In the late 19th century, naturalists traveling Sweden’s forests and fjords catalogued species that today define northern Europe—animals adapted to long winters, vast forests, and rugged coasts.

That work still matters. Swedish wildlife supports timber and game economies, sustains fisheries and tourism, and helps regulate pests and nutrients across landscapes where roughly 70% of the land is forested. This piece highlights 10 representative Nordic animals found across habitats from Lapland tundra to the Baltic shore, and for each I cover identification, population and conservation notes, ecological roles, and human interactions like hunting, tourism, and stewardship. The fauna of Sweden is varied, surprising, and closely tied to local cultures.

Large Mammals of Sweden

Sweden hosts several large, charismatic mammals that shape forest structure and local culture. These species influence timber dynamics through browsing, support hunting economies via licensed seasons, and draw wildlife watchers—moose-watching in Värmland is a notable example. Population monitoring and regulated harvests are central: authorities use aerial surveys, genetic sampling, and hunter reporting to set quotas and reduce conflicts.

Human-wildlife interactions are frequent and measurable—moose–vehicle collisions number in the thousands each year, and licensed hunts harvest tens of thousands of animals annually—so management balances ecological goals with public safety and livelihoods. Programs such as bear monitoring by Naturvårdsverket and Sami reindeer husbandry show how conservation and culture intersect in Sweden.

1. Moose (Alces alces) — Sweden’s Iconic Forest Giant

The moose is unmistakable: a huge, long-legged deer with broad palmate antlers on males, favoring mixed forests, wetlands, and roadside browse. Sweden’s population is commonly estimated at roughly 300,000–400,000 animals, with regional fluctuations driven by winters and hunting pressure.

Management is intensive: annual licensed hunts remove a substantial portion of the population (around 80,000 are harvested in a typical recent season), and collisions with vehicles are a persistent issue—several thousand crashes happen each year, with local peaks in forested regions. Moose affect forestry through browsing and can shape regeneration patterns.

Moose are also a tourism draw; guided moose-watching tours around Värmland and Dalarna are popular in autumn and spring. Population surveys, hunter licensing, and traffic mitigation (signing and fencing) are routine parts of moose management.

2. Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) — Semi-domesticated Lifeline of Lapland

Many reindeer in Sweden are semi-domesticated and central to Sami life. Adults have slender faces, a compact build, and both sexes can carry antlers; herds move seasonally between coastal lowlands and mountain pastures.

There are roughly 200,000–250,000 semi-domesticated reindeer across northern Sweden, managed by Sami owners under a regulated husbandry system. Herding supports livelihoods, cultural traditions, and seasonal events like rounding-up and calf-marking.

Contemporary challenges include competing land uses—forestry, mining, and wind farms can fragment grazing areas—and legal protections aim to safeguard both the industry and Sami cultural rights. Traditional migrations and veterinary programs remain vital to herding resilience.

3. Brown Bear (Ursus arctos) — Recovering Predator of the North

Brown bears occur mainly in northern and central Sweden, occupying dense forest and mountain edge habitats. Adults are large, shaggy, and omnivorous, with a recovery story over recent decades.

Populations have rebounded since protections enacted in the mid-20th century and are now commonly estimated at roughly 2,500–3,500 individuals (varies by monitoring year). Recovery accelerated from the 1970s through the 1990s with habitat protection and reduced persecution.

Bears are the focus of ecotourism (guided hide-based viewing in places such as Dalarna and Småland), research using DNA and telemetry, and regulated hunting quotas in some regions. Naturvårdsverket coordinates monitoring and safety outreach to reduce negative encounters.

Birds That Define Sweden’s Skies and Wetlands

Birds are essential to Sweden’s ecosystems: they connect habitats along migratory flyways, cycle nutrients in wetlands, and figure prominently in folklore and tourism. The country hosts well over 300 migratory and wintering species that pass through or breed here each year, making stopover sites like Skåne, Öland, and Hornborgasjön critically important.

Conservation concerns focus on ground-nesters and forest specialists sensitive to fragmentation and disturbance. Protected wetlands and old-growth patches, alongside hunting regulations, help maintain breeding populations and the recreational birdwatching economy.

4. Whooper Swan (Cygnus cygnus) — A Migratory Wetland Specialist

The whooper swan is a large, white waterbird with a long neck and distinctive yellow-and-black bill. It breeds in northern wetlands and tundra and winters in southern Sweden and continental Europe.

Key staging sites such as Hornborgasjön see thousands gather in spring during migration; many swans arrive in March–April and depart in October–November depending on weather. Regional counts and festivals around spring congregations draw birdwatchers and help fund wetland restoration.

Conservation measures that protect shallow wetlands—dike management, grazing regimes, and water-level control—benefit swans and other waterbirds, and local monitoring shows generally stable to improving trends where habitats are restored.

5. Capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus) — Specialist of Old-forest Landscapes

The capercaillie is a large grouse linked to mature conifer forests with a structured understorey. Males display at lek sites in spring with a loud wing-beating courtship that’s unmistakable to forest visitors.

Populations have fragmented as forestry practices simplify stands or remove key lek and brood habitats. Studies across regions document local declines, prompting management responses like habitat corridors, retention of old trees, and regulated hunting in sensitive zones.

Conservation efforts focus on maintaining a mosaic of mature stands, protecting lek sites, and coordinating forestry planning with wildlife agencies to balance timber production and biodiversity.

6. Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) — Apex Bird of Prey

Golden eagles inhabit mountainous and open forested areas in northern Sweden, notable for broad wingspans and powerful flight. Pairs defend large territories and nest on cliff ledges or tall trees.

The species is protected, and regional monitoring provides territory density estimates used to guide disturbance limits. While rare instances of livestock conflict occur in remote areas, most interactions are positive—eagles are a draw for wildlife enthusiasts and researchers tracking nesting success and migration.

Local bird observatories and conservation groups monitor nests and publicize viewing guidelines to reduce disturbance at known breeding sites in the northern mountain ranges.

Carnivores and Small Mammals of the Nordic North

Sweden hosts recovering large carnivores and specialized arctic small mammals that play critical roles in predator-prey dynamics and indicate ecosystem health. Conservation programs include reintroductions, protected core zones, and targeted research to understand distribution and threats.

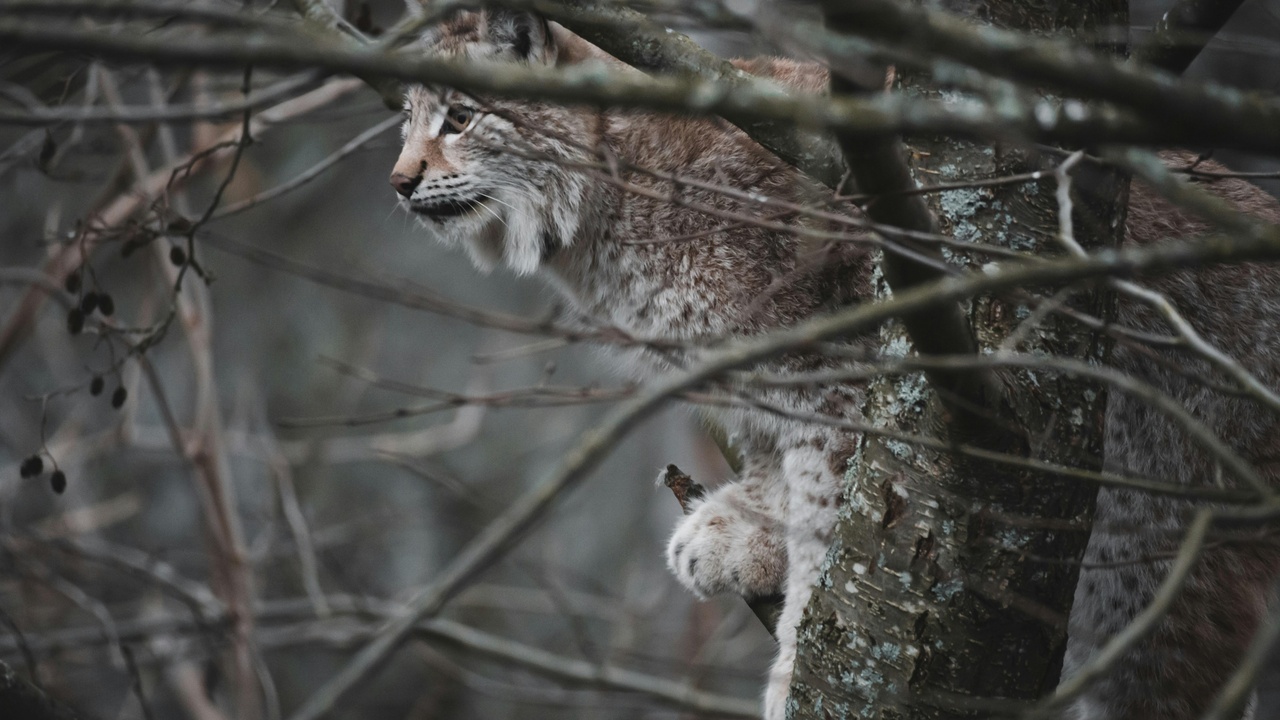

Balancing land use with predator conservation is a recurring challenge: for example, the Eurasian lynx is often estimated at about 1,000–2,000 individuals nationally, and monitoring informs licensed management, conflict mitigation, and farmer compensation schemes.

7. Eurasian Lynx (Lynx lynx) — Elusive Forest Predator

The Eurasian lynx is a solitary, secretive cat of mature forests with tufted ears and a short tail. It preys mainly on deer and smaller mammals, helping regulate ungulate densities and vegetation impacts.

Population estimates typically range between about 1,000 and 2,000 individuals in Sweden, based on telemetry, camera traps, and genetic sampling. Threats include poaching and habitat fragmentation, while some regions use licensed harvest and targeted deterrence to reduce livestock losses.

Telemetry studies and regional coexistence programs with landowners aim to reduce conflict and maintain lynx as a functional part of forest ecosystems.

8. Arctic Fox (Vulpes lagopus) — Specialist of Mountain Tundra

The arctic fox occupies high-altitude tundra and rocky fell environments, adapted to cold with seasonal coat changes and compact bodies. It relies on small rodents and seabird colonies where available.

Populations are small and locally vulnerable; in parts of Sweden they reached critically low numbers late in the 20th century. Conservation measures include captive breeding, careful release programs in the Scandinavian Mountains, and protected tundra habitats to reduce competition from the expanding red fox.

Action programs in areas such as Fulufjället and Sápmi combine monitoring, anti-poaching work, and habitat protection to give the arctic fox a better chance as the climate and species distributions shift.

Marine and Freshwater Species of Sweden’s Coasts and Rivers

Sweden’s long coastline, archipelagos, and many rivers support rich marine and anadromous life that underpins fisheries, recreation, and coastal cultures. These systems provide services like fish production and nutrient cycling but face threats from dams, pollution, and overfishing.

Conservation responses include marine reserves, fish passages and ladders to restore migration routes, and monitoring of contaminants. With coastal economies dependent on healthy stocks, restoration projects—such as salmon river rehabilitation—have measurable social and ecological payoffs.

Altogether, the fauna of Sweden’s coasts and rivers connects inland and marine food webs and remains a high priority for agencies and local communities working to restore runs, reduce bycatch, and sustain fisheries for tomorrow.

9. Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) — River Migrant and Conservation Priority

Atlantic salmon are anadromous: born in rivers, they migrate to sea to grow and return to spawn. Historically abundant, many Swedish runs declined steeply in the mid-20th century due to damming, pollution, and overfishing.

Restoration work—fish ladders, river habitat restoration, and hatchery and monitoring support—has reopened some systems; several rivers have seen notable recoveries after interventions. In some impacted rivers declines of up to 80% were recorded since the 1950s, which spurred the restoration push.

Salmon restoration benefits recreational and commercial fisheries, boosts local economies, and restores ecological connectivity; projects on rivers such as the Göta älv illustrate coordinated engineering and community monitoring efforts.

10. Grey Seal (Halichoerus grypus) — Coastal Top Predator

Grey seals haul out on rocky islets and beaches around Sweden’s west coast and in parts of the Baltic, where they breed, rest, and thermoregulate. Adults are large, with robust bodies and distinctive long noses.

After historic hunting restrictions, many grey seal populations have increased in recent decades. This recovery has led to occasional conflicts with fisheries, but also to growing seal-watching tourism and increased research into disease and contaminant loads.

Important colonies occur around Kosterhavet and the Skagerrak coast; marine institutes monitor numbers, health, and ecosystem impacts while managers trial measures to reduce gear losses and promote coexistence.

Summary

- Sweden’s fauna spans iconic large mammals, migratory birds, specialized arctic species, and coastal and riverine life—each group shaping ecosystems and local economies.

- Many populations have recovered thanks to protections, monitoring, and targeted programs, but modern threats like climate change, habitat fragmentation, and competing land uses remain pressing.

- Cultural and economic values overlap: Sami reindeer husbandry, moose and game hunting, salmon fisheries, and wildlife tourism all depend on healthy populations and smart management.

- Practical ways to engage include supporting Naturvårdsverket and local conservation NGOs, practicing responsible wildlife watching, and joining citizen science counts or local river-restoration efforts.