Why do backyard birders call the orange-breasted American robin a “robin” while the European robin — much smaller and unrelated — gets the same common name? That naming quirk hints at deeper differences.

That question matters for anyone trying to identify birds, submit clean records to platforms like eBird, or simply understand basic natural history. Common names can obscure relationships, so learning clear, measurable contrasts helps both casual observers and citizen scientists report accurately.

This piece lays out six straightforward differences between robins and the wider group called true thrushes—covering appearance, song, behavior, taxonomy, range, and conservation—using examples and authoritative sources like the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Audubon, and the IUCN.

Appearance and Plumage

Visual ID is the most immediate way birders separate species in the field. Plumage and measurable size/shape differences provide quick, reliable clues, though variations by age and season mean examples matter.

1. Size and Body Shape

Robins, depending on which species you mean, are often stockier or larger than many small thrushes, but the common name spans sizes. For instance, the American robin (Turdus migratorius) typically measures about 23–28 cm in length and weighs roughly 77–85 g (adult ranges cited by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology).

By contrast, the European robin (Erithacus rubecula) is only about 12.5–14 cm long—a useful reminder that “robin” is a vernacular label, not a size class. Many Turdus thrushes (e.g., song thrush, Turdus philomelos) fall in the 20–28 cm range, so bill shape, tail length and upright vs hunched posture often help separate an American robin from a similarly sized thrush in a backyard.

2. Plumage and Color Patterns

Plumage is where most people expect the biggest contrast: the American robin has an orange-red breast with a gray-brown back, while many thrushes show heavy dark spotting or streaking on pale underparts.

Examples: song thrush (Turdus philomelos) has brown upperparts and dense, arrow-shaped spots on a cream breast; hermit thrush (Catharus guttatus) shows a subtly reddish tail with clear, round spotting below. Juveniles of both groups can be heavily spotted; molts typically occur in late summer, which changes field appearance heading into fall and winter.

Behavior and Vocalizations

When visuals fail—dawn chorus or dense woods—behavior and voice are the next-best identifiers. Song structure, call notes, and foraging style often separate robins from many thrush species and tell you where to look for them.

3. Song and Calls

Thrushes frequently sing complex, flute-like phrases with clear harmonic overtones; the hermit thrush is a classic example described by the Cornell Lab as “ethereal” and richly harmonic. Those notes often form variable sequences rather than tight repetitions.

By comparison, the American robin’s song tends to be a more direct series of short, repeated phrases—think of the familiar “cheer-up, cheerily” motifs. Sonogram analyses show thrush notes carry distinct harmonic structure; typical phrase lengths for many thrush notes fall in the 2–4 second range, which helps separate an unseen singer at dawn.

4. Foraging Behavior and Diet

Feeding style is another clear divider: American robins often forage on open turf, pulling earthworms and probing soil with an upright stance. Observers commonly see robins tugging multiple worms in quick succession during spring mornings.

Many thrushes, meanwhile, flip and probe leaf litter, glean insects from low vegetation, or switch to a berry-heavy diet during migration and winter. Swainson’s thrush and hermit thrush often favor fruit on shrubs during migration, and song thrushes are known to use “anvil” rocks to break snail shells—an ingenious, species-specific foraging tactic.

Taxonomy, Range, and Conservation

Common names like “robin” can mask taxonomic reality: some birds called robins are true thrushes, others belong elsewhere. Taxonomy shapes how scientists track species, set conservation priorities, and interpret distribution and migration differences.

5. Taxonomic Relationships and Naming

The American robin is a true thrush: Turdus migratorius, in family Turdidae (see authorities like the IOC/Clements and the Cornell Lab). Other “robins” are not close relatives—Erithacus rubecula, the European robin, belongs to a different Old World group (commonly placed among the Old World flycatchers, Muscicapidae, in modern checklists).

Early European settlers often applied familiar names to unfamiliar New World birds, which explains why unrelated species share the “robin” label. The takeaway: a shared common name doesn’t guarantee close evolutionary ties.

6. Habitat, Migration and Conservation Status

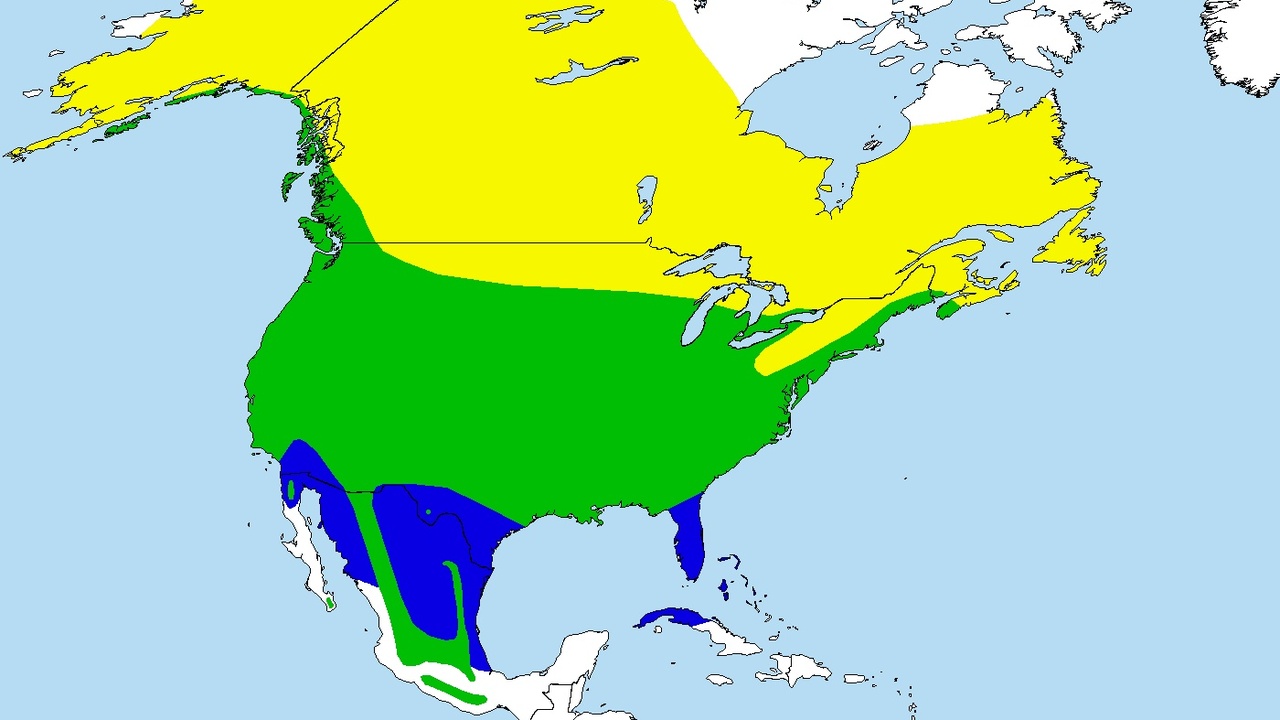

Range and migration patterns have practical implications for observers and conservationists. The American robin is widespread across North America, common in urban and suburban habitats, and listed as IUCN Least Concern.

By contrast, many thrushes are forest breeders and long-distance migrants: Swainson’s thrush (Catharus ustulatus) travels between boreal North America and Neotropical wintering grounds—journeys of thousands of kilometers. Some relatives face greater risk; for example, Bicknell’s thrush (Catharus bicknelli) has a more restricted high-elevation breeding range and is listed as Near Threatened by the IUCN.

Habitat preference (lawns and yards vs forest understory) affects which birds you’ll see locally, and reporting sightings to platforms like eBird helps track population changes across seasons.

Summary

- Visual clues: size, bill shape and underpart patterns (orange breast vs spotted breast) are often the first, fastest ID tools.

- Vocal differences: thrushes often sing flute-like, harmonic phrases; the American robin uses shorter, repeated phrases.

- Behavioral cues: robins favor turf and earthworms; many thrushes flip leaf litter or switch to berries during migration.

- Taxonomy and naming: American robin (Turdus migratorius) is a true thrush, while other “robins” (e.g., Erithacus rubecula) are not closely related.

- Range and conservation: some thrushes are long-distance migrants or habitat specialists (e.g., Swainson’s thrush, Bicknell’s thrush) and merit focused monitoring; log your sightings on eBird and consult Cornell Lab or Audubon for local guidance.