In the mid-20th century, Dutch elm disease wiped out millions of elms from city streets and rural hedgerows, changing how we think about planting durable urban trees.

That loss reshaped neighborhoods and set the stage for later crises — notably the emerald ash borer, first detected in North America in 2002 — which removed tens of millions of ash trees. For homeowners, landscapers, and city foresters, being able to tell an elm from an ash and understanding their different vulnerabilities matters now for canopy planning, pest response, and wood use.

Below are eight clear differences you can use in the field and when making planting or management decisions, with practical ID tips, pest histories, and real-world recommendations for replacement and maintenance (comparing elm and ash trees throughout).

Physical differences and identification

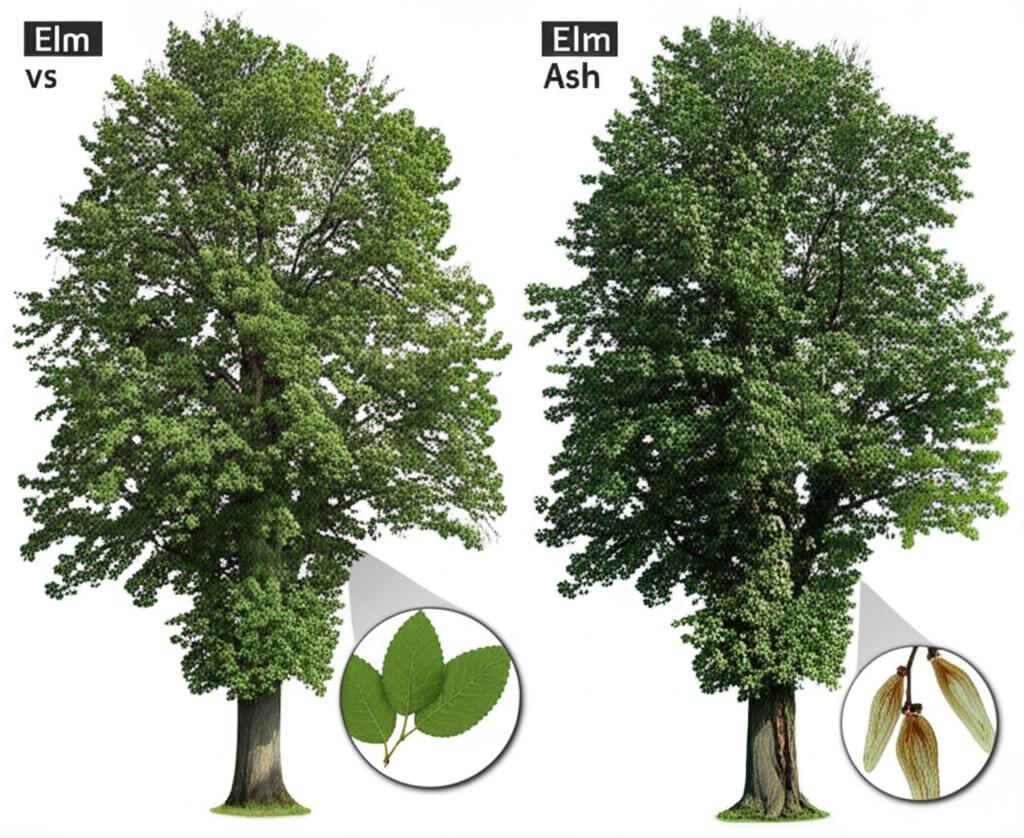

Arborists rely on leaves, twig/bud arrangement, and seeds or flowers to separate elms and ashes year-round. These characters are easy to check and remain diagnostic whether the tree has foliage or not.

1. Leaf shape and arrangement

Elms have single, simple leaves arranged alternately along the twig; ashes have pinnate compound leaves with leaflets arranged opposite each other. That contrast is one of the quickest summer checks.

American elm (Ulmus americana) leaves are typically 5–12 cm long, toothed, and often show an asymmetrical base where the two sides of the leaf blade meet the petiole unevenly. By contrast, green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica) usually bears 5–11 leaflets per compound leaf; individual leaflets commonly run 3–12 cm long and sit opposite along the rachis.

Field tip: if you see a single leaf on a stem, it’s likely an elm; if you see a multi-leaflet cluster with opposite placement, it’s an ash. Note that some elm cultivars have smaller or slightly variable leaves, so use multiple traits when in doubt.

2. Buds, twigs, and bark texture

Branching and bud arrangement are excellent winter ID features: ashes branch and bud opposite, while elms branch and bud alternately.

Ash twigs bear stout, opposite buds often 4–8 mm long; mature Fraxinus bark typically develops a tight diamond pattern with intersecting ridges. Elm twigs have smaller lateral buds (often under 4 mm) and alternate placement; older Ulmus bark becomes coarse and deeply furrowed with irregular ridges rather than the regular diamond check of ash.

Visual cue: run your hand up a twig and look at how buds pair up. Opposite pairs = ash; single alternating buds = elm. Mature American elm bark examples show deep furrows and flaky ridges, while green ash bark displays the classic diamond texture.

3. Flowers and seed types

Both genera produce winged seeds, but the form and timing differ in ways that help identification and explain dispersal strategies.

Elm seeds are small, often clustered, and enclosed in a thin, papery membrane (resembling tiny round samaras) that typically disperse in spring after flowering. Ash produces single-seeded samaras — the familiar “keys” — attached singly or in loose clusters; in some Fraxinus species the keys persist into winter on the tree, making ash identifiable through colder months.

Practical note: nurseries propagate both from seed or nursery stock, but seed timing matters — many temperate elms and ashes flower and shed seed in spring, so plan collection accordingly (spring seed flush for most species).

Ecology, pests, and disease susceptibility

Elms and ashes both face serious pest and disease threats, yet the agents, timelines, and management options vary. Understanding those contrasts helps guide sanitation, treatment, and replanting choices.

4. Disease vulnerabilities and historical impacts

Elms were devastated by Dutch elm disease, a fungal pathogen spread by bark beetles; major outbreaks peaked in the 1950s–1960s and removed whole street-tree cohorts across North America and Europe. The visual and cultural loss was enormous: avenues once lined with American elm disappeared within decades.

Ashes have suffered a different fate. The emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis) was first detected in North America in 2002 (near Detroit) and is associated with the loss of tens of millions of ash trees across the continent. In Europe, Fraxinus species face ash dieback (Hymenoscyphus fraxineus), a fungal disease that has caused major declines there as well.

The agents differ — beetle-vectored fungus for elms versus an invasive wood-boring beetle (and additional fungal threats to ash) — and so do the timelines and policy responses led by agencies such as USDA APHIS and state extension services.

5. Pest threats and practical management

Pest risk changes the management toolkit. For elms, emphasis is on sanitation pruning, removing infected material, monitoring for elm bark beetles, and planting DED-resistant cultivars where available.

Ash management centers on systemic insecticides (injectable or soil-applied) to protect valuable trees from EAB and, increasingly, biological controls such as introduced parasitoids. Typical protection schedules recommend systemic treatments every 2–3 years for ongoing EAB pressure, though municipal programs vary by budget and tree value.

Practical homeowner guidance: confirm diagnosis before treating, consult local extension, and weigh long-term costs — city programs often treat high-value street trees while homeowners may choose removal and replacement for smaller specimens. Some cities run cost-per-tree programs; treatment can range from a few hundred dollars over several years to thousands for large specimens.

6. Wildlife interactions and ecosystem roles

Each genus supports different parts of the local food web. Historically, elms provided dense shade, strong branching for cavity nesters, and abundant spring seed clusters that fed insects and birds.

Ash trees offer samaras and foliage used by seed-eating birds and small mammals and support dozens of insect species locally (exact counts vary by region). Losses of either genus reduce canopy cover and alter habitat structure — for example, mature elm-lined streets once sheltered cavity-nesting species that decline when large trees vanish.

When planning replacements, consider species that restore structural diversity and food resources; losing hundreds of the same kind of tree in a neighborhood can disproportionately harm urban biodiversity.

Uses, wood properties, and urban planning

Wood characteristics and pest risk both shape how craftsmen and cities use these trees. Below are practical differences in timber use and in how municipalities now choose between them — including a note on elm vs ash trees in modern planting lists.

7. Timber and wood uses

Ash wood is prized for strength, straight grain, and shock resistance, which makes it a traditional choice for tool handles, furniture, and sporting goods. For decades, manufacturers such as Louisville Slugger historically used ash for many baseball bats because of its combination of strength and flex (though maple and other species are common alternatives today).

Elm has an interlocked grain that resists splitting and swells predictably when worked; that made it useful for furniture, veneers, cooperage, and older wheel hubs or barrel staves. The look of elm grain is distinctive, and antique elm pieces are prized for that reason.

Pest-driven declines influence availability and price: when large quantities of ash or elm are lost to insects or disease, supply tightens and mills shift to other species, which can raise costs for specialty wood users and shorten traditional supply chains.

8. Urban landscaping and management choices

Ash was long favored for fast growth and urban tolerance, but widespread EAB presence means many municipalities now avoid planting untreated Fraxinus unless part of a managed, treated program. Conversely, disease-resistant elm cultivars like ‘Princeton’ and others have returned elms to planting lists where Dutch elm disease pressure is managed.

Practical recommendations: diversify species in planting plans (aim for no more than 10% of street trees from a single species or genus), consult local extension for current pest advisories, and consider resistant cultivars when restoring historic avenue plantings. Budget for maintenance and potential treatments over decades rather than a single season.

Municipal examples: several cities revised planting lists after EAB, moving away from heavy Fraxinus representation and adding mixes of oaks, maples, and native alternatives to reduce future canopy loss.

Summary

- Look first at leaves and branching: simple alternate leaves and alternate buds point to elm; opposite, pinnate leaves and opposite buds point to ash.

- Historic pest patterns differ — Dutch elm disease reshaped mid-20th-century streets, while emerald ash borer (detected in 2002) has killed tens of millions of ash — so management and prevention strategies are not interchangeable.

- Wood uses vary: ash is prized for strength and shock resistance (tool handles, bats), elm for interlocked grain and specialty furniture; pest losses change availability and market choices.

- Actionable steps: diversify plantings (keep any single genus under ~10% of the canopy), favor resistant cultivars such as ‘Princeton’ for elm restoration, and contact your local extension or forestry office for current treatment or quarantine guidance on elm vs ash trees.