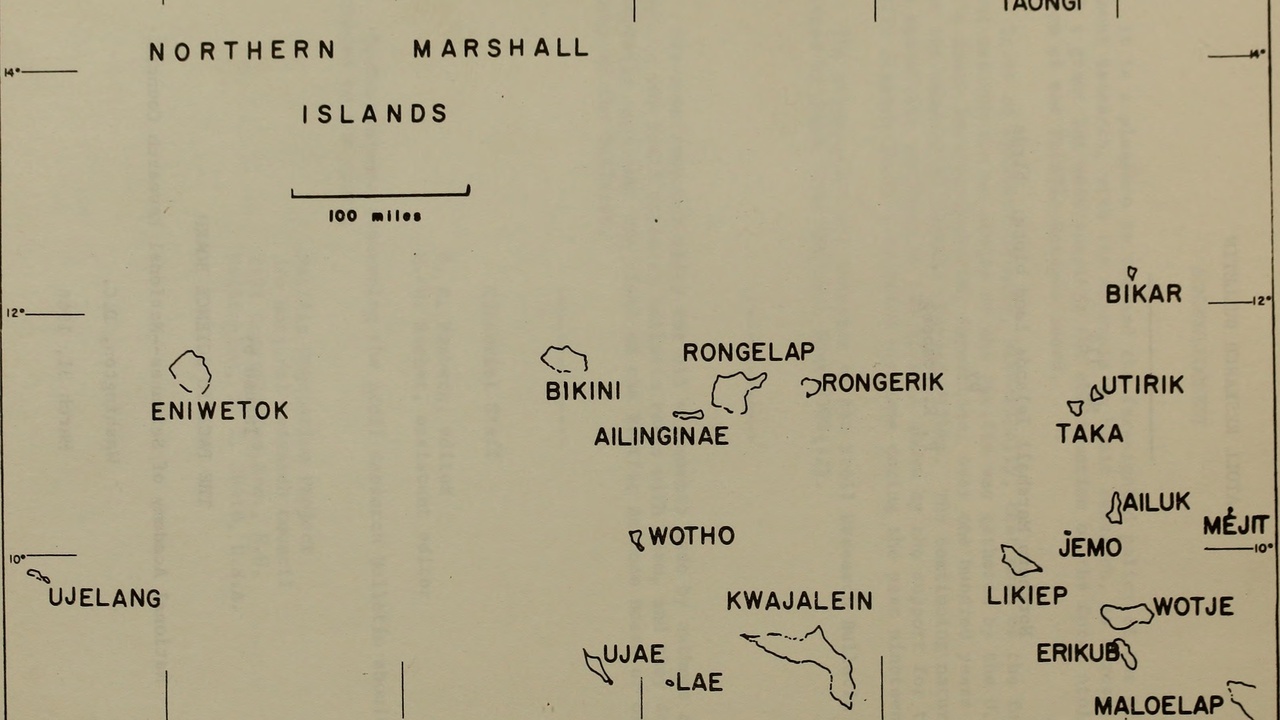

When the United States conducted nuclear tests at Bikini and Enewetak Atolls between 1946 and 1958, scientists from around the world descended on the atolls to study unexpected ecological responses. That moment in history left a complicated legacy, but it also focused attention on how resilient—and how fragile—the islands’ plants and animals can be. The Republic of the Marshall Islands is made up of 29 atolls and 5 single islands, yet it controls an ocean territory (an EEZ) of roughly 2.1 million km², which helps explain why a small land area supports rich marine life. Despite geopolitical upheaval and rising climate threats, the Marshall Islands harbor a surprising diversity of tropical wildlife — from endangered sea turtles to seabirds and reef giants — each playing a vital role in coral-atoll ecosystems and local culture. Readers should care because these species underpin fisheries, protect shorelines, and carry deep cultural meaning. Suggested sources for species status or historical context include IUCN, NOAA, and Marshall Islands conservation organizations. This article highlights seven notable tropical wildlife species/groups from the Marshall Islands.

Marine megafauna and coastal species

Large marine and coastal animals—sea turtles, rays, and dolphins—link atoll reefs, lagoons, and the people who live on them. Their movements move nutrients between deep ocean and coral flats, and their feeding habits shape reef structure. Herbivorous turtles and fish keep algae in check; manta rays may concentrate nutrients around cleaning stations; dolphins signal healthy food webs.

These animals also hold cultural and subsistence value for Marshallese communities, appearing in stories and local diets when permitted. Major threats include overfishing and destructive gear, warming-driven habitat loss for nesting or foraging, and lingering contamination concerns in areas affected by past testing. Regional conservation data—IUCN listings for turtles, NOAA reports on manta aggregations, and community monitoring programs—help guide protection and community-led management.

1. Green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas)

The green sea turtle is a frequent nester and lagoon feeder across many Marshall Islands atolls. IUCN lists Chelonia mydas as Endangered, and seasonal nesting and foraging sites in the Marshalls are locally important for regional recovery efforts.

Community nest-monitoring programs record hundreds of emergences on some atolls in calmer years, and traditional stewardship has long helped protect eggs and hatchlings. Green turtles graze on seagrass and algae, which helps prevent algal overgrowth that can smother coral.

Practical benefits include eco-tourism opportunities and cultural practices that support conservation when harvest is restricted. Major threats remain illegal take, bycatch in nearshore fisheries, and nest inundation from sea-level rise. For status and guidance, see IUCN assessments and local turtle-monitoring groups.

2. Hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata)

Hawksbill turtles are closely tied to coral reef habitats and were historically targeted for their tortoiseshell. The species is listed as Critically Endangered by IUCN, and international trade has been restricted under CITES since the late 20th century.

Hawksbills rely on reef complexity to find sponges and other food; reef degradation therefore hits them hard. Protecting reef habitat benefits hawksbills, local fisheries, and tourism simultaneously.

Conservation actions include anti-poaching patrols, CITES enforcement, and reef restoration that improves foraging habitat. Citing IUCN and CITES reports helps frame protection priorities for this species.

3. Spinner dolphin and reef sharks (common coastal cetaceans and sharks)

Spinner dolphins regularly use lagoonal waters for feeding and socializing, while reef sharks such as gray reef sharks patrol passes and drop-offs. Both groups assist nutrient exchange between habitats and are important parts of local food webs.

Fishermen and researchers commonly report sightings around passes and outer reefs, and these animals support low-impact wildlife tourism like dolphin watching and guided shark-viewing trips. Their presence often signals healthy prey populations.

Management needs include protecting key passages with marine protected areas, reducing bycatch, and enforcing sustainable fisheries. Regional survey data (NOAA and Micronesian studies) provide baseline sighting rates and help target MPA placement.

Seabirds and shorebirds

Seabird colonies—terns, noddies, and frigatebirds—transport ocean nutrients to tiny islets, enriching soils and sustaining coastal vegetation. Their guano fertilizes trees and shrubs, which in turn stabilizes sand and provides habitat for other species.

Many of these species are migratory and breed seasonally; some colonies number in the hundreds to thousands according to regional surveys. Major threats include invasive rats that eat eggs and chicks, and low-lying nesting sites that are vulnerable to sea-level rise and storm surge. BirdLife International and regional monitoring programs track colony trends and prioritize predator control.

4. Great frigatebird (Fregata minor)

The great frigatebird is a large seabird often seen soaring above atoll lagoons and reef passes. It nests on treeless islets and relies on offshore feeding grounds for sustenance.

Frigatebirds act as scavengers and inadvertent nutrient carriers; nesting colonies concentrate guano that enriches island soils. They also feature in local knowledge and are notable in aerial displays during breeding seasons.

Threats include egg and chick predation by invasive mammals and loss of small nesting islets to inundation. BirdLife International provides range and status notes useful for conservation planning.

5. Sooty tern and noddies (Sterna fuscata and Anous spp.)

Sooty terns and noddies form dense breeding colonies on low-lying islets and are among the most numerous seabirds across the atolls. Regional counts record colony sizes from the hundreds into the thousands on suitable islets.

These colonies deliver large pulses of marine-derived nutrients that support vegetation and seabird-dependent food webs. When storms or sea-level rise wash over nesting islets, entire colonies can be lost, affecting wider ecosystem productivity.

Protecting remote nesting sites, eradicating invasive rats, and maintaining island vegetation are practical conservation steps reported by regional seabird surveys and national reports.

Coral reef species and invertebrates

The coral reefs surrounding Marshallese atolls host diverse reef fish, invertebrates, and corals that form the foundation of nearshore ecosystems. These species provide food security, protect shorelines by absorbing wave energy, and sustain livelihoods through fisheries and tourism.

Reefs here have felt the effects of global bleaching events (notably 2016–2017), and continued warming, acidification, overfishing, and destructive gear threaten recovery. NOAA reef monitoring and regional studies document bleaching impacts and guide restoration and management actions.

Maintaining herbivore populations and supporting coral recruitment are central to resilience efforts across the atolls.

6. Giant clams (Tridacna spp.)

Giant clams (Tridacna spp.) are conspicuous reef invertebrates that add to reef carbonate budgets and provide protein to island communities in some places. Several Tridacna species are monitored regionally and are subject to protections to prevent overharvest.

Conservation projects in Micronesia and the wider Pacific have re-planted juvenile clams onto reefs to boost biodiversity and local food sources. Clams also host symbiotic algae that help reef productivity, making them useful in restoration work.

Threats include collection for meat and shells, bleaching, and disease. NOAA and regional marine programs document clam health and coordinate replanting and regulation enforcement.

7. Parrotfish, surgeonfish and reef fish communities

Herbivorous reef fishes such as parrotfish and surgeonfish form the backbone of reef health; their grazing prevents algal dominance and facilitates coral recruitment after disturbance. More broadly, reef fish communities support local fisheries that supply household protein on many atolls.

Studies in Pacific atolls suggest reef fisheries supply a substantial share of protein for coastal households, and declines in herbivores are often linked with reduced coral recovery. Management tools—size limits, gear restrictions, and community closures—have shown positive results in Micronesia.

Adaptive local fisheries management, backed by regional data from NOAA and FAO, is key to balancing food security and reef resilience.

Summary

- Seven standout groups—from endangered green and hawksbill turtles to seabird colonies and reef engineers like giant clams—sustain atoll ecosystems and local ways of life.

- Reefs, megafauna, and seabirds deliver essential ecosystem services: shoreline protection, nutrient cycling, and food security across an EEZ of roughly 2.1 million km².

- Major threats include overfishing, invasive species (rats), coral bleaching (e.g., 2016–2017 events), and sea-level rise; international and regional tools (IUCN, CITES, NOAA, BirdLife) inform priorities.

- Community-based monitoring and management—nest patrols, MPA placement, fisheries rules, and island predator control—are practical, proven actions that aid recovery.

- To support protection of the wildlife of the Marshall Islands, consider donating to or amplifying local NGOs, consulting IUCN/NOAA/UNESCO resources, and learning about sustainable seafood and marine stewardship.