin (studies estimate modest percentage savings per individual), and young birds often learn routes from experienced adults. Large roosts and dense staging flocks can attract ecotourism but also concentrate disease transmission risk and collision hotspots, which managers must weigh.

Examples include Canada geese flying in V formations and starling or shorebird communal roosts that may number in the tens to hundreds of thousands at peak sites, shaping both conservation opportunity and management challenges.

Summary

Viewed through navigation, physiology, timing, and ecology, eight key traits explain how birds accomplish seasonal long-distance movements and why those movements matter for ecosystems and people.

- Migratory birds rely on multiple navigation systems — magnetic, celestial, and landmark cues — so they can reach distant breeding and wintering sites.

- Physiological adaptations (fat stores, metabolic tuning, organ remodeling) and wing morphology enable endurance flights like the bar-tailed godwit’s ~11,000 km nonstop leg and the Arctic tern’s ~71,000 km annual circuit.

- Timing is controlled by photoperiod and hormones (zugunruhe), and stopover habitats (e.g., Delaware Bay for red knots) are critical for refueling; protecting a few key sites can support many species.

- Flyways concentrate millions of individuals and require international cooperation (East Asian–Australasian and other flyway partnerships); social behaviors like flocking aid navigation but can increase disease or collision risks.

- Practical actions: support local habitat protection and flyway conservation groups, reduce light pollution during migration nights, and consult resources such as the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and BirdLife International for species-specific guidance.